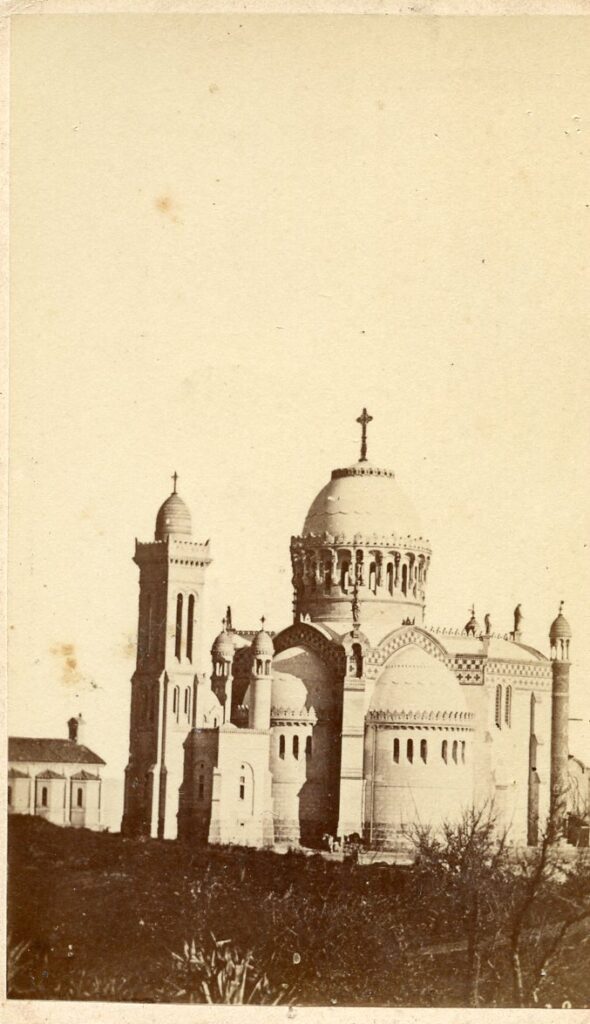

Although most of my carte-de-visites are portraits, a number of them show landscapes, usually views of famous buildings or picturesque sites. Among these is the card below:

On the reverse of the card is this:

This cdv shows the Neo-Byzantine Basilica of Notre Dame d’Afrique (Our Lady of Africa) in Algiers, designed by architect Jean-Eugène Fromageauand built between 1858 and 1872. The cdv seems to have been issued (and perhaps sold) by the Cistercian abbey at Staouéli, some seventeen miles away, which was founded in 1843 by French monks from the abbey of Aiguebelle. Although the Cistercians had a reputation for asceticism and austerity, the motives behind the foundation were not entirely spiritual, and were in fact closely associated with the French colonization of the country, which lasted from 1830 until Algerian independence in 1962.

