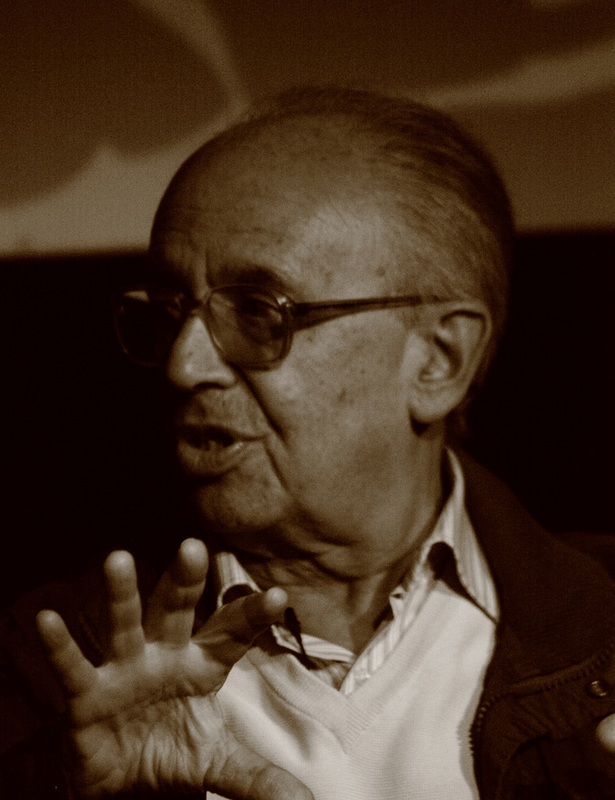

Peter Sasdy at 80

Peter George Sasdy was born in Budapest on the the 27th May 1935. Although he survived the war and the devastation of Budapest, he was forced to leave Hungary after the failure of the 1956 uprising. Arriving in England, he studied drama and journalism at Bristol University before joining ATV in 1958. His first task there was directing numerous episodes of Emergency Ward 10 (1959-60.) He was promoted to director of drama at ATV, before going freelance in 1964. His work included a range of series and standalone plays, ranging from police dramas such as Ghost Squad (1963-64), Isaac Asimov’s Caves of Steel (1964, his first collaboration with Peter Cushing) to two Brontë adaptations, Wuthering Heights (1967) and the four-episode series The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1968-69) starring Janet Munro as Helen Graham.

He also directed no less than three productions of Sherlock Holmes, beginning with an ITV episode in 1965 that starred Peter Cushing as the detective. This was later followed by the Polish-British co-production Sherlock Holmes (1979) starring Geoffrey Whitehead, and finally Sherlock Holmes and the Leading Lady (TV movie 1991) starring Christopher Lee.

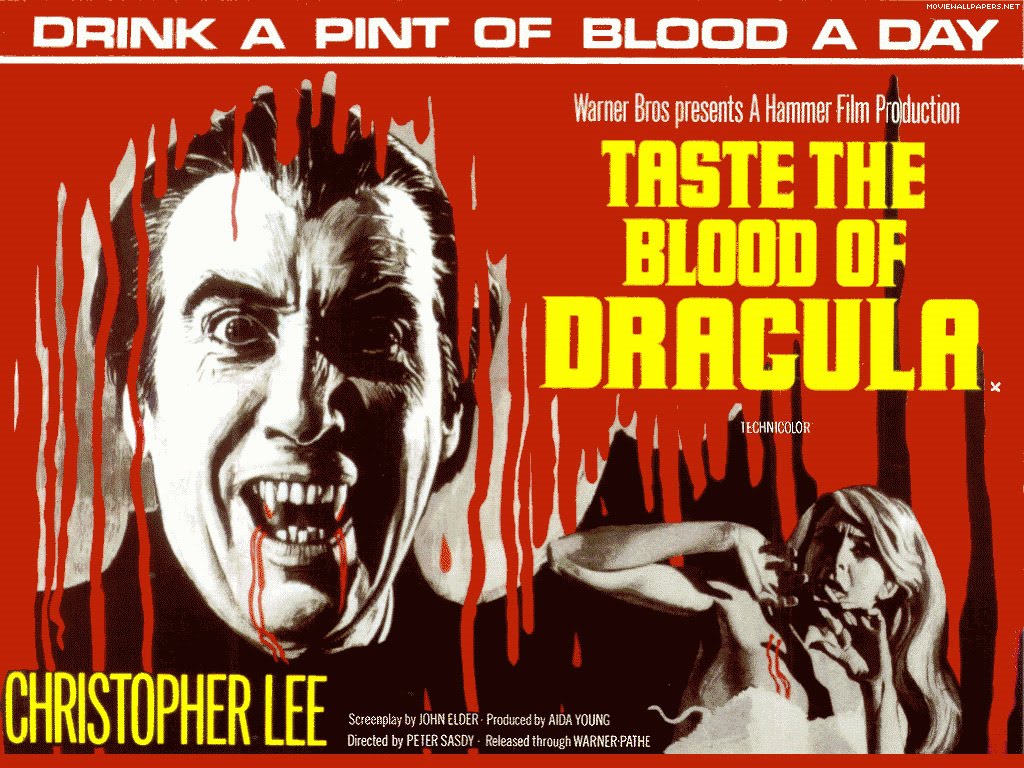

He came to know the two great masters of British horror very well after being taken on by Hammer studios, with whom he made his feature film debut in 1969. Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), was the fifth Hammer film about the Transylvanian count and the fourth to feature Christopher Lee, although Dracula himself has very little screen time. In compensation for some awful dialogue the production values are relatively high, with lavish 19th century sets, shadowy Gothic lighting and some brilliant camera work.

