One may be sure that when Gibbon wrote sarcastically of ‘the monks of Magdalen’ he never envisaged any real association between his Oxford college and those men who take religious vows according to the Rule of St Benedict. Yet just over one hundred years after Gibbon’s death a monastery was founded in Oxford itself, and this little Benedictine house of studies was known as Hunter-Blair Hall after the name of its Master. Oswald Hunter-Blair was not only a monk and a graduate of Magdalen, he was also a baronet, would later become an abbot, and stands out as one of the most colourful Catholic converts of his time.

David Hunter-Blair was born on the 30th September 1853, the eldest of thirteen children (nine sons and four daughters) of Sir Edward Hunter-Blair (1818-96), 4th Baronet of Dunskey, and Elizabeth Wauchope. Dunskey Castle is in Wigtownshire on the southwest coast of Scotland. His mother’s family, the Wauchopes of Niddrie, had remained Catholic for almost two centuries after the Reformation before going over to the Scottish Episcopalian Church in 1750, but although all his siblings were baptised by Episcopalian clergy the future Benedictine abbot received the sacrament from the Presbyterian minister of Portpatrick.

In 1854 his father’s elder brother was killed at the Battle of Inkerman and Sir Edward inherited the baronetcy and estates. According to the arrangements of the settlement he was obliged to divest himself of the estate of Dunskey if he was to possess Blairquhan. His eldest son David therefore became the laird of Dunskey at the age of four.

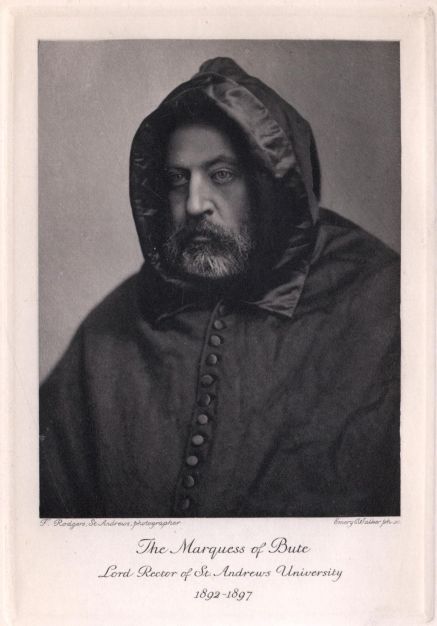

In the summer of 1863 the family left the country for Spa in Belgium where they were to live for over a year before moving on to Boulogne. David returned to Britain in January 1864 to attend prep school at May Place, Malvern Wells – a select establishment where almost every boy had a Duke or a Marquis for a father. From here he proceeded to the Upper IVth form at Eton. He was a fifteen-year old pupil here in 1868 when he heard the sensational news of the conversion to Catholicism of the 3rd Marquess of Bute. A favourite uncle of his, Colonel David Hunter-Blair (1827-69) took the same step the following year. His own mind was already intrigued by the Catholic past through reading Walter Scott’s novels and he noted in Eton ‘the aura of Catholicism which still hung faintly about her venerable halls and cloisters.’

Hunter-Blair went up to Oxford and studied at Magdalen College from January 1872 to December 1876. For the winter term of 1875 he received permission to study music in Leipzig under Karl Reinecke (1824-1910), the pianist and conductor of the Gewendhaus and also Professor at the Leipzig Conservatorium.