The Coming of the French

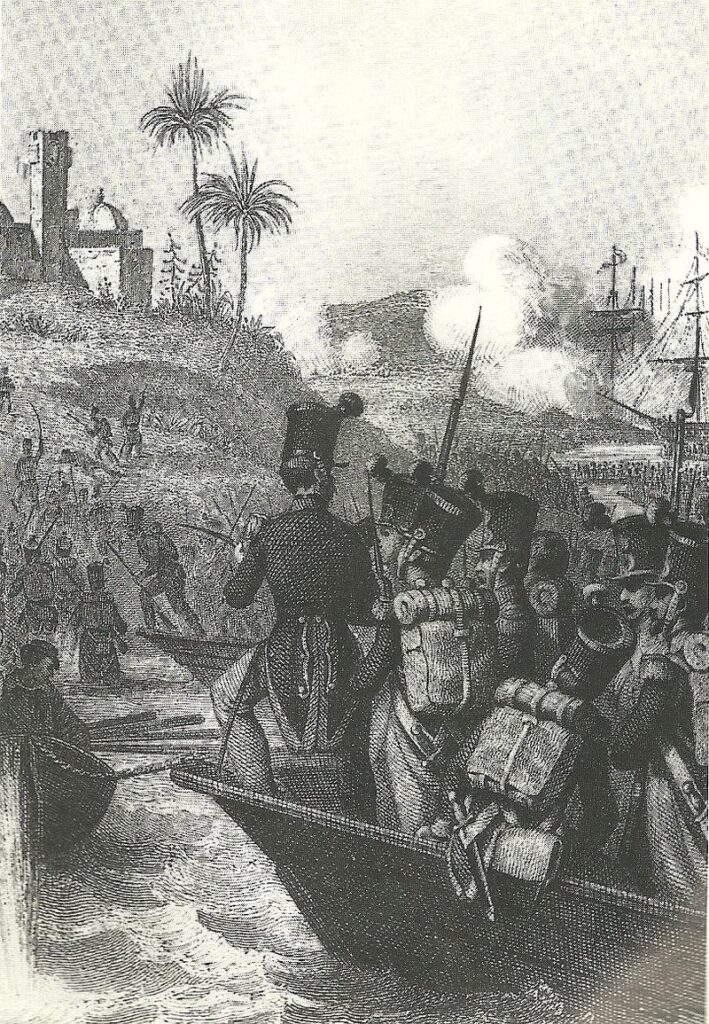

The French invasion of Algiers was undertaken for a number of reasons, including a wish to end the attacks by Barbary pirates who operated out of Algiers and the need to distract the French population from their dissatisfaction with King Charles X. The immediate catalyst for the invasion was an altercation between Hussein Dey, the Ottoman ruler of Algiers, and the French consul Pierre Deval, during which Dey was alleged to have struck Deval with his fan. An armada of 600 ships sailed from Toulon and around 34,000 troops under General de Bourmont landed at Sidi Ferruch, about seventeen miles west of Algiers, on 14 June 1830.

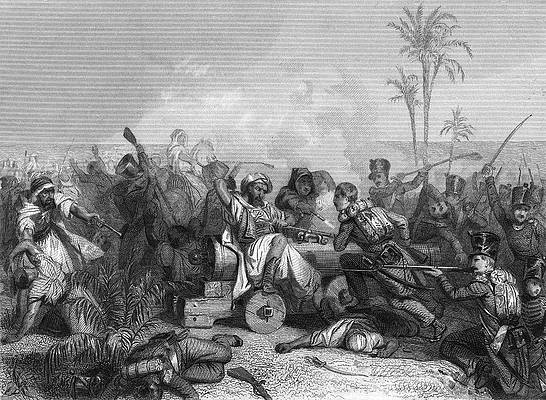

Hussein Dey sent an army of around 24,000 soldiers to meet the French forces, who had encamped at the edge of the plain of Staouéli, which stretched between the Atlas mountains and the coast. The two sides clashed on 19 June and, despite having a few advantages, the Algerian forces were defeated at the ‘Battle of Staouéli’ due to French superiority in artillery power and military discipline. Further skirmishes followed on the 24 June but the French were soon able to begin marching to Algiers, where the city was taken on 5 July. Hussein Dey surrendered and went into exile, leaving Algeria to remain under French occupation for over 130 years.

The Coming of the Monks

At first the French administered Algeria as a military colony with the focus on the regions around the coast, but over time this policy changed to one of colonial expansion and total control across the whole country. Land was seized and offered to French settlers, factories and businesses were set up, and those in the French army and administration were encouraged to make private investments into land speculation and agricultural production. The Algerians continued to resist throughout the 1830s and 1840s, however, particularly under the leadership of Abd Al-Qādir. After a decade of costly fighting, a French delegation was set up to review the future of a colony in Algeria, and their report concluded that the country ‘…would cease to be French if she was not Christian.’ It was thought that the presence of a religious community in the colony would help to establish Christianity in the region, encourage a more positive view of the French settlers, and bring about some peace and stability. The Cistercians were the ideal choice, given their agricultural expertise and reputation for austere holiness.