The Stone Tape is probably Sasdy’s finest work and . Shown on BBC2 on Christmas Day 1972 as part of the BBC’s tradition of broadcasting ghost stories at Christmas, Nigel Kneale’s script was unusual in fusing traditional elements – a Victorian mansion haunted by ghostly screams and apparitions – with modern technology. The story focuses on a crew of electrical researchers who have moved into the old house of Taskerlands to concentrate on their new project: to devise an alternative recording medium to magnetic tape, so as to outgain their industrial rivals in Japan. Although the researchers – especially Jill (Jane Asher) – both see and hear apparitions in the house, their sophisticated equipment is unable to record any trace of these – inspiring the team leader Peter Brock (Michael Bryant) to propose a theory: that the supernatural occurrences are actually phenomena that have been recorded by the room itself, and are being replayed through the senses of those present. Does this ‘stone tape’ provide a solution to their technical quest?

The originality of these themes, and the subtle, intelligent way in which they are handled are startling, and it remains a deeply unsettling film even today despite its dated acting style (it comes across as a filmed play, complete with some overtly theatrical performances) and limited effects. The chills come from the sound design rather than the visual effects, as Brock’s team cranks up the noise in order to increase their chances of recording a response from the room’s ‘presence.’

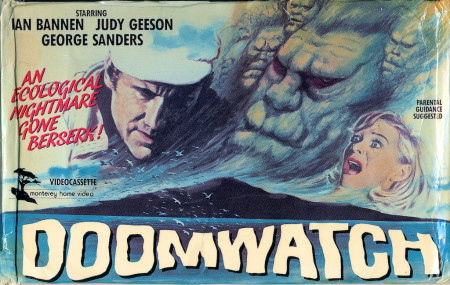

starring Robert Powell, John Paul and Simon Oates that had been inspired by Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass. Again, it was well ahead of its time, tackling the issue of environmental pollution and government cover-ups, albeit with a creepy atmosphere and marketing campaign that would have been more appropriate for a Hammer horrors than for the actual film itself.Both Paul and Oates reprised their roles, with Powell’s place taken by Scottish actor Ian Bannen, and George Sanders playing an admiral. It was filmed in Cornwall, around the area of Polkerris and Polperro.

Some of other Sasdy’s films don’t merit much attention, however, and amongst his worst is Sharon’s Baby (1975), which aimed at replicating the success of Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski, 1968) but fails. Miserably. Attempts to repackage it as I Don’t Want to Be Born, It’s Growing Inside Her and The Monster did not succeed any better. Sasdy even managed to pick up a Razzle Award for Worst Director after The Lonely Lady (1983), an adaptation of Harold Robbins’ best-selling novel that starred multiple Razzle Award winning ‘actress’ Pia Zadora. Of much greater interest was Welcome to Blood City (1977), a science-fiction film that explores the idea of virtual reality over twenty years before The Matrix.

Alongside his film output Sasdy continued doing working for television, including episodes of popular series such as The Return of the Saint (1978-79), Minder (1979) and The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13¾ (1985-87.) His association with Hammer ensured he was kept on board when the studio broke onto the small screen with The Hammer House of Horror (three episodes, 1980) and The Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense (three episodes, 1984.) His last TV production was an Omnibus documentary on another Hungarian director, Alexander Korda, whom Sasdy has often cited as a major inspiration. The disproportionate contribution made by Sasdy’s countrymen to the visual arts has led some to wonder what it is about Hungary that has produced so many brilliant photographers and film directors. But as Korda himself once quipped, ‘It’s not enough to be Hungarian – you must have talent too.’

