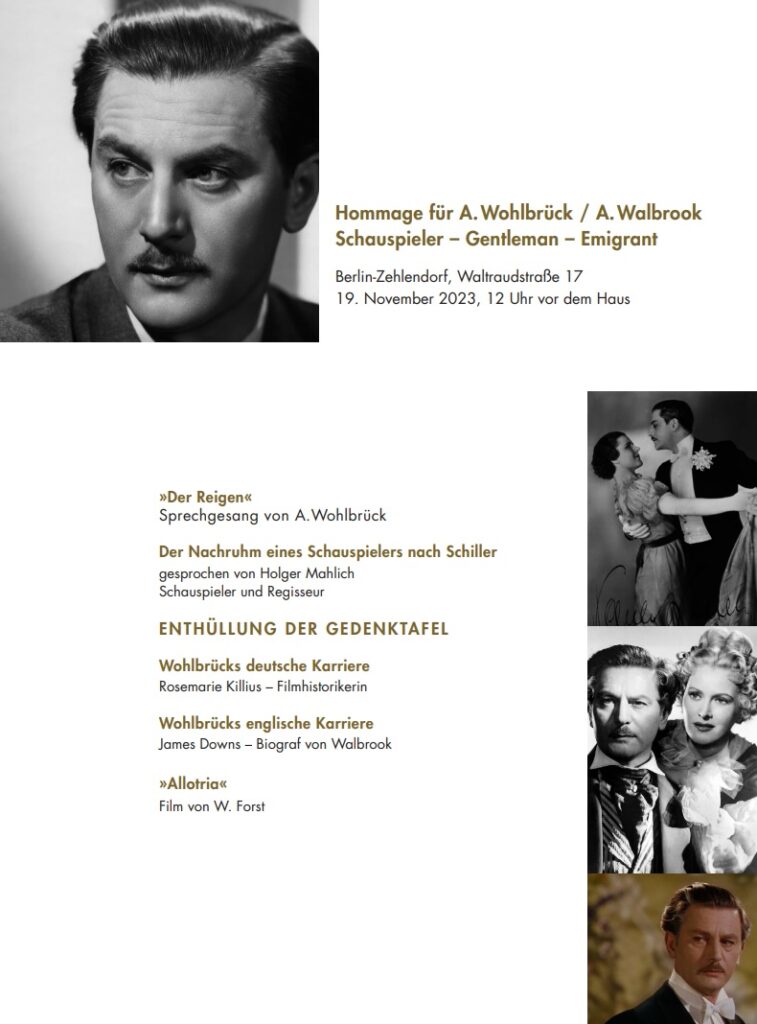

A house in Waltraudstraße, in a leafy suburb of southwest Berlin, was AW’s home from the autumn of 1934 until his departure for Hollywood (and then onto the UK) two years later. On 19 November this year – the anniversary of the actor’s birthday – I was delighted to take part in a programme of events at the house in which a plaque was unveiled to commemorate AW’s time here.

The programme was organised by Dr Rosemarie Killius, who had already hosted a similar ‘Hommage’ for Maria Cebotari in Vienna, as well as other events relating to AW in Frankfurt and elsewhere.

We were joined for the occasion by actor and director Holger Mahlich, whose father-in-law was Wolfgang Liebeneiner (1905-87), an actor and director at the Munich Kammerspiele, Preußisches Staatstheater, UFA studios and other venues familiar to AW – they probably met at some point. Holger read out a passage from Schiller, ‘Der Nachruhm eines Schauspielers’ [‘The posthumous fame of an actor’], after which Dr Killius gave an overview of AW’s film career in Germany, and I added a few words on his life in England.