After a preliminary visit in September 1842 by Abbot Orsise Carayo of Aiguebelle and Abbot Hercelin of La Trappe, a plot of land was chosen on the Staouéli plain. The site occupied 1000 hectares of rough ground between Wadi Bridja to the east and Wadi Boukara to the west, covered in dwarf palms, mastic trees and wild myrtles. The first monks arrived here on 13 September 1843 and the foundation stone for the monastery, dedicated to Notre Dame de la Trappe de Staouéli, was laid the following day, the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, by Dom François-Régis and blessed by the bishop of Algiers, Mgr Dupuch in the presence of General Bugeaud. The relationship between the monastery and the military remained close, with General Marengo using his personal wealth to stave off financial crisis in 1847 as the abbey farm had a disastrous year

The monastery church was consecrated on 30 August 1845 and raised to the status of an abbey the following year, as the community grew from 67 monks to around 120, bolstered by the addition of monks from the abbes of Bellefontaine and Melleray. One of the monks had actually been a soldier who had fought during the Battle of Staouéli. These early years were hard, however; the land was poor and unsanitary, with malaria claiming the lives of many of the monks. Over time, they gradually succeeded in establishing olive groves and mulberry trees, draining the marshes and planting hedges of cypress and bamboo to shelter their fragile crops from the strong sea winds. In 1853 the monks won first prize at the Agricultural Exhibition in Algiers, and when Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenie visited Staouéli on 4 May 1865 they marvelled at what had been achieved.

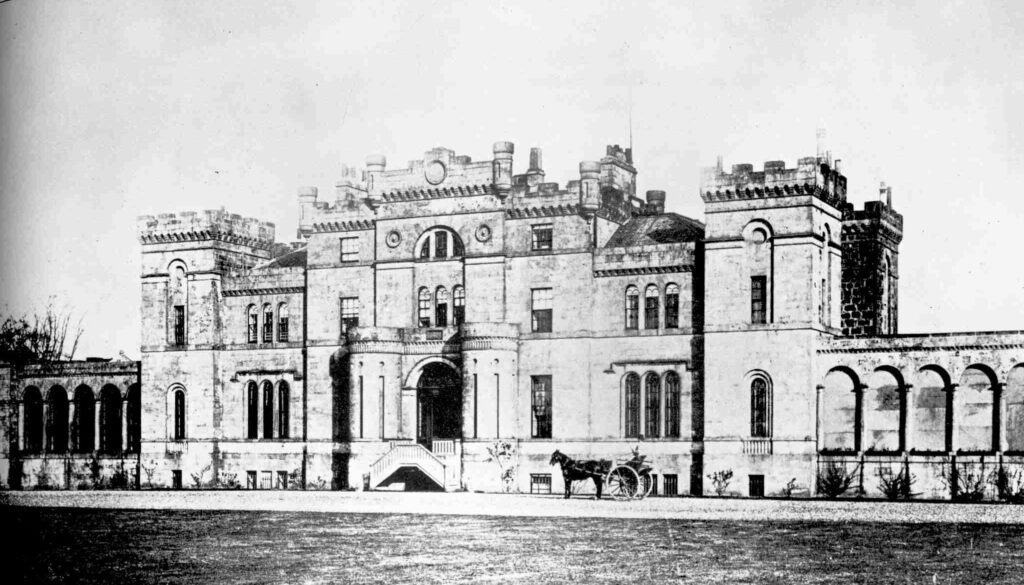

The Abbey

The main monastic buildings were built on two storeys around a cloistered courtyard garden, with the chapel occupying one wing, the kitchen and refectory on the ground floor, and the dormitories and infirmary up above. on the first floor. The farm lay on one side of the abbey, and on the other side a complex of workshops and other outbuildings, including a bakery, laundry, dairy and forge. It was a far simpler building than the magnificent basilica that was being constructed in Algiers. There is no mention of a photographic darkroom among the workshops in descriptions of Staouéli that I can find, and it is not clear if these cartes-des-visites were bought in commercially for resale as souvenirs at the abbey, or if they were in fact taken by a Trappist monk. There is no doubt that other such images were in circulation, as I have another cdv:

