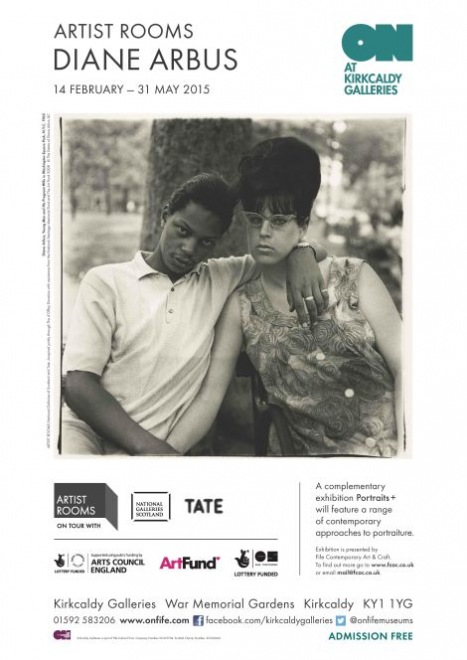

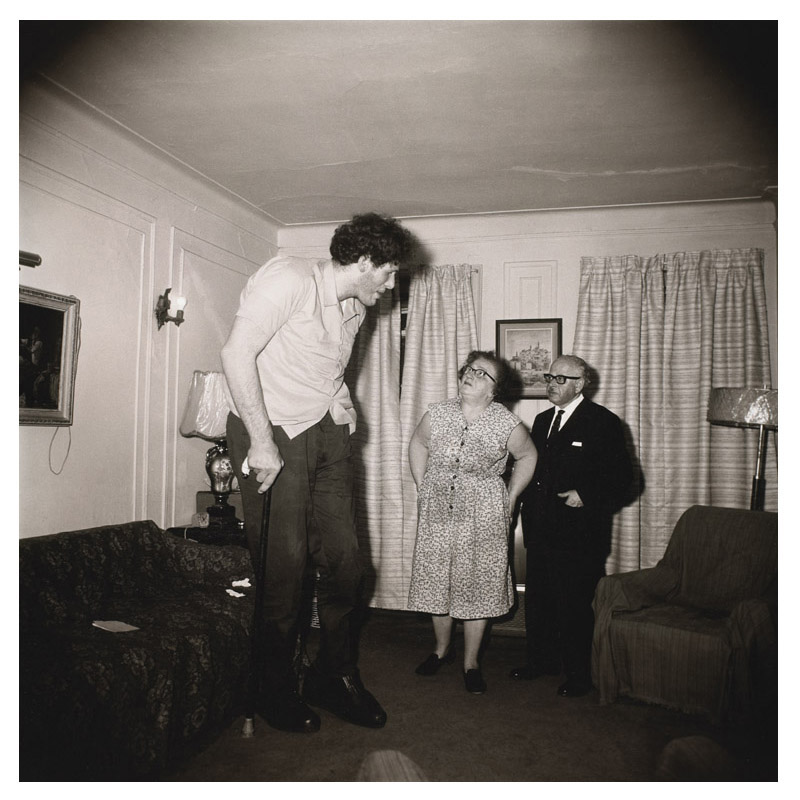

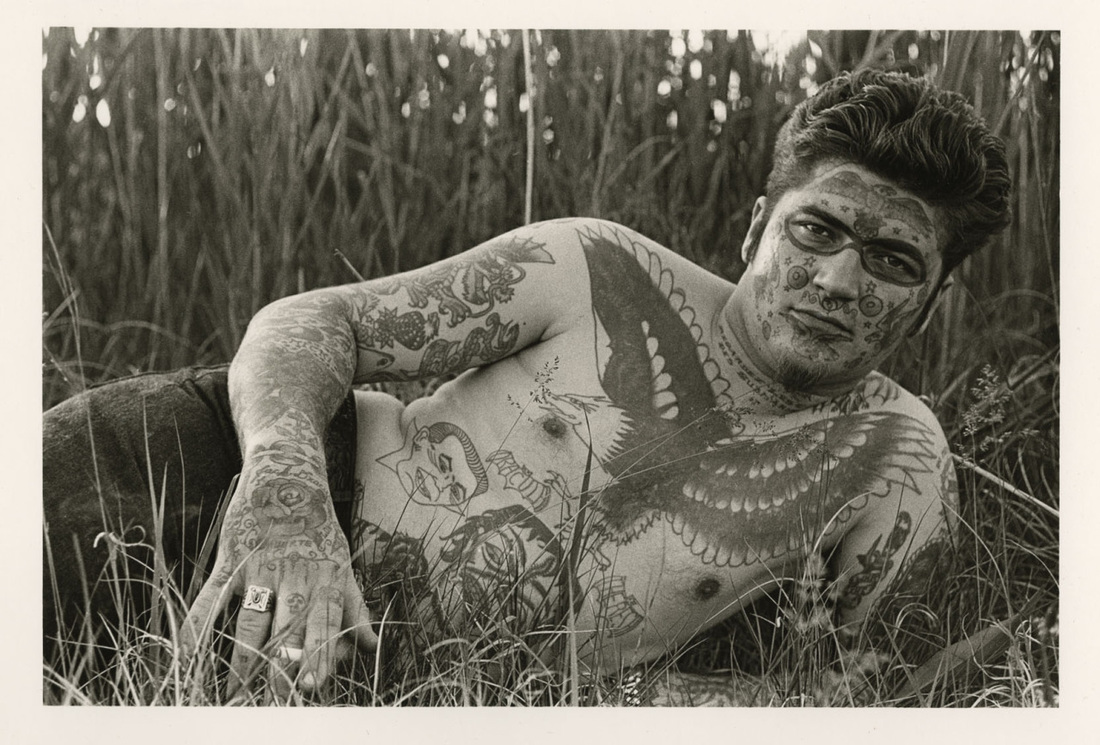

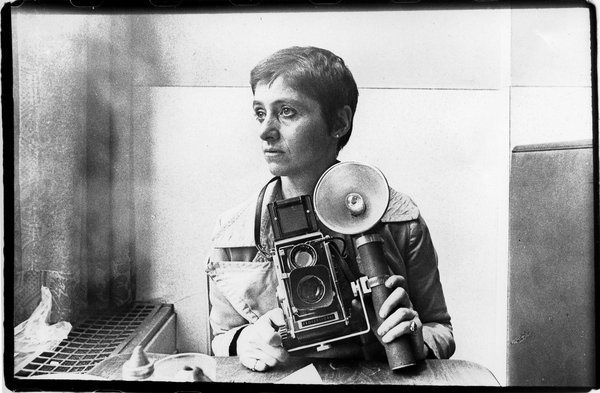

The image above, like the majority of Arbus portraits, is taken face-on, so that the viewer has a direct confrontation with the subject of the photograph. It is this aspect of her work, as much as the content matter, that is so unsettling. There is no opportunity to avert the eye, to focus on another portion of the image and try to alter the perspective. Unlike her early fashion shoots, these are not contrived studio sessions but are taken in the sitters’ own homes, institutions or workplaces, so that it is we who find ourselves in unfamiliar settings, alienated, confronted with people and places that may make us uncomfortable. The fact that many of her sitters appear quite at ease with their physical or mental awkwardness, or even proud of their disfigurements, challenges us to identify who it is that has the real problem.

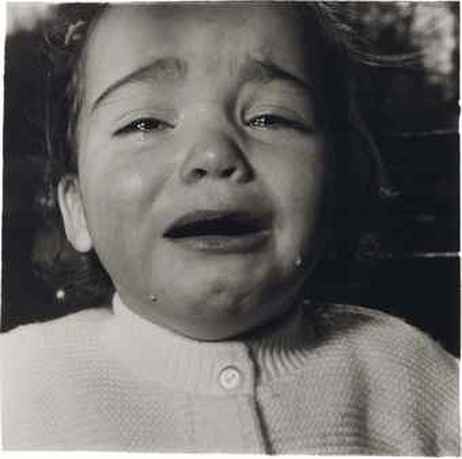

However, not all the sitters appear comfortable with being photographed, and in the case of those with severe mental disabilities it is evident that their consent was never – and could never – be obtained. The photographer’s troubled life – after several bouts of depression Arbus committed suicide at the age of 48 – invites connections with these images of loneliness, marginalisation and suffering. Does evidence of her own unhappiness demonstrate a degree of affinity or sympathy with those she photographed? There is an honesty about her photography that undermines accusations of voyeurism or exploitation, although such charges have been made. Influential critic Susan Sontag