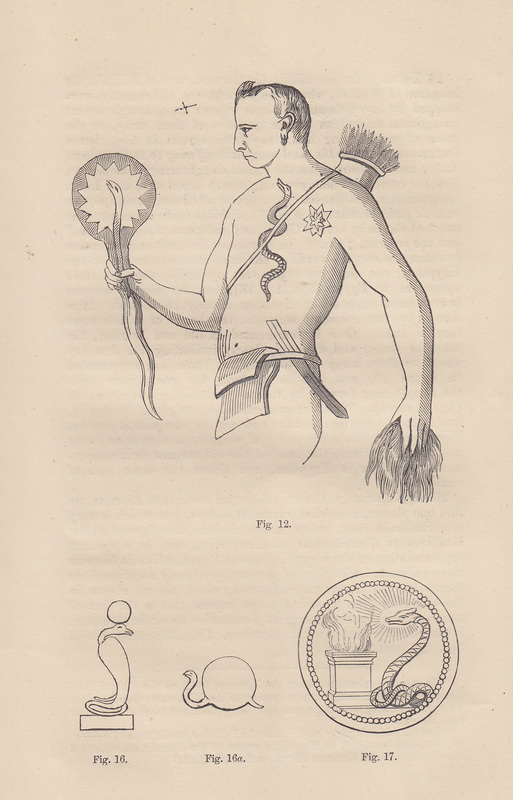

By this time the religious question was clear in his mind. With his fellow student Harold Willoughby he left Germany for Rome, arriving in time to see Manning receive his cardinal’s hat on the 15th March. Ten days later on Maundy Thursday, 25th March, 1875, he was received into the Catholic Church by Fr Edward Douglas C.SS.R. in the Redemptorist house on the Esquiline Hill. Fr Douglas (1819-98) was a kinsman of the Marquis of Queensberry and himself a convert. From Rome it was back to Oxford in April to begin the summer term: unlike Gibbon he was not forced to leave because of his apostasy. Instead of the High Anglican services of old he now walked over Magdalen Bridge each Sunday to attend Mass at the dingy St Clement’s Catholic Church. He also renounced membership of the Masonic Lodge, regarding this as incompatible with Catholicism. A number of students were especially interested in Freemasonry at this time because Prince Leopold – Queen Victoria’s youngest son and then a commoner at Christ Church – was also Grand Master of the Freemasons.

His friend and fellow-student Oscar Wilde had been initiated into the Masons just weeks before Hunter-Blair became a Catholic. Filled with a new convert’s zeal Hunter-Blair was determined that Wilde would follow him; the poet’s fascination with the Catholic Church was then at its peak. Wilde visited Italy in the summer of 1875 with staunch Protestants Professor Mahaffy and William Goulding, and on the 15th June he wrote the poem ‘San Miniato’ which was published in the Dublin University Magazine the following March. He had to break off the trip at Verona, leaving his friends to go ahead to Rome, in consequence of which he composed ‘Rome Unvisited’. Hunter-Blair thought highly of this poem, as did another Oxford convert, John Henry Newman, and when his friend returned for the autumn term he sought to carry Wilde over the threshold. Together they attended the opening of St Aloysius’ Church on 23rd November 1875, at which Cardinal Manning preached on the Oxford motto Dominus Illuminatio Mea, denouncing the university for its spiritual apathy and decay. Hunter-Blair kept on at Wilde, often sitting up all night talking to him about his religious views. During one heated discussion he hit him on the head and shouted ‘You will be damned, you will be damned, for you see the light and do not follow it.’ Their mutual friend William Walsford Ward, known as ‘Bouncer’ after a comic novel, was present during this debate; he had always opposed Wilde’s flirting with Roman Catholicism and persistently argued for the reasonableness of Protestantism. When he asked Hunter Blair’s opinion about his own salvation, he was met with the reply ‘You will be saved by your invincible ignorance.’

The trio appears in a photograph taken the following year by Hungarian emigré photographer Jules Guggenheim (1820-89). The picture shows a group of students and friends gathered in Magdalen Cloister on the evening of 21st June: Hunter-Blair, Wilde and Reginald Harding are alongside William Ward and his younger sister Florence. Ward left Oxford that summer to become a lawyer and Wilde moved into his old rooms in December.

The following year saw the religious discussion continue without any further development. Hunter-Blair was joined in many of these conversations by another convert, Archie Dunlop, and in the spring they succeeded in bringing Wilde to Rome. Hunter-Blair and Ward travelled to Italy in March and made arrangements for Wilde to follow them, although Hunter-Blair had to send £60 after a series of delays and difficulties arose. Travelling through France and Genoa – where the Holy Week services inspired more poetry – Wilde caught up with his friends at the Hotel d’Inghilterra in Rome. Here they were joined for supper each evening by two papal chamberlains, J. Ogilvie Fairlie and Hartwell de la Garde Grissell (1839-1907). The latter was a close friend of Hunter-Blair who had come up to Oxford from Harrow in 1859, studied at Brasenose and became a Catholic in 1868. When Hunter-Blair made his first return visit to Oxford since graduation in the summer of 1890 he stayed at Grissell’s house in Long Wall Street, overlooking the deer-park and aged elm trees of Magdalen. There was even a private chapel where Hunter-Blair – by then a priest – was able to say Mass. Fairlie was another Oxford friend, a graduate of Christ Church, and had acted as Hunter-Blair’s godfather when he was received into the Church. A papal audience for Wilde was secured through Hunter-Blair’s acquaintance with Mgr Edmund Stonor, Rector of the English College. Hopes for Wilde’s conversion to Catholicism were high and he could be forgiven for frustration and disappointment at his friend’s prevarications. Two incidents – small in themselves – revealed a sharp divergence in opinion between the two students. After the audience with Pope Pius IX they visited the English Cemetery where Wilde prostrated himself on Keats’ grave – an act of devotion which displeased Hunter-Blair. The following June Wilde again incurred his friend’s displeasure with his long poem Ravenna which brought Magdalen its first award of the Newdigate Prize since 1825: Hunter-Blair objected to the description of Vittorio Emmanuel II’s triumphant entry into Rome in 1870. Wilde’s fickleness was evident. After the audience he wrote the sonnet ‘Urbs Sacra Aeterna’ which Hunter-Blair sent to Fr Henry Coleridge SJ, editor of the Jesuit journal The Month; it was published in September but Wilde seemed merely to be playing with moods and Hunter-Blair’s patience had worn thin.