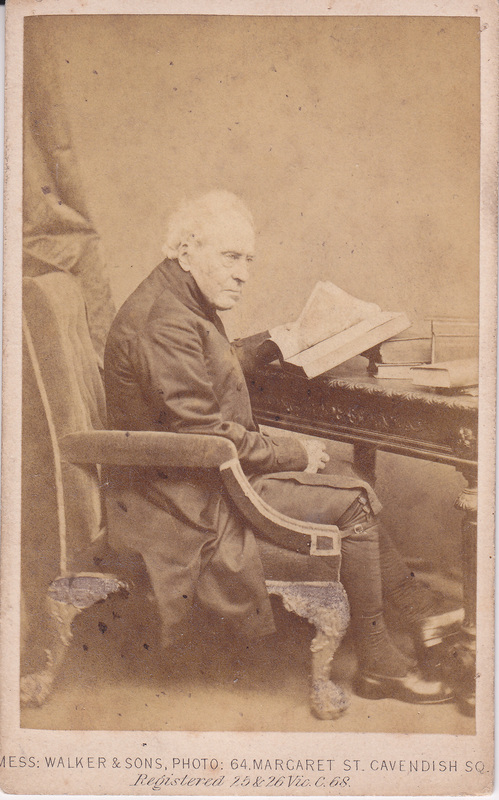

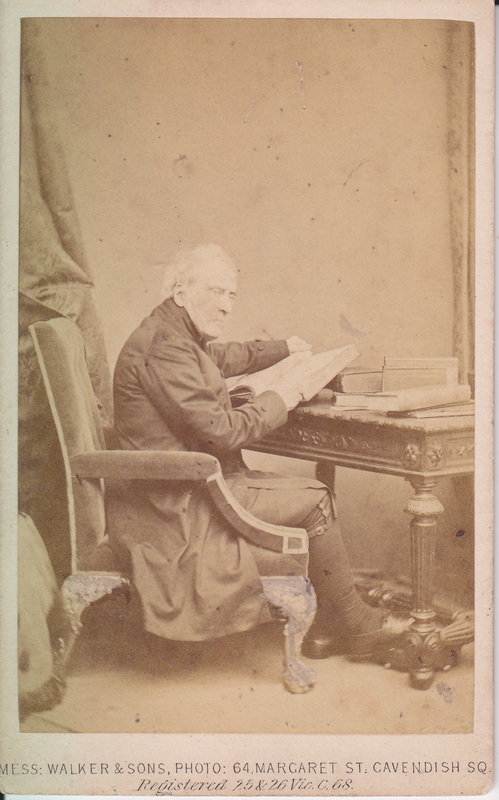

Carte-de-visite of the week #10 Henry PhilLpotts, Bishop of Exeter

Celebrity cards like these were inexpensive to buy – typically between 1/ and 1/6d – and would be sold in stationers shops or other outlets. There was an insatiable market for collecting carte-de-visites of famous people in the 1860s, though one wonders how popular Bishop Phillpotts’ portrait was among collectors, given his unpopularity and fearsome reputation. I remain curious to know more about the person who originally bought this pair of cards. Were they an admirer of the bishop? Did they acquire the cards to go in an album with cdvs of other church dignitaries, or were they collecting cards of local interest to the Exeter area?

Original albums of Victorian cartes-des-visites regularly come up for sale, but often we know little about the way these collections were put together. How often were people buying cards? How much was acquired as part of a clear collecting strategy and how much was picked up on arbitrary impulse, according to what was available or looked appealing? What personal use did the collector make of the images he had acquired? Was the album taken out in the evenings to be pored over as we might do with a glossy ‘coffee-table’ book?

Questions such as these invite comparisons with modern habits of collecting, as well as highlighting the extent to which the meaning and nature of celebrity status has changed over the last 150 years. Some people might be bemused today at the notion of a man like Bishop Phillpotts being regarded as a celebrity, but his contemporaries would be equally baffled, if not more so, at the activities and achievements of those accorded the status of celebrity by the modern media.

Sisters on the screen: 20 films about convent life

To mark today’s screening of Black Narcissus as part of the series of Exeter Screen Talks, I wanted to celebrate twenty films about convent life. The emphasis is on movies that make some serious attempt at portraying religious life, and I have therefore ignored those with fake nuns (A Mule for Sister Sarah (1970) and Più forte sorelle (Renzo Spaziani, 1973) as well as the more lurid examples of the nunsploitation genre (Behind Convent Walls (1978), Sacred Flesh (1999) etc) but at the end of the day the selection is a personal one and is as arbitrary and subjective as can be.

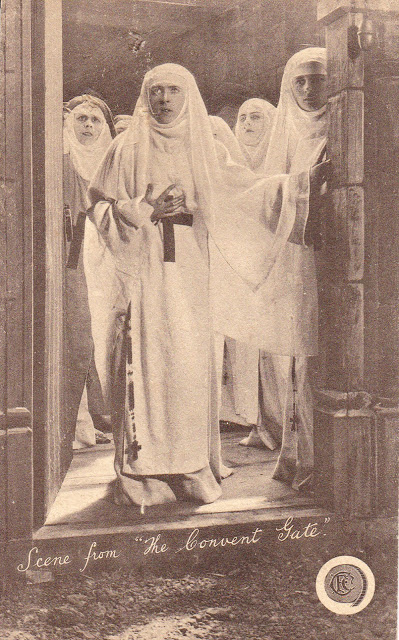

The Convent Gate (Wilfrid Noy, 1913)

Straightaway I’m cheating by writing about a film that I haven’t seen. It’s been estimated that between 75-90% of silent films were destroyed or disappeared, and sadly The Convent Gate was one of them. My interest was piqued when I came across this postcard at a flea market some years ago, and I wrote a little bit about it in a previous post.

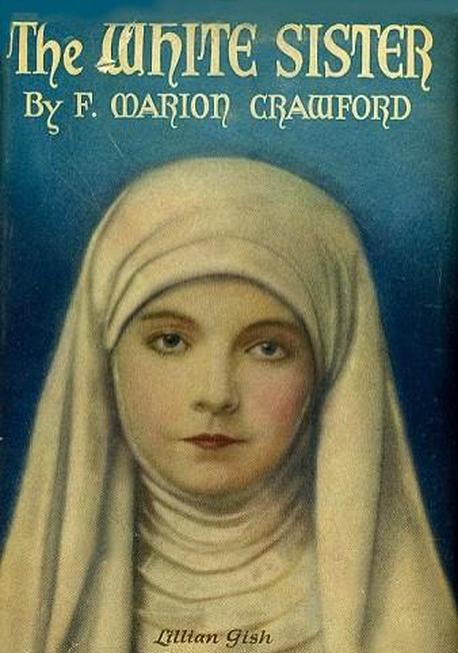

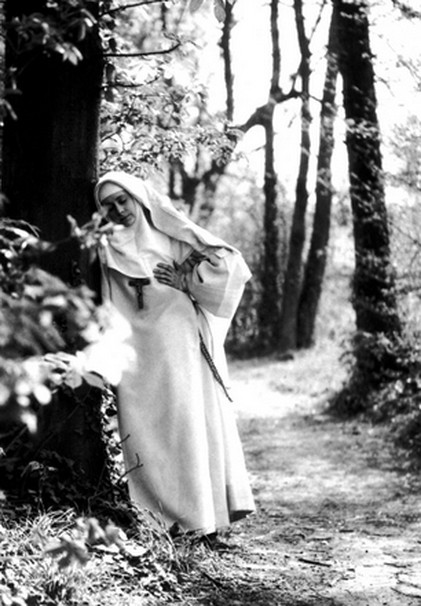

Ten years later Lilian Gish starred in this adaptation of F. Marion Crawford’s 1909 novel The White Sister. It had been filmed already in 1915 with Viola Allen in the title role, as star-crossed Italian lover Angela Chiaromonte who enters religious life after a series of tragic events, plotting and misunderstandings. Ronald Colman played her lover, Captain Giovanni Severini.

