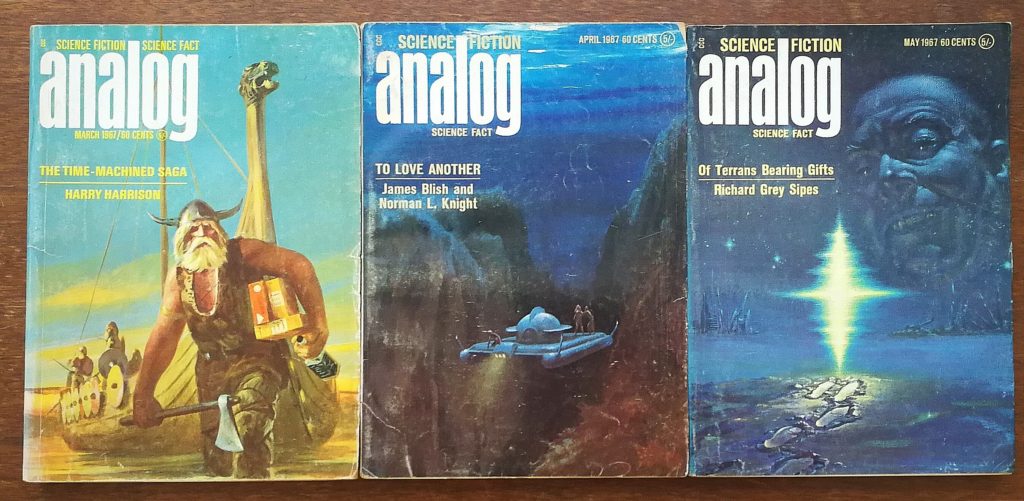

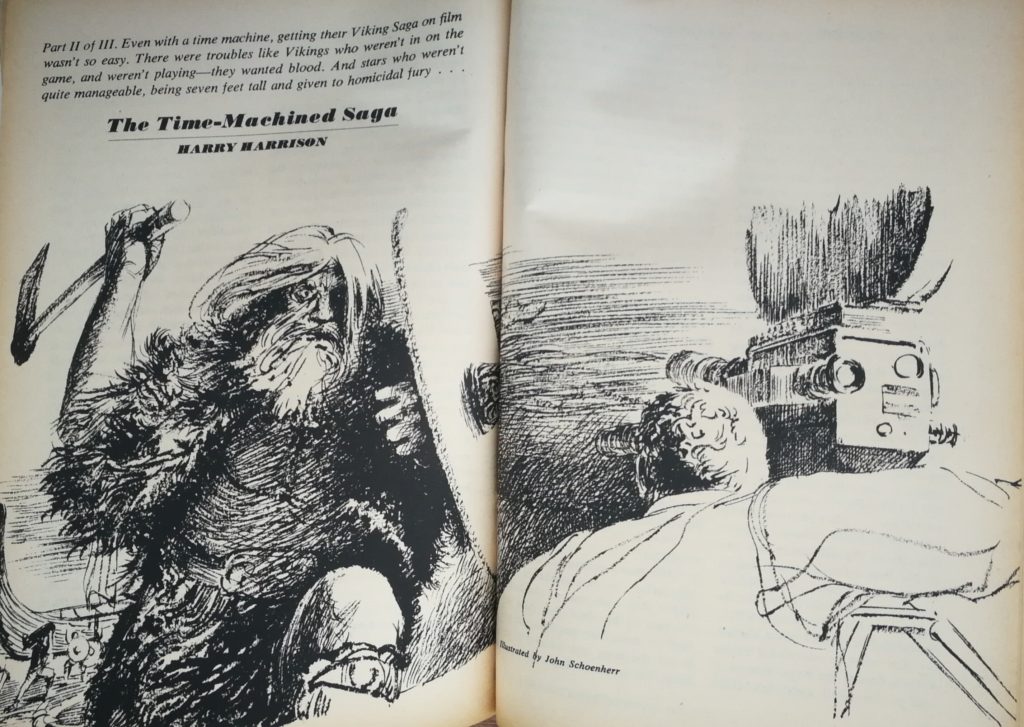

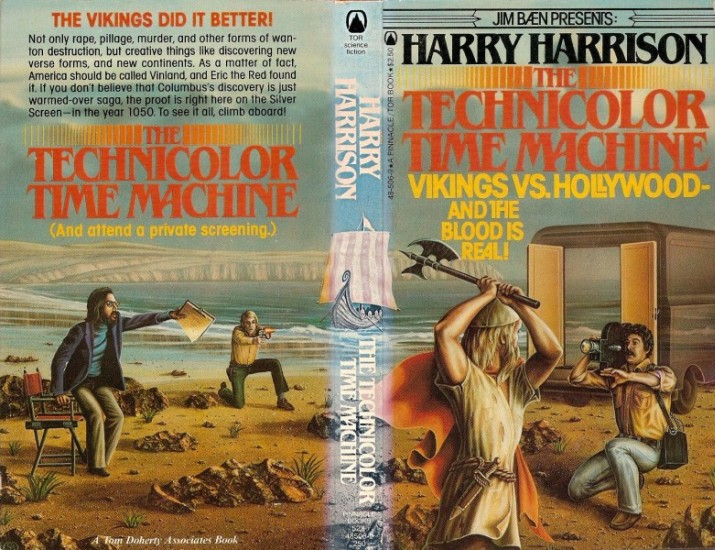

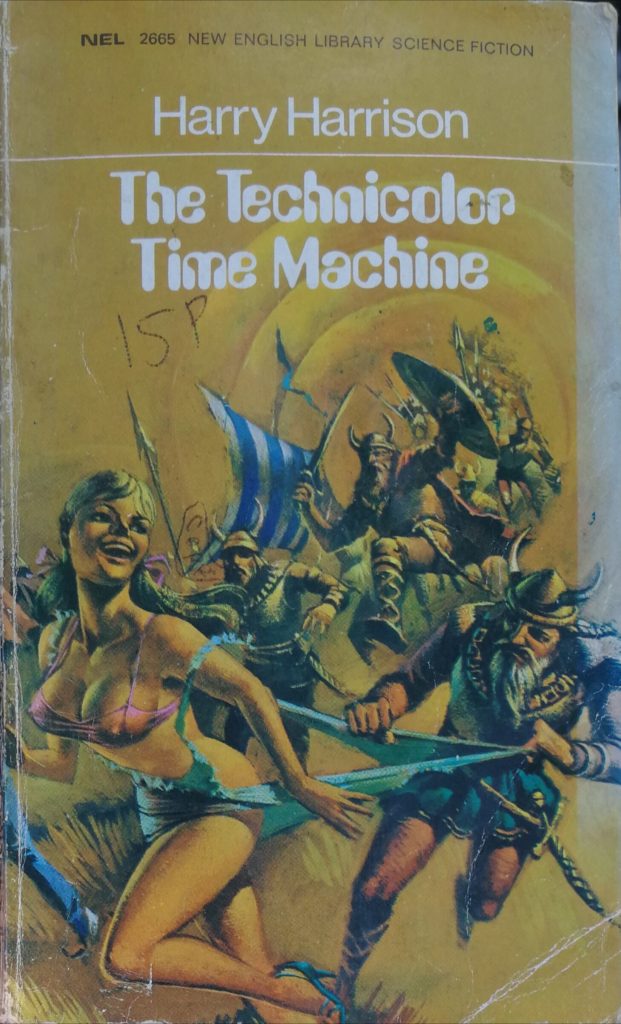

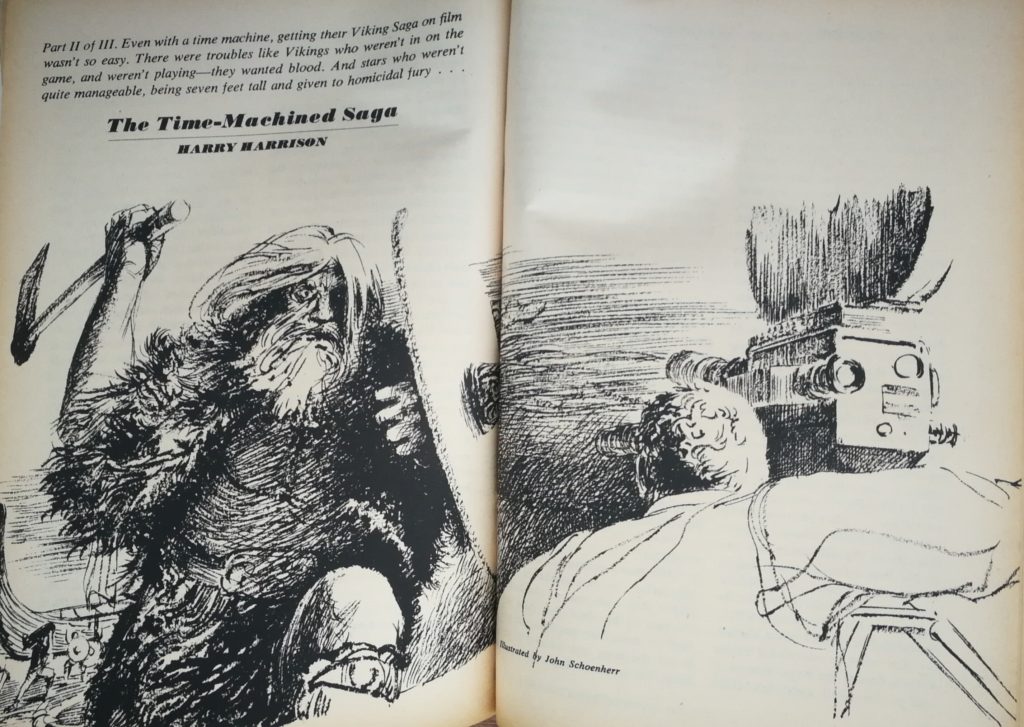

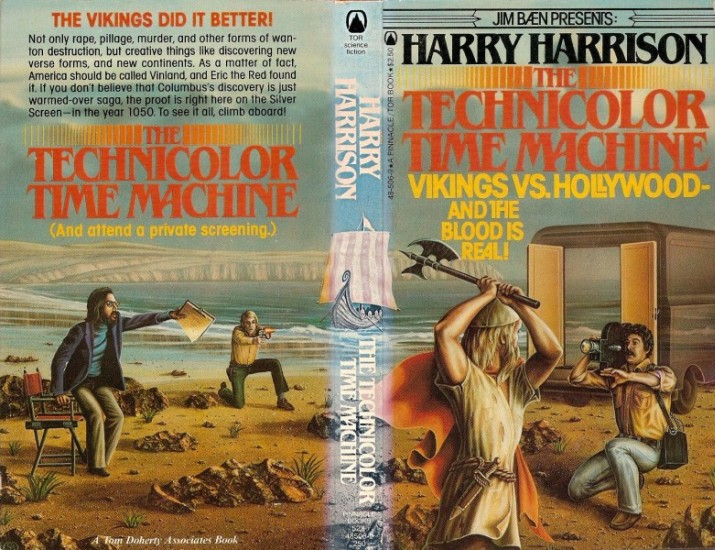

At first sight The Technicolor Time Machine might seem an odd choice for a classic film reading. After all, author Harry Harrison (1925-2012) was a doyen of the science-fiction community, beginning his career as an illustrator for the EC Comics titles Weird Fantasy and Weird Science before going on to write and edit numerous science-fiction stories, novels and anthologies. This book first appeared as a three-part serialised story in Analog Science Fiction and Fact (March–May 1967 issues) as ‘The Time Machined Saga’.

The original magazines in which the story first appeared, along with artwork by John Schoenherr

While there’s no denying its credentials as a piece of science-fiction, The Technicolor Time Machine can also be read as a satire of the film industry during Hollywood’s Golden Era, and indeed it was those elements of the book that I found most enjoyable.

At this point a quick recap of the plot would probably be in order. The story begins at the offices of Climactic Studios, where hack director Barney Hendrickson and corrupt studio owner L. M. Greenspan are facing financial ruin within a matter of days.

Only a miracle can save the studio, and this miracle comes in the person of eccentric scientist Professor Hewett, who claims to have built a time machine – the vremeatron – that would enable Hendrickson to go back in time and make a historical movie without the need to pay for any set construction or extras. This is the essential ‘gimmick’ of the novel, but as the story progresses, the notion of time travel is exploited more and more as a strategy for smoothing out difficulties in the film’s production.

