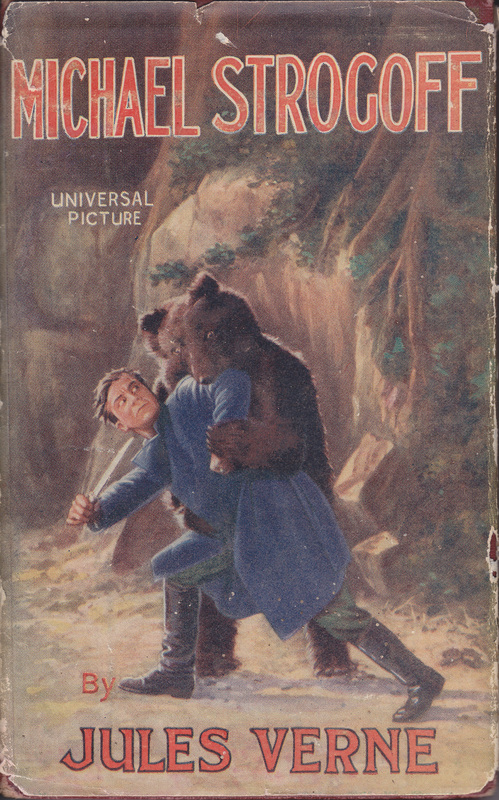

Jules Verne’s novel Michael Strogoff: the Courier of the Csar was first published in 1876 and is regarded as one of his finest works. It is a stirring tale, concerning the adventures of Michael Strogoff, who acts as courier for Tsar Alexander II and has to dash across Siberia to warn the Tsar’s brother – governor of Irkutsk – of planned treachery by a local Tartar warlord named Ivan Ogareff. Strogoff encounters various characters on his journey – Nadia, daughter of a political exile, two journalists reporting the war – as well as his mother in Omsk, where he is captured while visiting. Nadia and Strogoff’s mother are forced to watch as Michael is (apparently) blinded with a hot blade by the cruel Tartars, but he later escapes and reaches Irkutsk where Nadia’s father helps defeat the rebellion, before giving Strogoff his daughter’s hand in marriage.

The novel was adapted for the silent screen in 1926, with Ivan Mozzhukhin in the title role – the same actor also played Hermann in an early silent version of The Queen of Spades (Protazanov, 1916), endowing him with the rare distinction of prefiguring AW’s roles in two films. In 1935, although less than ten years had passed since Tourjansky’s movie, it was decided that the time was ripe for a remake (as I said above, nothing is new in the movies!), taking advantage of the advent of sound and improved technology.

I’ve written elsewhere about certain scenes in the film where AW’s posture evokes the iconography of Saint Sebastian but here I want to focus on his fight with the bear. As readers of this blog are probably aware, the actor was actually a great animal lover, and I’ve collected together a number of postcards and images celebrating this here. The scene perhaps jars less with the actor’s personal attitude when it is understood that Strogoff kills the animal while defending a helpless woman who has fainted in fright at the bear’s feet.

In the novel, the incident occurs in Part I, Chapter XI (pp.76-77 in my copy of the film tie-in shown above) and differs considerably from the screen versions. Here, Strogoff and Nadia are travelling through the forest in the company of the two journalists when ‘a monstrous bears’ bursts out the trees and attacks their horses. Nadia tries to defend the horses with her gun, but Strogoff leaps between her and the animal, knife in hand, and swiftly despatches the bear, executing ‘in splendid style the famous blow of the Siberian hunters.’

In the film Der Kurier des Zaren (Eichberg, 1935), the bear attack takes place on board a ship. Strogoff and Nadia (Maria Andergast) are among many passengers watching a group of gypsies on deck, one of whom is goading a ‘tame’ bear to perform tricks for their entertainment. The animal is startled by the magnesium flash on the journalists’ camera, attacks its trainer and breaks free. Strogoff runs forward to save an elegantly-dressed lady (Hilde Hildebrand) who has collapsed in fright, little knowing that she is in fact Zangara, the lover of Ogareff, who will later betray him.