The story is set in Italy and ends with the climactic eruption of Vesuvius. While in Sorrento five years ago I came across a street named after Crawford – he moved here in the 1880s and knew the area well.

The White Sister (Victor Fleming, 1933)

In the third screen adaptation of Crawford’s novel Angela was played by Helen Hayes, who was about to make her name playing Mary Queen of Scots and Queen Victoria on Broadway. Colman’s role was taken here by Clark Gable.

Les Anges du Péché (Robert Bresson, 1943)Comparisons are often drawn between the work of Bresson and Bill Douglas, both of whom excelled in the use of poetic imagery with minimal dialogue. Bresson was still finding his style with Les Anges du Péché, his first feature film, made in wartime France in collaboration with Dominican friar Fr. Raymond Bruckberger O.P. and playwright Jean Giraudoux. ‘Angels of Sin’ follows events in a religious community dedicated to rehabilitating women prisoners, but it is easy to see the German occupation of France as influencing the themes of incarceration and vengeance killing.

Bells of Saint Mary’s (Leo McCarey, 1945)

Ingrid Bergman and Bing Crosby star in this drama as Sister Mary Benedict and Father Charles O’ Malley, fighting to save their city school from closure. Both of them get to sing in the movie of course, Bergman singing the traditional Swedish folksong Varvindar Friska (Spring Breezes) and Crosby crooning the title song (along with a choir of nuns) and others. The movie is used in the film The Magdalene Sisters (Peter Mullan, 2002) with bitter irony – the sweet nuns of the 1945 film contrasting harshly with the cruel, somewhat cartoonish villains of Mullan’s tale.

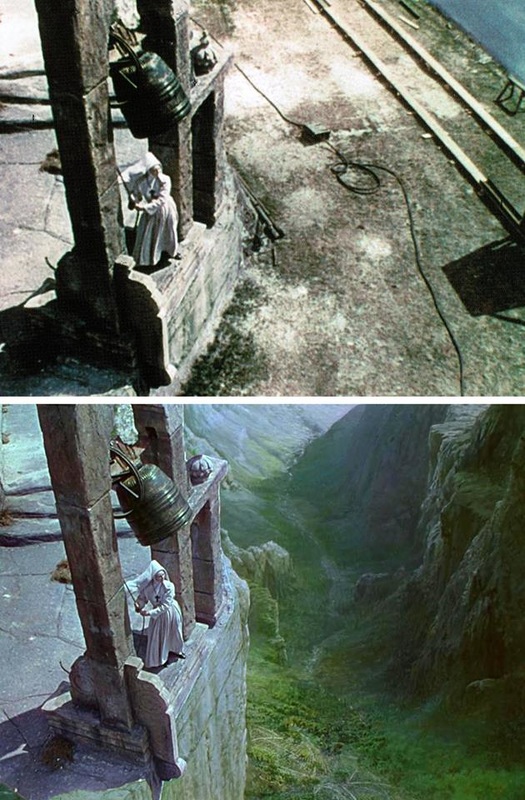

One of my favourite films of all time, and my strongest recommendation of all those listed here, Black Narcissus is based on Rumer Godden’s 1939 novel and tells the story of a community of nuns opening a convent in the Indian Himalayas. As with so much of Powell and Pressburger’s work, the film is imbued with a strong sense of place and an awareness of the effect of location on human behaviour: the lush sensuality of the landscape (filmed in vibrant Technicolor by Jack Cardiff) and the erotic history of the convent building (a former seraglio) seem to draw out the emotional tensions and desires of the nuns – in particular Sister Ruth (below.)

The magnificent cast also includes Deborah Kerr, Flora Robson, Jean Simmons, Esmond Knight and a surly, swaggering David Farrar.

Another tale of nuns moving into an unfamiliar location, but very different in tone, Come to the Stable starred Loretta Young and Celeste Holm as two French nuns trying to establish a foundation in Bethlehem, Connecticut. Unlike the plot of The Bells of St Mary’s the nuns don’t resort to trickery to achieve their goals…

Thunder on the Hill (Douglas Sirk, 1951)

This who-dunnit is set in a storm-lashed Norfolk convent, where convicted murderess Valerie Carns (Ann Blythe) gets marooned by the weather while en route to the gallows. (Ruth Ellis, the last woman hanged in Britain, died four years later, in 1955.) Claudette Colbert plays Sister Mary, a young nun who begins to have doubts about Valerie’s guilt – setting her on course to clash with the Mother Superior (Gladys Cooper.)