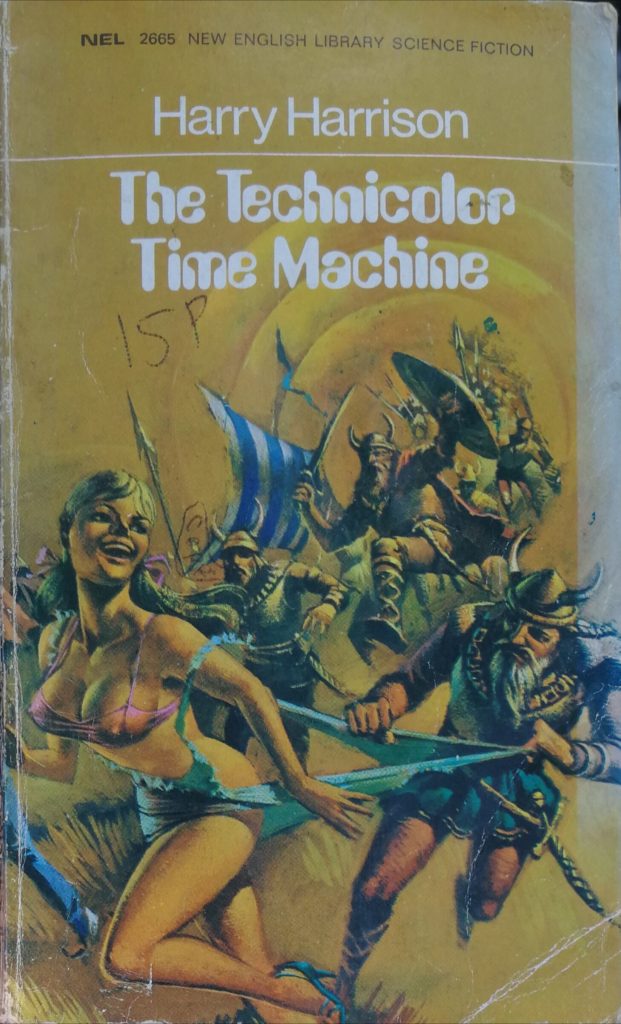

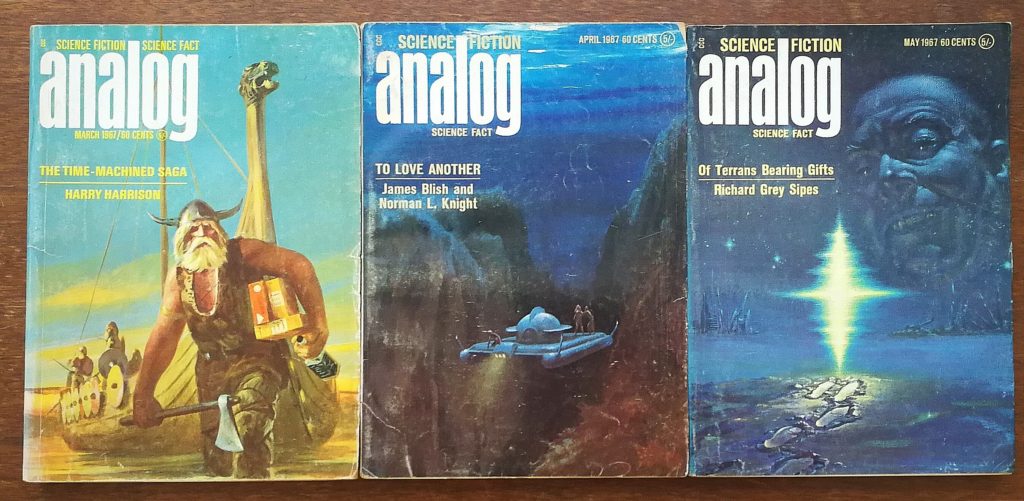

In the first instance of this, to buy them some time, the Chinese-American scriptwriter Charley Chang is sent back to the Precambrian Era where he works away on a remote island in solitude for a month, returning to the present day with a script entitled Viking Columbus about the founding of the Viking settlement of Vinland in North America. Having obtained a script, cast and crew travel back to the Orkney Islands ca.1003 AD where they hire a real-life Viking – and larger than life character – named Ottar to be their guide and Norse interpreter. Ottar eventually takes over the leading role when Hendrickson’s vain star actor, Ruf Hawk, injures himself during filming – a replacement that has unexpected consequences for the leading lady, the voluptuous Slithey Tove.

Slithey Tove as imagined by artist Bruce Pennington on the front cover of my copy of the novel

As befits a story originally published in a science-fiction magazine, there are some serious efforts to get to grips with the complex mechanisms of time travel, but these are not pursued for their own sake – rather, they form an important part of the plot as Hendrickson struggles to meet the deadlines and needs to find ever-more desperate ways to save time.

