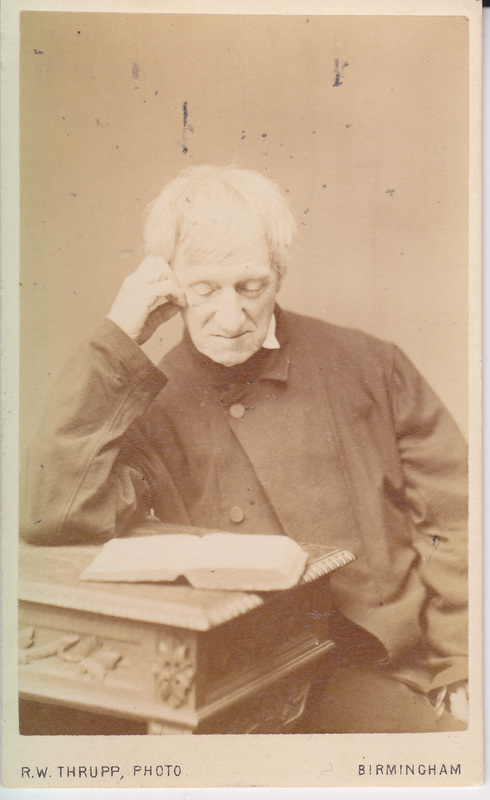

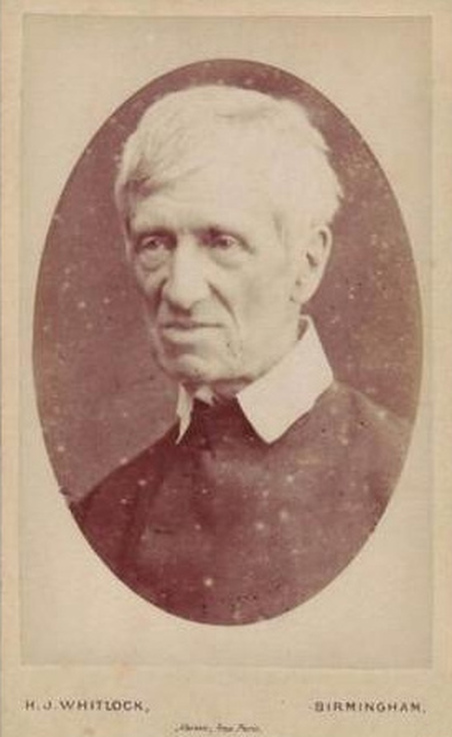

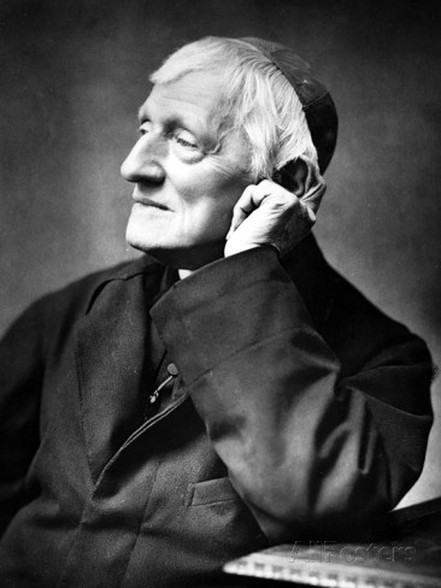

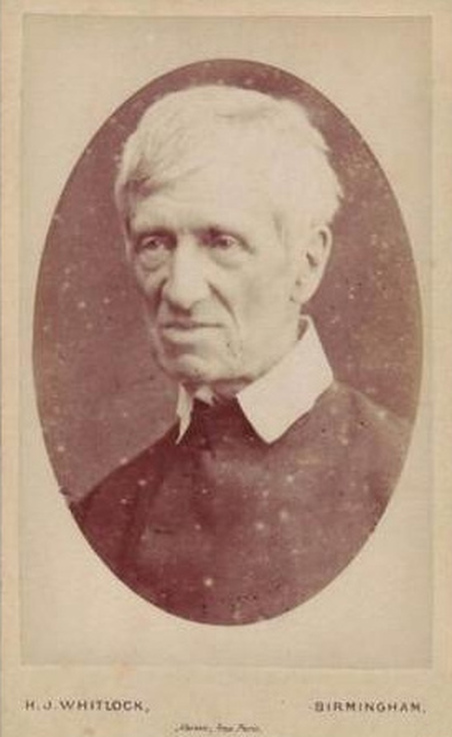

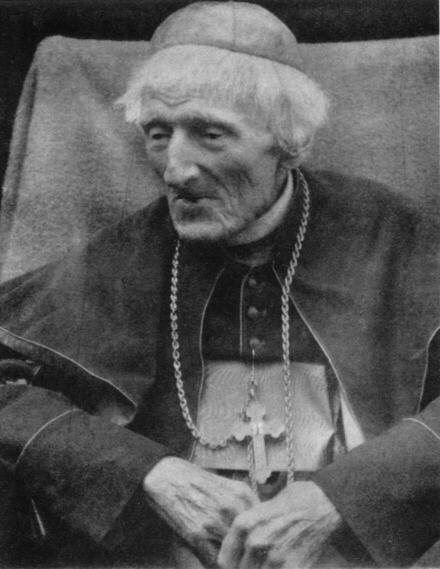

This week’s cdv was acquired fairly recently for about 50 pence, and I suspect it would have cost much more had the seller known the identity of the sitter. John Henry Newman (1801-90) was one of the most influential religious thinkers and writers of the 19th century, and the portrait reflects his reputation for scholarship.

Newman’s writings and leadership of the ‘Oxford Movement’ in the 1830s and 1840s transformed the Church of England, but he became a Roman Catholic in 1845, was ordained a priest and joined the the Congregation of the Oratory. He was leader of the Oratorian community in Birmingham, where this photograph was taken.

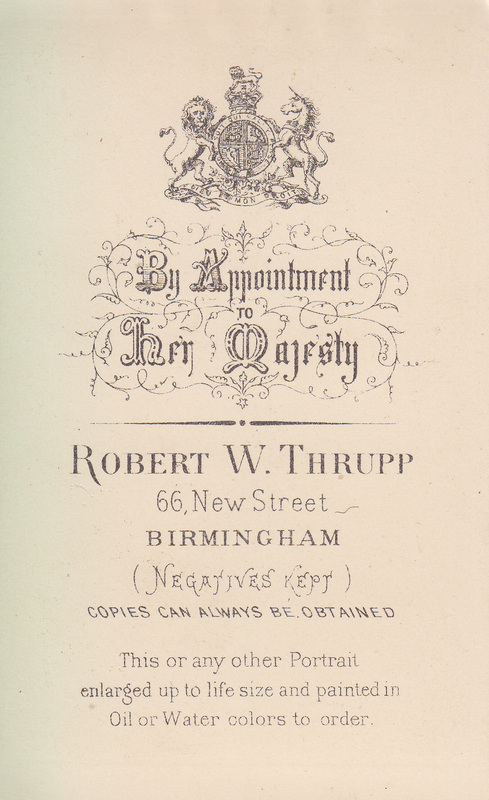

Robert White Thrupp (1821-1907) had a studio at 66 New Street from 1867 to 1887, and this portrait was probably taken there in the late 1860s. Earlier in his career he had been a financial adviser to Windsor & Newton, and ran a printselling business at 66 New Street in partnership with Samuel W Hill. In 1862 they added a photographic studio to the premises and went into business with Napoleon Sarony. Hill left in 1863 and after Sarony returned to America in 1866 Thrupp bought his negatives and began running the business under his own name. It is interesting to see Thrupp offering the option for portraits to be ‘enlarged up to life size and painted in Oil or Water colors.’ Miniature portrait painters suffered the most from the rise of professional photography, and many followed the adage ‘if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em’, swapping their easels for cameras. The tangled relationship between art and photography is a fascinating field of study, and one its many paradoxes is the idea of people choosing to be photographed rather than painted, only to pay to have the photograph turned back into a painting.