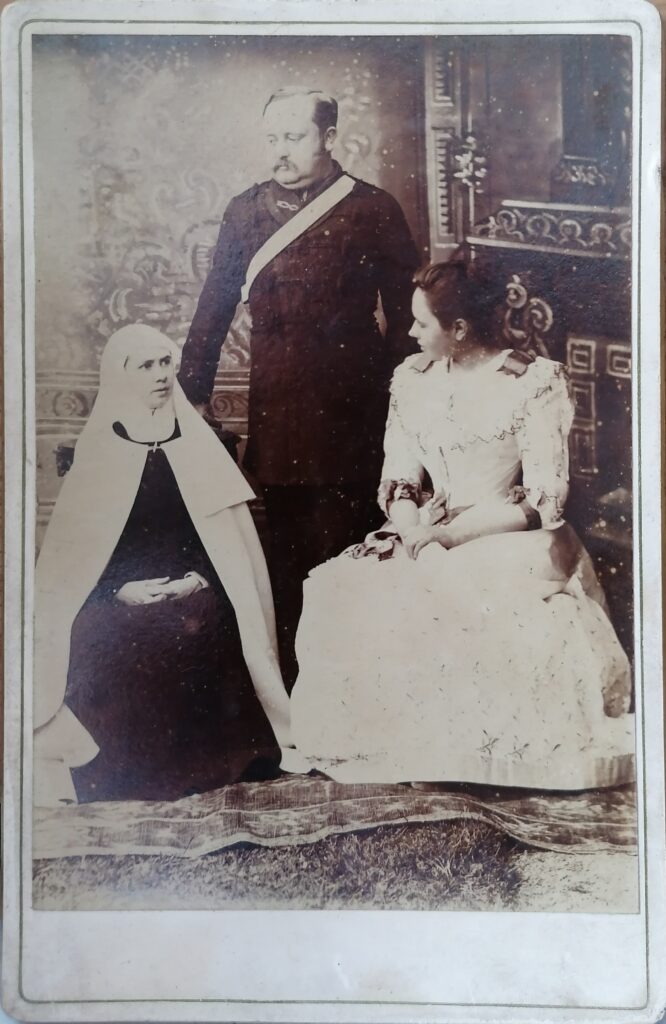

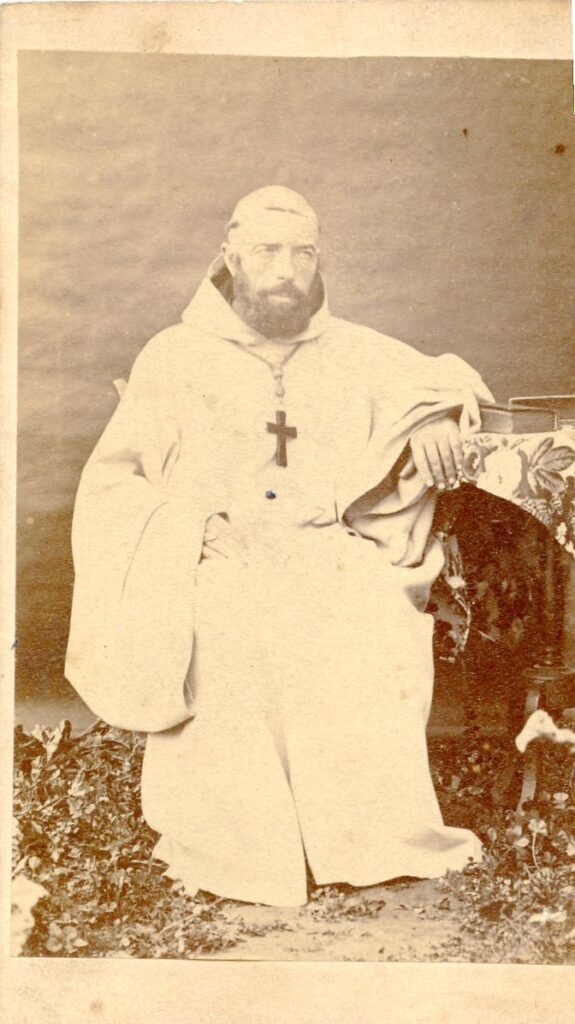

Dom Marie-Augustin Charignon OCSO (1818-93)

2nd Abbot of Staouëli 1856-1893

This cdv also has the abbey’s name printed on the back, but in a different font, and with some decorative work around the letters. Someone has helpfully added a pencil note to identify the portrait as that of Dom Marie-Augustin Charignon.