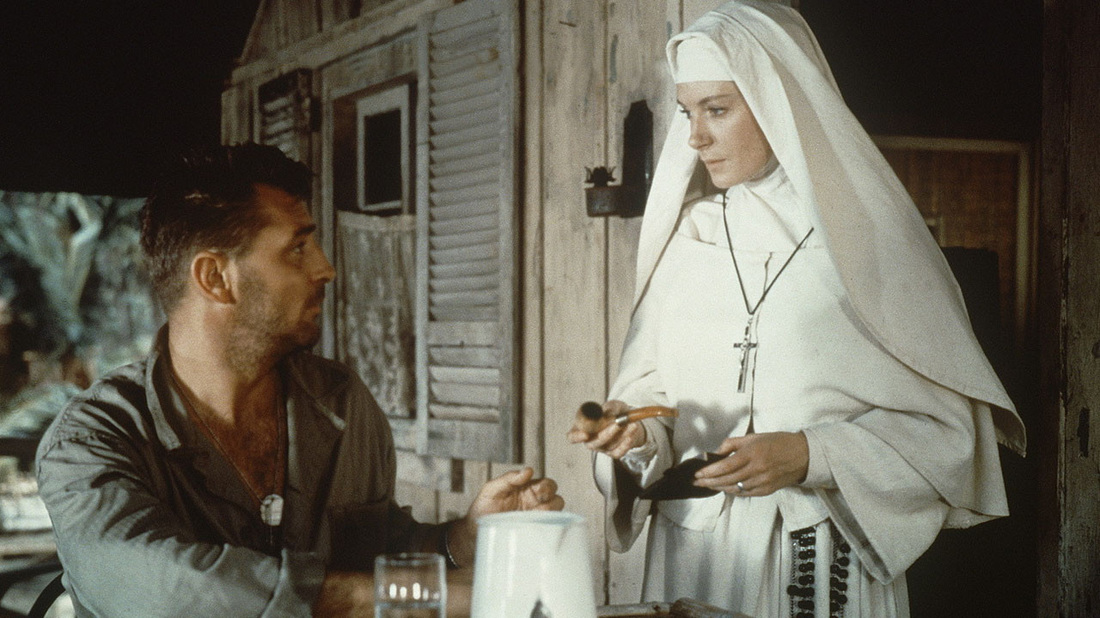

Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (John Huston, 1957)

Having played the Sister Superior in Black Narcissus, Deborah Kerr was demoted to the status of a novice in this film, in which she is stranded together with US marine Robert Mitchum on a Pacific island during WWII. They have to deal with lack of food, fever, Japanese soldiers and – of course – each other, while waiting to be rescued. Both stars give tremendous performances, while the exotic location (much of it was filmed in Tobago) provides a lush backdrop to the poignancy and drama of their situation.

The Nun’s Story (Fred Zinnemann, 1959)

Based on Kathryn Hulme’s 1956 novel, The Nun’s Story follows Sister Luke (Audrey Hepburn) as she struggles to deal with inner conflict as a medical nun working in Africa. As with The White Sister and Black Narcissus, there are hints of an unresolved romance haunting her decision to enter the convent, but Sister Luke also has to deal with issues regarding obedience and her duties towards her family and homeland after the Nazis invade Belgium while she is working in Africa. It’s one of the best films for a serious exploration of the real issues involved in taking the veil.

(Philippe Agostini, 1960) This was another wartime project of Fr Bruckberger O.P., based on Gertrud le Fort’s novel about a community of Carmelite nuns who were martyred at Compiegne in 1789 during the French Revolution. George Bernanos wrote additional dialogue – much of which was later dropped – and stage and opera versions were produced before the screenplay finally made it to the screen. Jeanne Moreau played Mère Marie de l’Incarnation.

(Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1961) Based on the same story about the possessed nuns of Loudun that inspired Ken Russell’s film ten years later, Mother Joan of the Angels is much less well known: this is a shame, as it’s an absolute masterpiece, subtle in all the places where Russell is extravagant, yet containing a wealth of stark, stunning imagery and poetic visuals.

Lilies of the Field (Ralph Nelson, 1963)

This film provided Sidney Poitier with his first Oscar, playing wandering handyman Homer Smith who finds work (but no wages) helping out a struggling community of nuns from German and Eastern Europe. The title of the film is taken from Matthew 6:28-30, which Mother Maria (Lilia Skala) quotes in response to Homer’s request to be paid.

Maria von Trapp’s memoir The Story of the Trapp Family Singers provided the basis for a Rodgers & Hammerstein musical which was in turn adapted for the screen by 20th Century Fox. Julie Andrews played Maria, a novice nun who leaves the convent for a while to work as a governess to an Austrian family of seven children, and ends up leaving religious life and marrying their widowed father. Some of the exterior scenes were shot at the convent of Nonnberg in Salzburg.

The Nun (Jacques Rivette, 1966)

Denis Diderot’s novel La Religieuse, published in 1796, offers a profound critique not only of religious life and Catholicism but also of the constraints placed upon women in 18th century society. Diderot’s simple tale recounts the sufferings of a young girl, Suzanne Simonin, who is forced into the convent by her family. French New Wave director Jacques Rivette adapted the novel for the stage before revising it for the screen, in both versions casting Jean Luc Godard’s then-wife Anna Karina as Suzanne. It remains quite stagey, with its slow pace and unadorned style, but it’s deeply moving and heartbreaking in its depiction of Suzanne’s ordeals as she experiences religious life under three Mother Superiors – the kindly Madame de Moni (Micheline Presle), cruel Sister Sainte-Christine (Francine Berge) and the ardent Madame de Chelles (Liselotte Pulver.) The film was remade by Guillaume Nicloux in 2013 with Isabelle Huppert playing Suzanne.