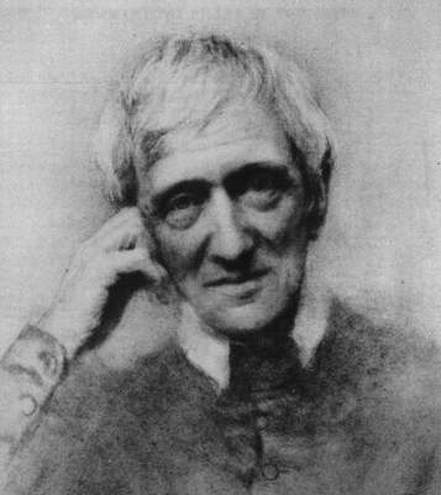

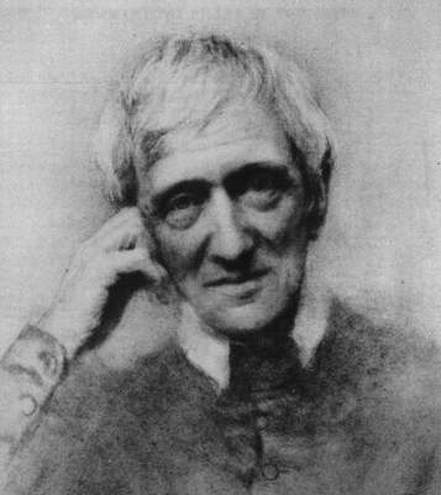

A few well known paintings of Newman are known to have been worked up from photographs, and the famous chalk portrait by Lady Jane Coleridge, (below) was based on a photography by Thrupp taken around the same time as my cdv:

J H Newman in 1874, by Jane (née Fortescue Seymour), Lady Coleridge. Black chalk with black & white ink

Newman was photographed several times in his life, and perhaps a chronological list of these might be of interest:

1861 – Heath & Beau

At the end of November 1861 Newman went up to London for a few days. He stayed at 28 Portland Place, the house of his friend Henry Bowden, and in his diary for 27 November he noted ‘went to photographer.’ He recorded in his diary on 4 December 1861 that he ‘went two or three days to Photographer’ and In a letter to Ambrose St John written from Portland Place the same day, he revealed that the sessions had not been straightforward:

‘As to the Photographs, they came (in proof) last night, and are not quite satisfactory – The man wishes to try again – and I am going to him in an hour’s time – The want of light is the difficulty at this time of year.

3 pm. I have been to the man – he has taken four more photographs – but the light died away and he is not satisfied – he is going to print off some copies – but I am to go to him again, for another attempt. He charges nothing more – but he wants me to let him publish, which I have not granted.’

– Letters & Diaries XX, p.74.

Henry Charles Heath (1824-98) and Adolphe Paul Auguste Beau (1828-1910) ran a studio together at 283 Regent Street, Westminster, between 1861 and the dissolution of their business partnership in June 1863. It was therefore only a few minutes walk from Portland Place – and the repeated visits would not have been too inconvenient.

July 1863 – by Stanislas Bureau

Newman visited Paris with his friend William Neville between 21 and 24 July, during which time he called in at Monsieur Bureau’s studio at 44 Palais Royal, Rue Montpensier and had this portrait taken. The Frenchman had started his business in Paris in 1853 and this vignetted style of portraiture is typical of his work. He posted the photographs to Newman, and they were delivered to the Birmingham Oratory on 15 August 1863.

– Letters & Diaries, XX p.505

July 1864 – by Mclean and Haes

The following summer saw Newman in London for a few days, staying at the Paddington Hotel from the 18th to the 25th of July. On the morning of Thursday 21 July he wrote in his diary:

‘Breaktasted with Monsell; with him and Ambrose to MacLean for Photographs, and the Houses of Parliament, dined with Ambrose at Victoria Station – went to British Institution [for Promoting the Fine Arts] Pictures.’

– Letters & Diaries XXI, pp.159-60.

Thomas Miller McLean (born 1832) and Frank Haes (1833-1916) ran a photographic studio together at 26 Haymarket until their business partnership was dissolved in September 1865.