Issues about the saving, passing and good use of time are at the heart of the story, which gives the author ample scope to lampoon Hollywood’s attitude toward the past. Jokes are made not only about Hollywood’s disregard for historical accuracy, but also the general illiteracy in matters of history and culture: ‘Eric the Red? You want us to get blacklisted with a commie picture’? Filmmakers are portrayed as mercenary individuals, churning out films with titles such as The Creature’s Son Marries the Thing’s Daughter, The Pfc. from Brooklyn and Teen-age Beatniks’ Hophead Rumble, which lie just on the borderline between absurdity and near-credibility. Despite the strongly satirical tone there are some nice little touches that make the cinematic setting of the story almost believable. The camera man Gino Cappo uses an 8mm Bolex camera to try out some angles, and later expresses his concerns about light exposure – ‘I should have loaded this up with Tri-X. It’s five in the afternoon’ – before offering his thoughts on the future of the movies. ‘You haven’t heard the last of Cinecitta yet, Mr Hendrickson, not by a long shot. The new realism came out of Italy after the war, then the kitchen-sink film that the British picked up. But you’ll see, Rome ain’t dead yet..’

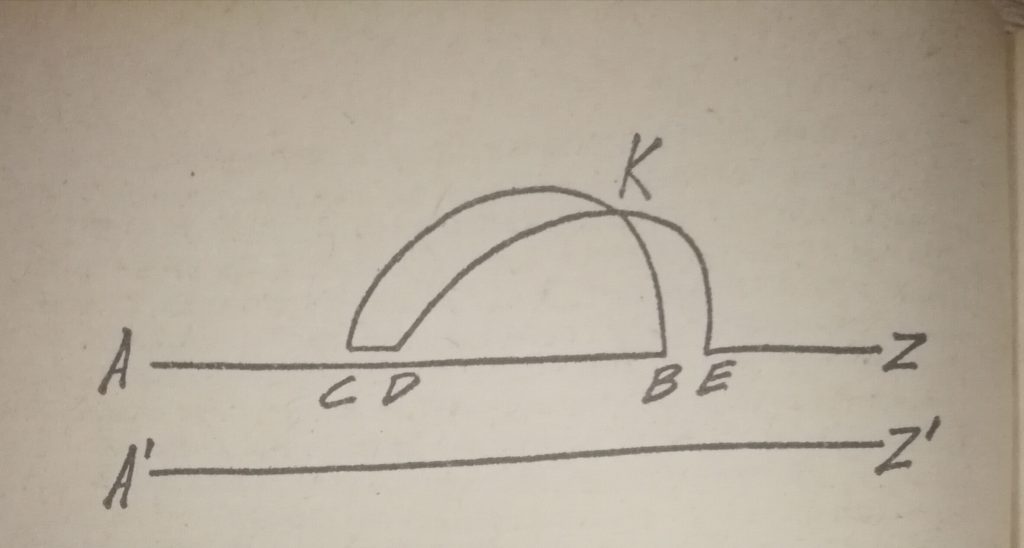

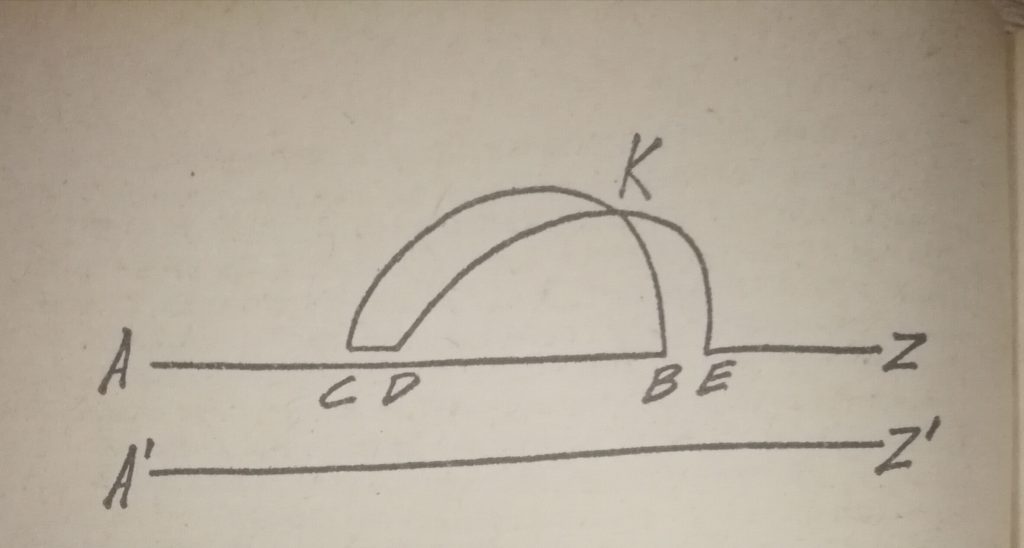

As events in Vinland take a turn for the worse, death – in a very real sense – threatens not only the Vikings but also the 1960s film crew. By the end of the book it becomes clear that – even if they succeed in eluding arrows, axes, spears or drowning – there will be serious consequences from their reckless time travel. As Professor Hewett explains, with the help of a handy diagram (in which A1-Z1 is the world time line, with A1 the past and Z1 the future, and A-Z is the timeline navigated by the film crew):