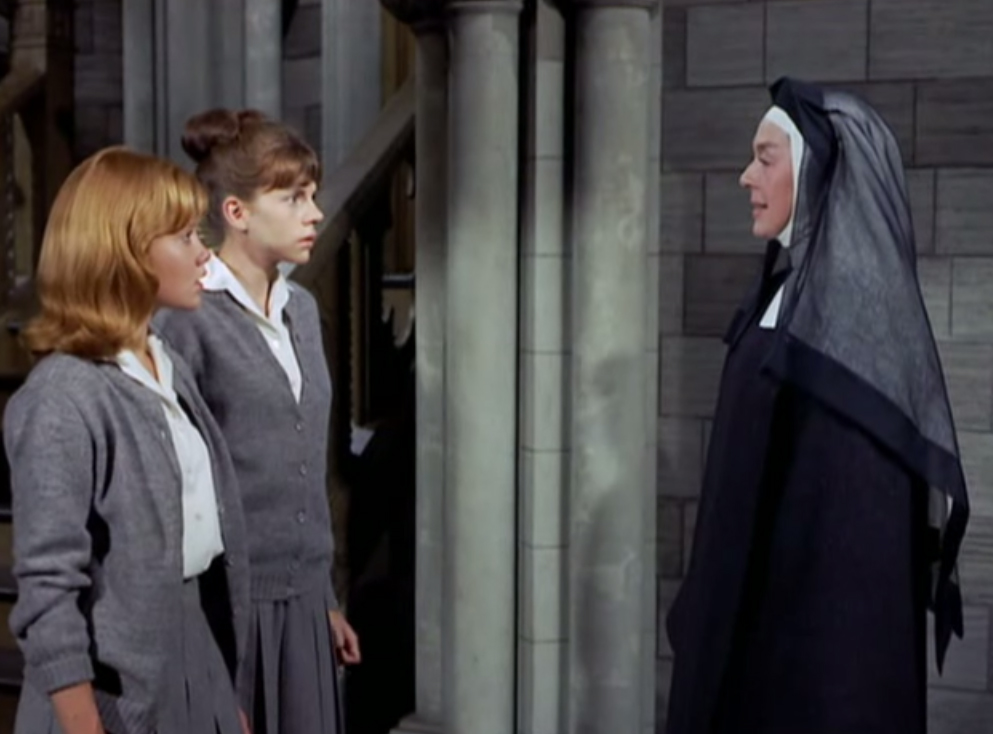

The Trouble with Angels (Ida Lupino, 1966)

Returning to the present day and a lighter vein, The Trouble with Angels was set in an American convent school where rebellious pupils Hayley Mills and June Harding try to outwit the Mother Superior (Rosalind Russell), only to find that they underestimate the nun’s wisdom and wiles. The success of the film inspired a rather lacklustre sequel, Where Angels Go, Trouble Follows (James Neilson, 1968.)

‘The Singing Nun’ was the popular name given to Sister Luc-Gabrielle O.P., also known as Jeanne Deckers (1933-85), a Dominican nun from Belgium who released several records including the No.1 single ‘Dominique’ (1963.) The movie is a sweetly fictionalised portrait of Deckers, whose life subsequently took a tragic dive downwards into depression, drug abuse and suicide.

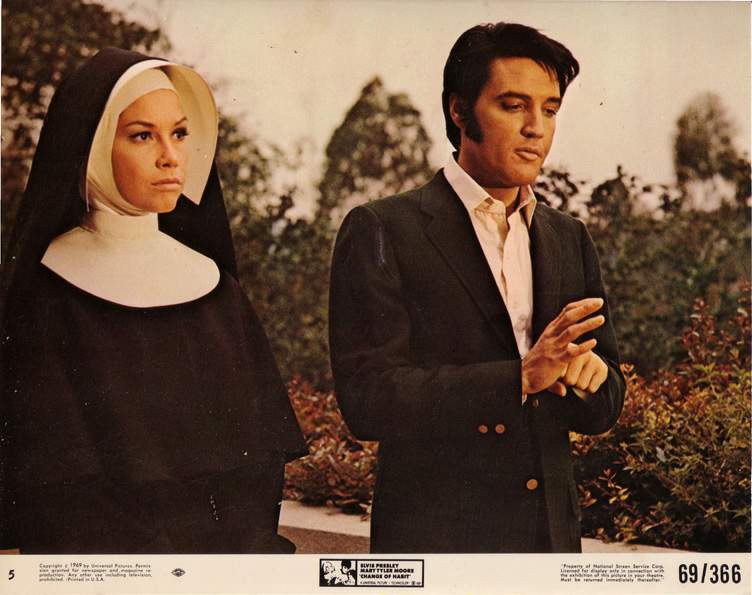

Change of Habit (William Graham, 1969)

Elvis Presley’s final fictional movie role saw him play a doctor in a run-down area who is unaware that three co-workers – Michelle Gallagher (Mary Tyler Moore), Irene (Barbara McNair) and Barbara (Jane Elliott) are in fact nuns who have shed their habits in order to gain the trust of the parishioners they are trying to help. The movie, as one would expect, contains romantic entanglements and lots of Elvis songs.

As a by-the-by, it is perhaps worth mentioning that another of Elvis Presley’s co-stars, Dolores Hart – who played opposite ‘The King’ in Lovin’ You (1957) and King Creole (1958) – entered a real-life convent in 1963 and later became the Prioress of Regina Laudis Priory in Connecticut.

The Devils (Ken Russell, 1971)

It’s been over forty years since the release of The Devils but Ken Russell’s extraordinary and disturbing work has retained its reputation as one of the most shocking movies ever made in Britain. The scenes of orgiastic violence are graphic and unrelenting, but shot with the high command of visual aesthetics that one would expect from production designer Derek Jarman. Although Vanessa Redgrave played Mother Jeanne of the Angels, the role had been originally offered to Glenda Jackson. However, after playing the female leads in Russell’s Women in Love (1969) and The Music Lovers (1970), a third erotically-charged performance might have been excessive (even for them.) As a representation of convent life The Devils cannot evade the charge of sensationalism – it’s a orgy of Grand Guignol grotesquerie and Gothic horror – but it explores aspects of religious psychology and the interior life that are barely touched by the other films listed here. Go there if you dare.