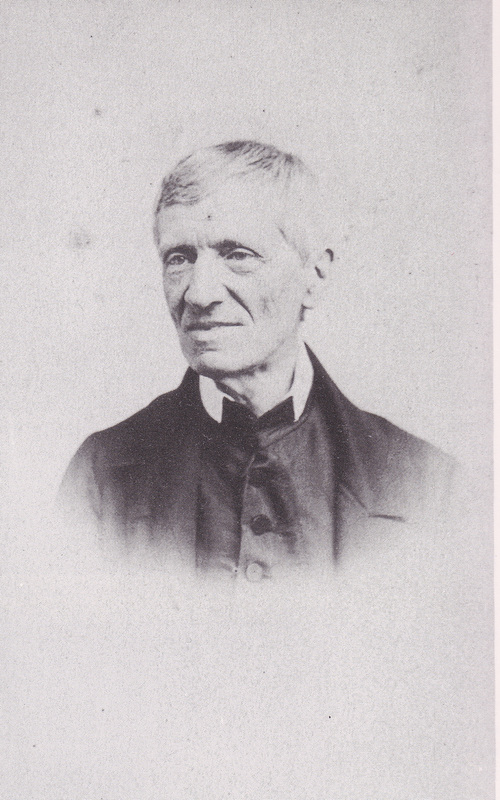

Another RW Thrupp portrait from the late 1860s

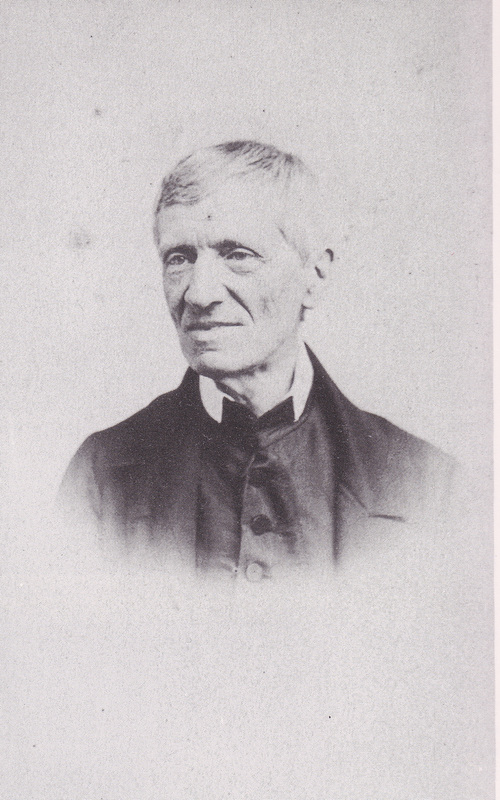

HJ Whitlock

Joseph Whitlock (1806-57) was the first professional photographer to establish a permanent studio in Birmingham; after obtaining a daguerreotype license from Richard Beard, he opened a studio at 120 New Street in January 1843. His son Henry Joseph Whitlock (1835-1918) began working for him in 1852 but moved to Worcester in 1855 to set up his own business. His father’s studio moved to 110 New Street and was looked after by his widow until her death in 1862, at which point Henry Joseph moved back to Birmingham and opened his own studio at 11 New Street. He ran a very successful business here for the next few decades, assisted by family members – his sons, brother and nephews were all photographers. Newman had his portrait taken here several times.