‘I don’t want to see them [sonnets]. It is useless to talk of your weakness and want of principle – truly a strange reason for turning your back on what alone will make you strong…and as for your want of faith and enthusiasm, you cannot pretend to believe that the God, who has given you grace to see His truth, will not also keep you firm when you choose to embrace it.’ Almost ten years later Wilde called on Hunter-Blair in Edinburgh; the meeting was brief and lacked the warmth of their student days. Wilde finally fell on his knees and said ‘Pray for me, Dunskie, pray for me.’ As Hunter-Blair walked out Wilde knelt on the floor and kissed his hand, and that was the last they saw of one another.

Hunter-Blair obtained his MA in 1876 and in the same year was appointed Captain in the Prince Regent’s Royal Ayrshire Militia. His convert’s zeal was not restricted to trying to draw Wilde into the Catholic Church and over the next two years Hunter-Blair poured a fair amount of his wealth into the Diocese of Galloway and other Catholic causes. A number of new churches were built with his financial support. Donations were made to the churches at Girvan, Stranraer – to which he would cycle from Dunskey for Sunday Mass – and it was he who paid for the new church at Newton Stewart, opened on the 7th December 1876 and dedicated St Ninian. His connections with the area remained, and when the church at Stranraer was refurbished in the early 1920s he returned to preach at the grand re-opening. Between 1877 and 1879 he donated a total of £72,677 to Fort Augustus and was largely responsible for the fine monastic library. On the 9th May 1877, along with Robert Monteith (whose relative Anne Monteith paid for a window at Newton Stewart) and his old friends J Ogilvie Fairlie and Rev Archibald Douglas, he was in Rome to present Pius IX with £2,000, a chalice and vestments, as a consolation for the loss of the papal states. A good many ladies had their eyes upon this wealthy young bachelor heir, and in the elegant whirl of high society a series of débutantes were introduced to him in the hope that a brilliant match would be made. To the disappointment of many mothers, if not to him, his vocation lay elsewhere.