The film-makers must go back in time at B, arrive at C, stay till D and then return to E: the graph must always read ‘B-E’, never ‘E-B’, otherwise K – ‘the interchange of energy point, where the scales of time are balanced’ – would not exist. Readers who are reminded of the prohibition in Ghostbusters – ‘never cross the streams’ – will probably also recall the dire warnings in Back to the Future about what might happen if one meddles with the past. There will no spoilers here, and anyone wishing to find out what happens to Barney, Slithey and co. will have to read The Technicolor Time Machine to find out. Hollywood has been the setting for countless novels and the subject of many a satire, but combining these with a well-crafted science fiction tale provides a rare treat, even if the tone may at times be too whimsical for certain tastes. A BBC radio adaptation was broadcast in 1981 as part of the Saturday Night Theatre series, and there were rumours some twenty years ago that Mel Gibson had bought the film rights – although whether he is the best person to be at the helm of such a project is open to question. In the meantime, the clever concept of The Technicolor Time Machine has inspired a great number of book illustrators and the cover art for the myriad paperback editions are well worth exploring.

This post was written as part of the 2018 #classicfilmreading challenge.

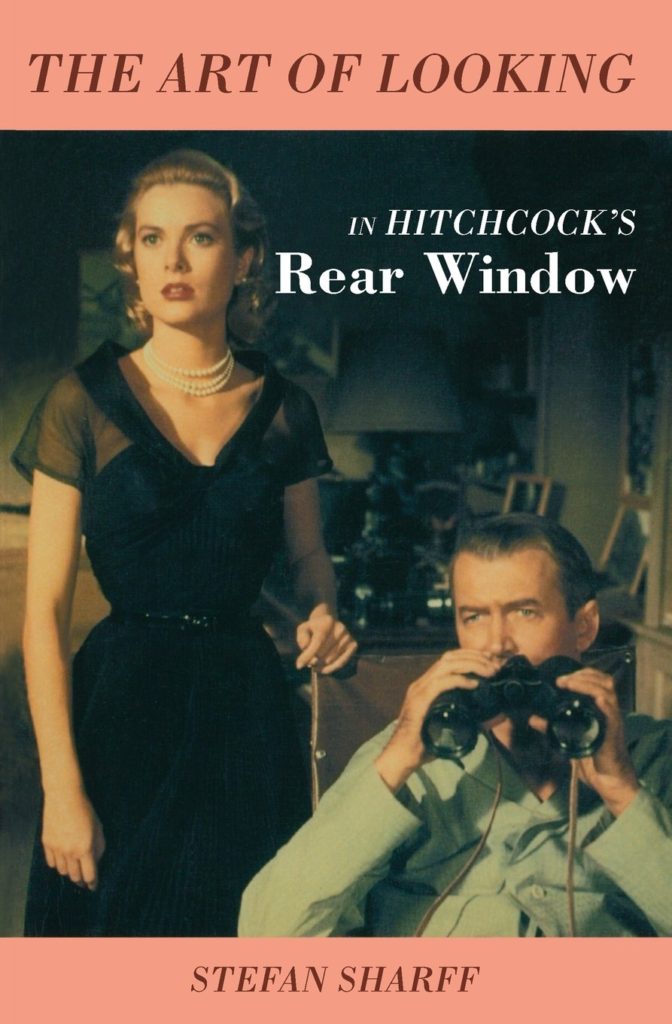

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window