Nasty Habits (Michael Lindsay-Hogg, 1977)

It wasn’t long Jackson got another chance at playing a nun, and this time she accepted the offer: Nasty Habits is based on Muriel Spark’s novel The Abbess of Crewe: A Modern Morality Tale (1974), which took the then highly-topical story of the Watergate scandal (1972-74) and transposed its component parts into a Benedictine convent where a power-hungry nun is plotting to fix her election as abbess. The film version shifts the setting from Crewe to Philadelphia and assembled a star-studded cast that included Edith Evans as the old Abbess Hildegard whose death leaves a power-vacuum, Glenda Jackson as the ambitious Sister Alexandra (i.e. Nixon) and Geraldine Page and Anne Jackson as her accomplices Sisters Walburga and Mildred, who break into the sewing basket of her rival Sister Felicity (Susan Penhaligon) in order to steal a cache of love letters. Allegations of bugging and bribery lead to Vatican involvement, and those familiar with the Watergate story will enjoy identifying the characters and events being parodied.

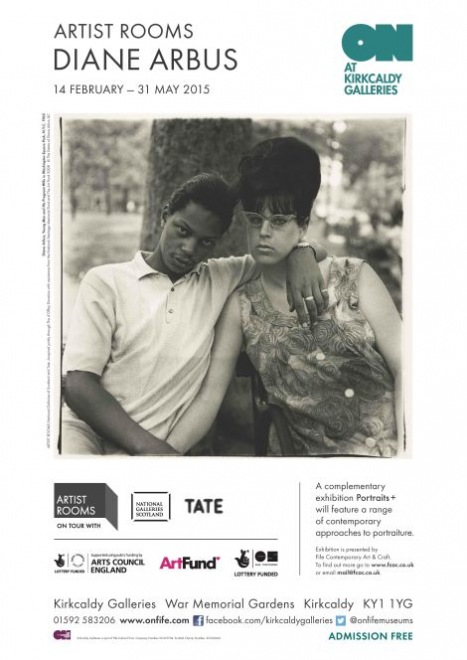

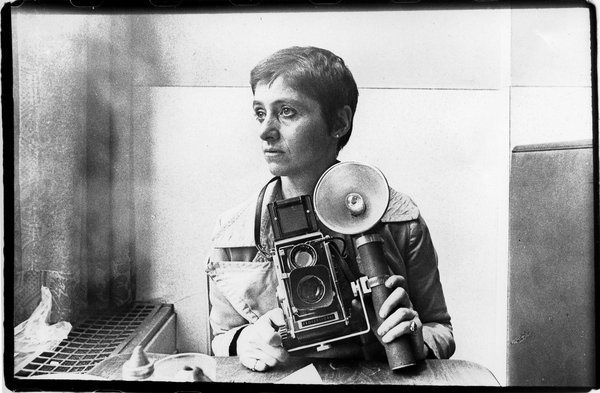

Diane Arbus in Kirkcaldy

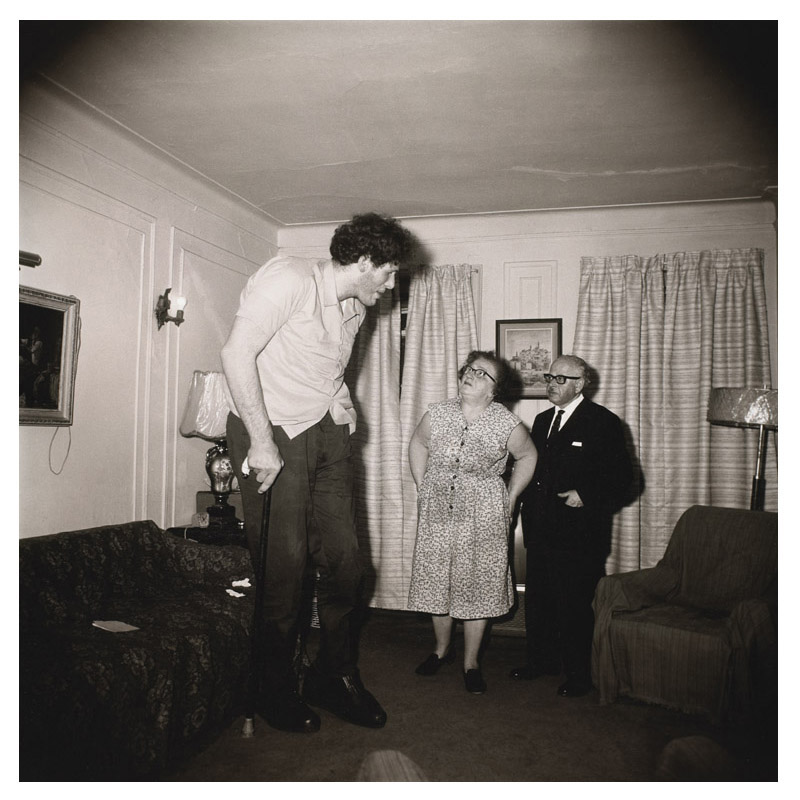

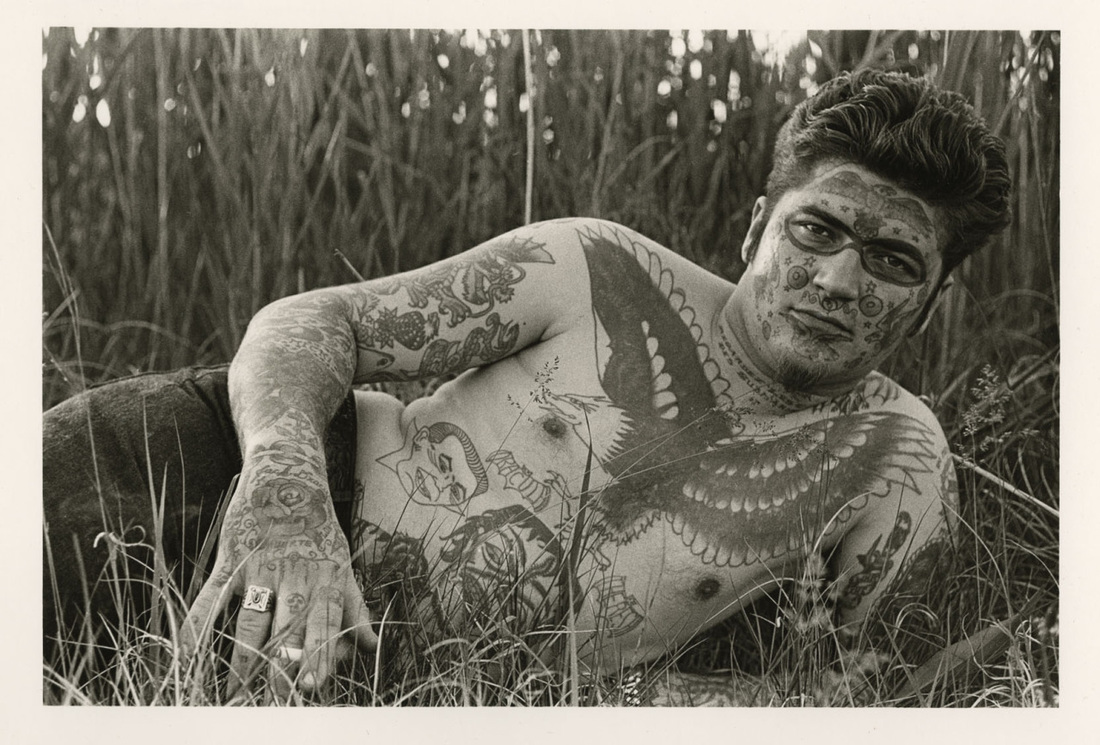

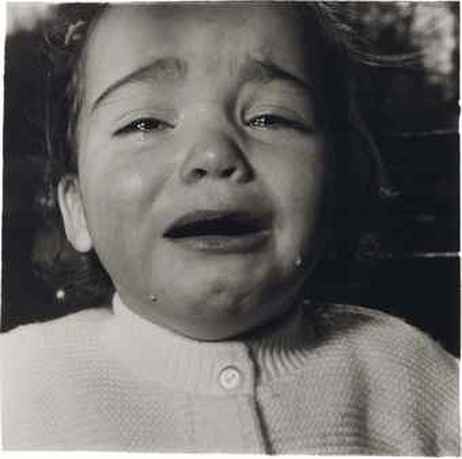

The image above, like the majority of Arbus portraits, is taken face-on, so that the viewer has a direct confrontation with the subject of the photograph. It is this aspect of her work, as much as the content matter, that is so unsettling. There is no opportunity to avert the eye, to focus on another portion of the image and try to alter the perspective. Unlike her early fashion shoots, these are not contrived studio sessions but are taken in the sitters’ own homes, institutions or workplaces, so that it is we who find ourselves in unfamiliar settings, alienated, confronted with people and places that may make us uncomfortable. The fact that many of her sitters appear quite at ease with their physical or mental awkwardness, or even proud of their disfigurements, challenges us to identify who it is that has the real problem.