Another HJ Whitlock, this time showing Newman wearing spectacles

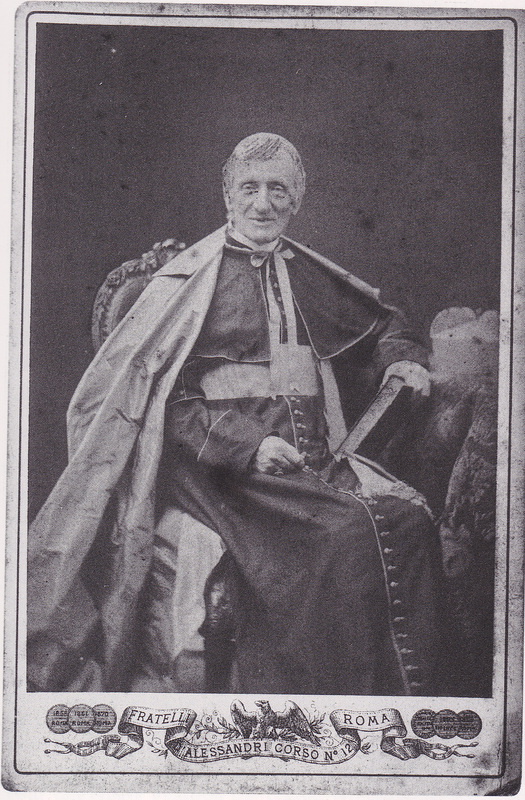

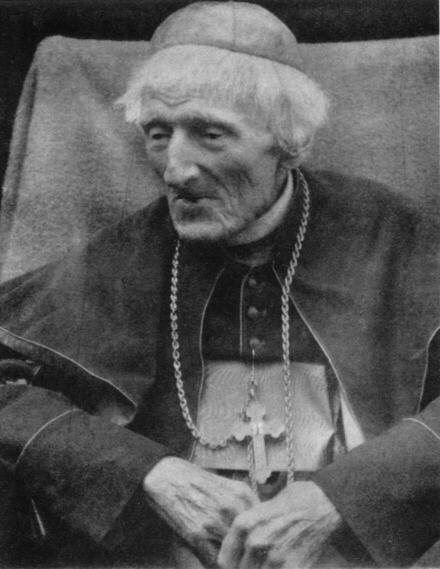

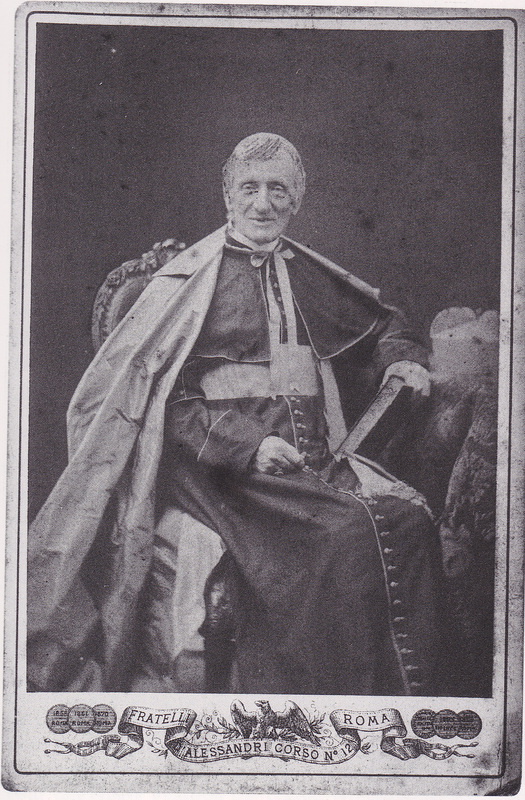

Newman was made a cardinal in Rome on 12 May 1879

1879 – Fratelli D’Alessandri

This official photograph to commemorate Newman’s elevation to the cardinalate was taken at Rome’s most prestigious studio, which was run by two brothers: Don Antonio (1818-93), a Catholic priest, and Francesco (1824-89) D’Alessandri, who together opened the first professional photographic premises in Rome in about 1858. They had a particular close link to the Vatican and photographed all the popes of their era, including Leo XIII who gave Newman his cardinal’s hat.

1880 – HJ Whitlock. Newman here wearing his ‘galero’ or cardinal’s hat, received the previous year

Another Thrupp portrait, probably early 1880s – Newman has episcopal dress on. The biretta would have been scarlet.

Comparing the back of Thrupp’s 1880s cdv to my one from 15 years earlier, it can be seen that he has introduced colour and more ornate decoration

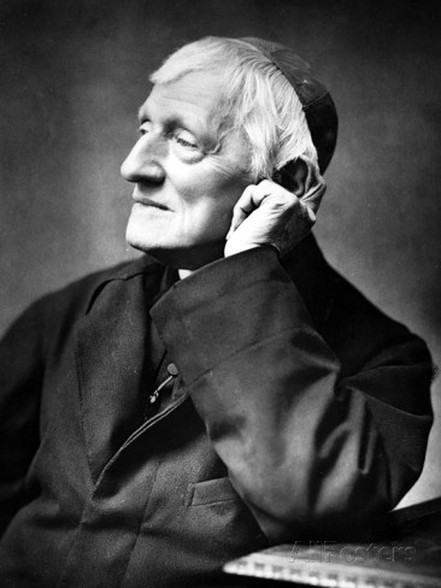

1885 – by Herbert Rose Barraud (1845-96)

Some books give the name of this photographer as Louis Barraud, although most seem to refer to him as Herbert Rose. It was published in 1888 in an early issue of his massive series, Men and Women of the Day: a picture gallery of contemporary portraiture, which was published in 78 monthly parts between January 1888 and June 1894 and eventually filled seven volumes. Barraud’s premises were at 263 Oxford Street although it is possible that he came to Birmingham to photograph Newman, who was now increasingly frail.

1889 – by Fr. Anthony Pollen Cong. Orat. (1860-1940)

This final portrait was not taken by a professional photographer, but by one of Newman’s fellow Oratorians, Father Anthony Pollen, who entered the Oratory in 1883, and was ordained priest in December 1889. He was the third son of John Hungerford Pollen (1820-1902) and brother of Jesuit scholar, Fr. John Hungerford Pollen SJ (1859-1925.) The latter was also a photographer, and both priests feature in my Ph.D research.