expressed her unease about Arbus’s work in her 1973 New York Review of Books article ‘Freak Show’, which was later revised to form the central essay in On Photography (1977.) Surprisingly, for such a respected writer, Sontag never really strikes home with any critical insight about Arbus’s work. The essay is effective in articulating Sontag’s negative response, but reveals little about the photographs themselves. Her main charge – that of a lack of compassion – has ‘stuck’ nonetheless, and it is no simple matter to dismiss.

One might argue that developing a ‘lack of compassion’ is an occupational hazard for any photographer working in the documentary tradition, particularly those commissioned to record scenes of suffering in war zones or disaster areas. Maintaining a high degree of detachment is essential for professional standards: but where does one draw the line? And does the practice of enforcing such discipline not run a risk of psychological self-harm? The story of Kevin Carter (1960-94) remains a salutary warning; the life, work and death of the South African photographer was dramatised in the film The Bang-Bang Club (Steven Silver, 2010) and inspired Alfredo Jaar’s unbearably moving art-installation The Sound of Silence (2006.)

Diane Arbus’s life has also been depicted on the big screen, providing the inspiration for the film Fur (2006) directed by Steven Shainberg. Like his earlier Secretary (2002) it is an audacious portrayal of a woman’s unorthodox desires, but as a portrait of Arbus it is unsatisfactory. Those wanting to know more about her should begin by studying her photographs – and for anyone in the region of Kirkcaldy, their exhibition remains open for another month, until the end of May.