A merchant’s son, he was born Flavien Charignon on 21 February 1818 in Peyrus (Drôme), and entered the novitiate at the Cistercian abbey of Aiguebelle in 1845. After ordination, he rose to become the monastery’s prior, after which he was sent to Staouëli where he served in the same role.

When Abbot François-Régis de Martrin-Donos was transferred to Rome as Procurator-General in 1854, Dom Augustin took over the running of the abbey. He was consecrated as Abbot of Staouëli in December 1856 by the Bishop of Algiers, Louis Pavy, who was the man responsible for the construction of Basilica of Notre Dame d’Afrique. Work began on the cathedral, which was designed by architect Jean-Eugène Fromageau, two years after Abbot Augustin’s consecration. Louis-Antoine-Augustin Pavy (1805–1866) was the second bishop of Algiers, but he died without seeing the cathedral completed.

Dom Augustin, on the other hand, remained Abbot of Staouëli for almost four decades, until his death at the abbey on 29 December 1893, just a few months after celebrating the abbey’s golden anniversary on 21 July 1893. He was succeeded by Abbot Louis de Gonzague Martin (1893-1898), who was the superior when Charles de Foucauld (then a Trappist novice at Akbés ) stayed at Staouëli for a few weeks between 25 September and 27 October 1896. The abbot had been one of the co-founders in 1882 of the Syrian monastery of Notre-Dame-du-Sacré-Cœur (La Trappe de Cheïkhlé) in Akbés near Aleppo, which became a dependent house of Staouëli in 1894. After his death in 1899 he was succeeded by Dom Louis de Gonzague André (1898-1904), the fourth and final abbot of Staouëli. By the early 1900s the abbey’s prospects were not looking good: there were no local vocations and the French government was enforcing strict separation of Church and State that threatened the confiscation of church property and the expulsion of religious orders from France. It was in sharp contrast to the close relationship between the monks and the French authorities that had flourished at the time of Staouëli’s foundation. To pre-empt the possible seizure of the abbey, Abbot Louis sold Staouëli in 1904 and transferred the entire community (apart from one monk) to Maguzzano on the shores of Lake Garda in Northern Italy.

Postscript: Staouëli and the Atlas martyrs

The monks remained at Maguzzano for over thirty years before the monastery closed in 1936. Their last abbot had been another monk of Aiguebelle, Bernard Barbaroux, who had been appointed Abbot of Maguzzano in 1930. The buildings were sold off in 1938, around the same time as another group of Trappist monks were starting a new foundation in Algeria. Our Lady of Atlas was situated at Tibhirine, some 20 km from Médéa and 100 km south of Algiers. In 1947 it was granted abbatial status, and Dom Bernard Barbaroux was consecrated as the first abbot on 26 September 1947, using Abbot Augustin Charignon’s old crozier from Staouëli. Several monks from Staouëli were members of this community, which continued its quiet life of work and prayer throughout the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62), although numbers decreased over the decades and in 1984 Our Lady of Atlas was demoted from abbey to priory status. That same year, Dom Christian de Chergé OCSO was elected prior.

Ever since independence in 1961, Algeria had been governed by the National Liberation Front (FLN) and was a one-party state until the mass riots of October 1988 forced a reform of the constitution. The new democratic system was tested by local elections in June 1990 when the FLN lost heavily to the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). When it became clear that the FIS were going to win the parliamentary elections following the first round of votes in December 1991, the army moved in to halt the electoral process and declare a state of emergency, precipitating a civil war that would last for over ten years. There were two main Islamist groups that took up arms to fight the government, the Islamic Armed Movement (MIA) and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA). On 27 March 1996 members of the GIA arrived at Our Lady of Atlas and kidnapped Dom Christian and six other monks. They were held for two months with the offer that they would be released in exchange for a captured GIA leader. Negotiations failed, and the seven monks were executed on 21 May. A funeral Mass was said for the monks on Sunday 2 June at the Basilica of Notre Dame d’Afrique.

These two cdvs thus represent scenes from the long, complex and troubled history of French monastic involvement in Algeria. I have some other old photographs and postcards that can add to this story, but will keep them for another time.