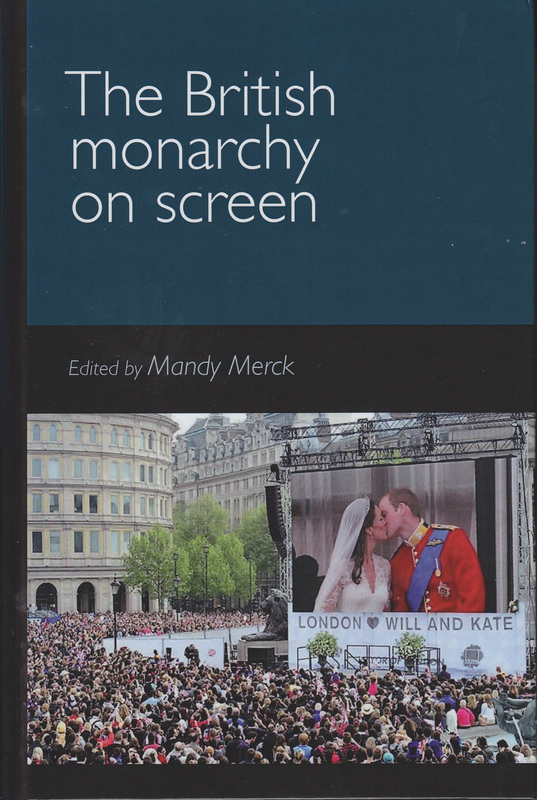

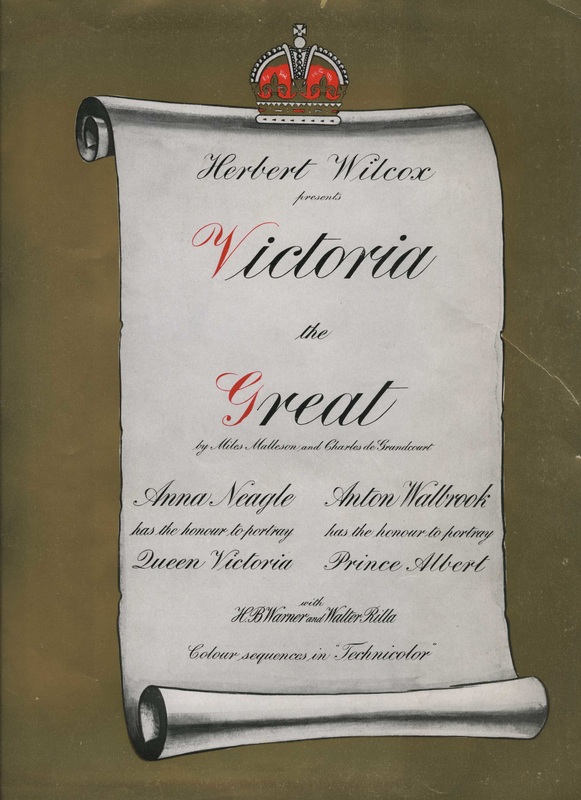

The first thing to strike the eye is, of course, the change of cover picture, and I must confess to feeling a stab of disappointment in seeing that Anton was no longer on the cover, unlike in the the original proposed version (right.) This photograph of AW and Anna Neagle together in Victoria the Great does however appear within my chapter along with another still from that film showing AW seated at the piano surrounded by young ladies of the royal court. Mine was not the only paper to look at Wilcox’s films, and Professor Steven Fielding’s ‘Heart of a Heartless World: Screening Victoria’ discusses the political aspects of the films in comparison with other screen portrayals of the queen.

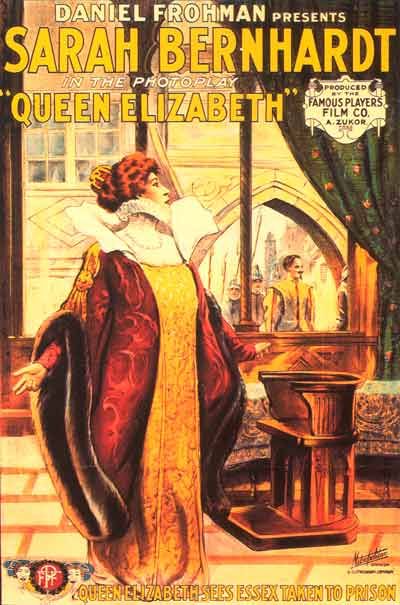

Despite inevitable overlaps like the above, an impressively diverse range of films and television programmes come under scrutiny, beginning with Victoria’s early involvement with photography and her depiction in silent cinema – such as the lost Sixty Years a Queen (Barker & Samuelson, 1913) and Queen Elisabeth (Desfontaines & Mercanton, 1912) starring Sarah Bernhardt (below.)

Moving beyond Sarah Bernhardt’s performance, cinematic portrayals of Elizabeth I proved a popular subject for examination. One paper was devoted to Quentin Crisp’s casting in the role in Orlando (Sally Potter, 1993) while another cast a critical eye over a series of film interpretations – Flora Robson in Fire Over England (Korda,1937), Bette Davis in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (Curtiz, 1939) and The Virgin Queen (Koster, 1955), Jean Simmons in Young Bess (Sidney, 1953), Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth (Kapur, 1998) and its sequel Elizabeth: the Golden Age (Kapur, 2007) as well as Judi Dench in Shakespeare in Love (Madden, 1998) – for which she won an Oscar, despite only being onscreen for about eight minutes.

Her award reflects something of the iconic prestige that is attached to screen portrayals of royalty – an association that received extensive, and sometimes critical, attention during the conference. One key theme was the way in which both the monarchy and film-makers exploit each other to further their own interests- The Queen (Frears, 2006), for example, was described by David Thomson as ‘the most sophisticated public relations boost HRH had had in twenty years’, while directors such as Herbert Wilcox were equally adept at endowing their promotional materials with symbols of regal status:

Hello,

The “Victoria The Great” cover was far better than the new…I think the editor wanted something more catchy (what is more catchy than William and Kate? ;-))

Regards,

Marieno.

Hello Marieno, I’m inclined to agree with you, as I think Anton’s appeal has a timelessness about it that is not shared with W&K – but then again, I can hardly pretend to be unbiased on the matter.

Pingback: Caroline Young, Classic Hollywood Style (Francis Lincoln Limited Publishers, 2012) – Dark Lane Creative