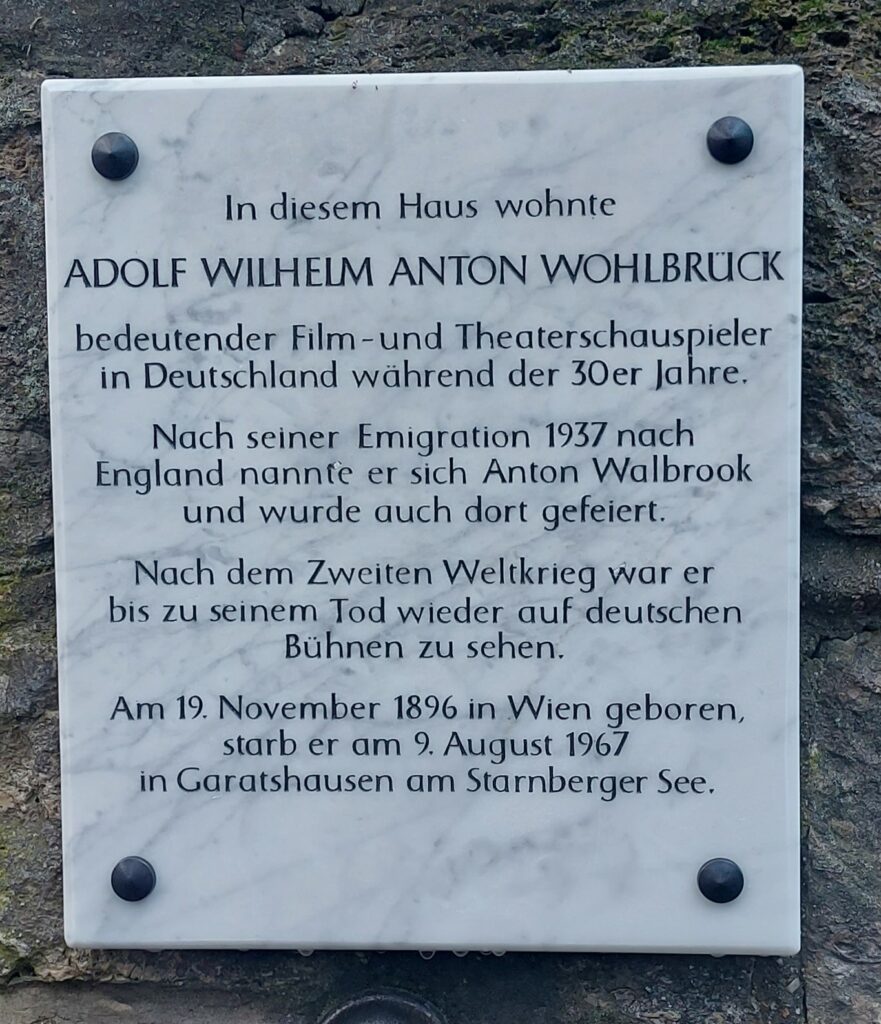

Dr Killius and I then unveiled the plaque:

Thanks to the kind generosity of the current owners of the house, we were all invited inside for drinks and home-made cake. The interior of the house remains substantially unchanged since AW lived here, and as the cultural tastes of the owners mean that the rooms are full of books and paintings, as well as a grand piano and numerous sculptures, it was not hard to imagine AW living here in similar surroundings. Some glimpses into the actor’s life here can be found in Hanna Heßling’s article, ‘Zigeunerbaron zu Hause: Adolf Wohlbrück plaudert am Kamin,’ Mein Film, No. 484 (1935), pp. 4–6, and in Werner Holl, Das Buch von Adolf Wohlbrück (1935), pp. 44–5.

I’d always understood the house to be located in Zehlendorf, but the owner explained to me that the boundary line between Zehlendorf and Dahlem runs up the middle of the street, with AW’s house lying on the Dahlem side. As this is regarded as a more desirable district, the houses on this side are – rather absurdly – priced far higher than those across the road.

These houses were all built in the early 1930s so presumably AW was the first occupier. The land, I believe, was owned by the industrialist Oskar Pintsch (1844–1912) and his wife Helene (1857–1923), patrons of the Oskar-Helene-Heim für Heilung und Erziehung gebrechlicher Kinder – an orthopaedic home for children and others with disabilities – which used to stand just up the road, and which gives it name to the local U-bahn station. I’m not sure if there is any link between their philanthropic ideals for healthcare and the construction of the houses, but AW’s house is beautifully designed. Each room has two doors, so that you can walk around each floor in a circle, from room to room, and if all the doors are opened natural light floods in from all four sides.

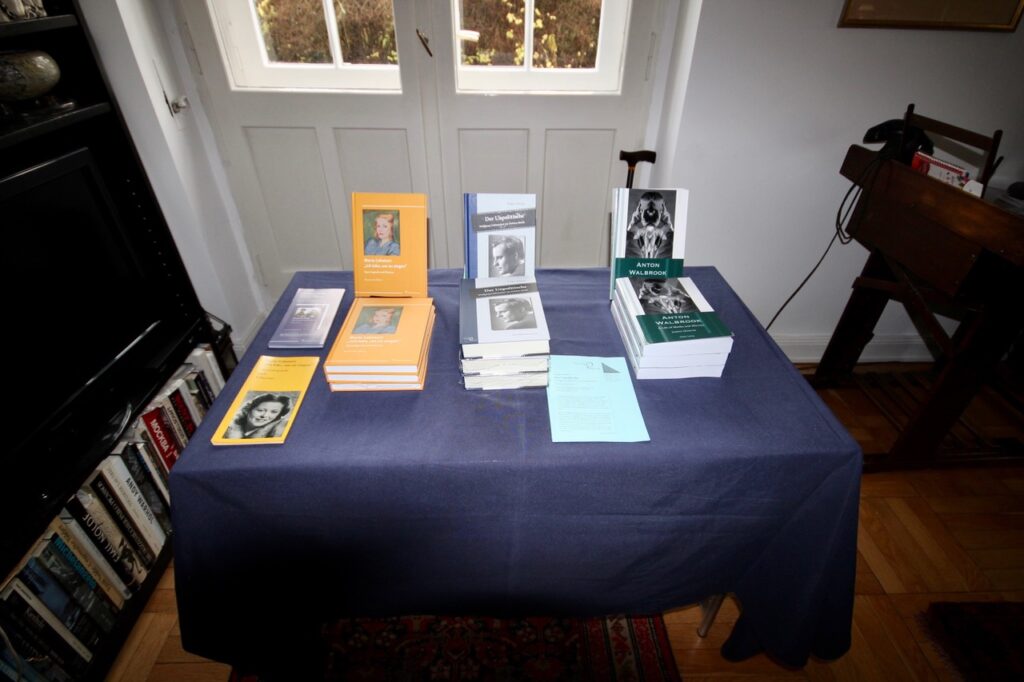

Also present in the house was Frau Dr. Karin Timme, of the publisher Frank & Timme GmbH, with whom we are having some discussions about a possible German translation of the biography. Copies of the book were for sale, alongside Holger Mahlich’s biography of Wolfgang Liebeneiner, and Dr Killius’ book on Maria Cebotari.

Afterwards, a group of us went to the nearby local history museum, the Heimatmuseum Zehlendorf, for a special screening of Allotria (1936), the stylish and fast-paced comedy in which AW co-starred with Renate Müller (for the fourth time), Hilde Hildebrand (for the sixth time), Heinz Rühmann and Jenny Jugo. All in all, this was a wonderful day, and we are all deeply indebted to Dr Killius for her hard work in organising the Hommage and for commissioning the design and construction of the plaque.