However, not all the sitters appear comfortable with being photographed, and in the case of those with severe mental disabilities it is evident that their consent was never – and could never – be obtained. The photographer’s troubled life – after several bouts of depression Arbus committed suicide at the age of 48 – invites connections with these images of loneliness, marginalisation and suffering. Does evidence of her own unhappiness demonstrate a degree of affinity or sympathy with those she photographed? There is an honesty about her photography that undermines accusations of voyeurism or exploitation, although such charges have been made. Influential critic Susan Sontag expressed her unease about Arbus’s work in her 1973 New York Review of Books article ‘Freak Show’, which was later revised to form the central essay in On Photography (1977.) Surprisingly, for such a respected writer, Sontag never really strikes home with any critical insight about Arbus’s work. The essay is effective in articulating Sontag’s negative response, but reveals little about the photographs themselves. Her main charge – that of a lack of compassion – has ‘stuck’ nonetheless, and it is no simple matter to dismiss.

One might argue that developing a ‘lack of compassion’ is an occupational hazard for any photographer working in the documentary tradition, particularly those commissioned to record scenes of suffering in war zones or disaster areas. Maintaining a high degree of detachment is essential for professional standards: but where does one draw the line? And does the practice of enforcing such discipline not run a risk of psychological self-harm? The story of Kevin Carter (1960-94) remains a salutary warning; the life, work and death of the South African photographer was dramatised in the film The Bang-Bang Club (Steven Silver, 2010) and inspired Alfredo Jaar’s unbearably moving art-installation The Sound of Silence (2006.)

Diane Arbus’s life has also been depicted on the big screen, providing the inspiration for the film Fur (2006) directed by Steven Shainberg. Like his earlier Secretary (2002) it is an audacious portrayal of a woman’s unorthodox desires, but as a portrait of Arbus it is unsatisfactory. Those wanting to know more about her should begin by studying her photographs – and for anyone in the region of Kirkcaldy, their exhibition remains open for another month, until the end of May.