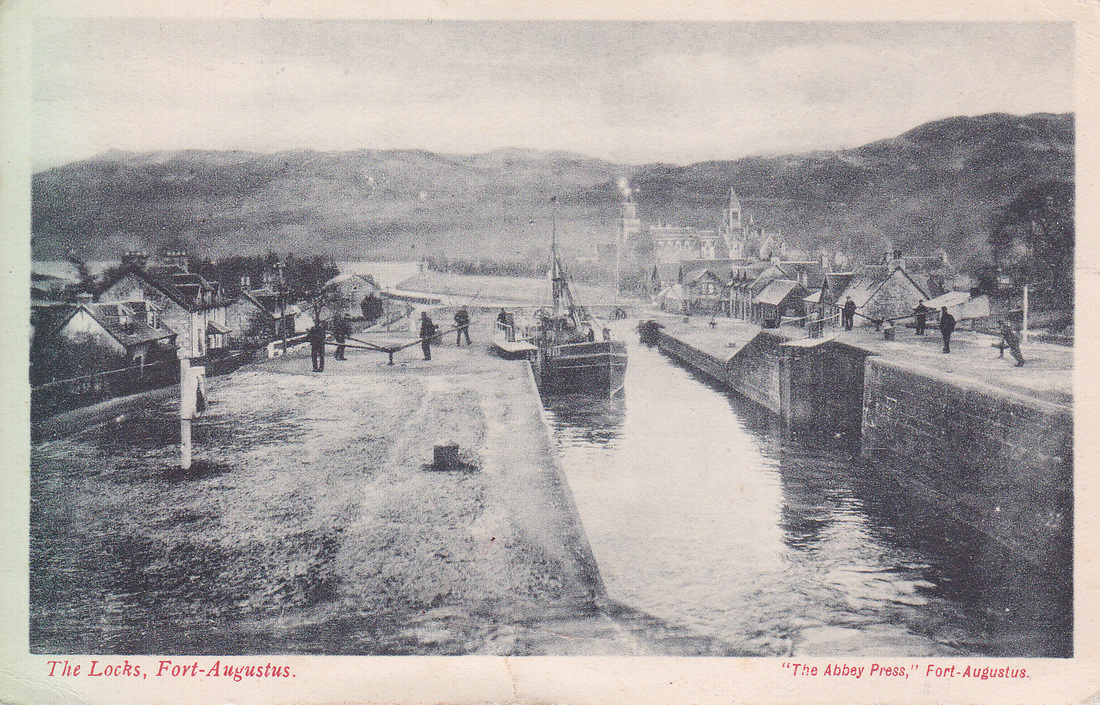

St Benedict’s Abbey, Fort Augustus

The monastery at Fort Augustus was housed in a former military garrison at the south end of Loch Ness and had been given to the Benedictines by the Catholic landowner Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat. The foundation came about through the vision and enthusiasm of Dom Jerome Vaughan OSB in 1876 but was still finding its feet when Hunter-Blair first visited in February 1878. He was evidently impressed and returned in September for the inauguration of the boys’ school. The foundation stone of the monastery was laid by Lord Lovat on 15th September, that of the school by the Marquis of Ripon, and that of the guest-house jointly by Mr Maxwell-Scott of Abbotsford and Robert Monteith of Carstairs. After this, Prior Jerome Vaughan took the 25-year-old on a tour of English monasteries and cathedrals. Returning to Scotland to settle his affairs, he entered Fort Augustus at the end of October and began his postulancy on 11th November, donning for the first time the black tunic and belt of the postulant. When he was clothed as a novice he took the religious name of Oswald. By then the building work had advanced enough to justify a solemn opening ceremony on the 16th October, but the community remained small: in August 1879 there were still only six other monks besides the Prior. In those days the English Benedictines had a common novitiate at Belmont Priory in Herefordshire and he duly set off south at the end of the month. He made his simple profession on 3rd July 1880 and travelled up to Fort Augustus for its long-awaited solemn opening in August, planned to coincide with celebrations for the 1400th anniversary of the birth of St Benedict in 480.

Behind the jubilation, however, tensions were rising within the community with regard to monastic observance. The English Benedictine Congregation (EBC) has a unique history and character: although claiming continuity with the pre-Reformation monks of England, its traditions and structures grew out of the 16th and 17th century experience of monk-missionaries trained on the continent to minister to Catholics in England. This strong pastoral emphasis meant that EBC houses undertook to run parishes and schools outside their monasteries, and individual monks lived far more ‘in the world’ than their counterparts in other Benedictine congregations. Many remained outside their monasteries for years on end, returning only for the annual retreat. Even if few were baronets like Hunter-Blair, most came from privileged backgrounds, something reflected in the general ambience, culture and standard of living within the houses. One of the objections made in 1880 was that claret should no longer be served in the refectory, and more abstinence was demanded two years later, along with greater silence and the exclusion of schoolboys from the monastic cloister. In part, this reflected the influence of monastic reform movements then gathering momentum on the continent; it was also a manifestation of national tensions. The Third Marquess of Bute was pushing for the establishment of a Scottish Benedictine Congregation, and on the 30th September 1882 Lord Lovat wrote to the Archbishop of St Andrew’s and Edinburgh that his land had been intended for ‘an entirely Scotch foundation’. There was also the problem that the Prior, Dom Jerome Vaughan, was not popular within the community.

Matters came to a head and a Papal Brief, formally separating Fort Augustus from the EBC, was read out at Mass on the Feast of the Epiphany, 7th January 1883, by John Strain, Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh. Members of the community currently elsewhere left their EBC houses and returned to the Fort. Vaughan invited Dom Leo Linse, Prior of St Thomas’ Abbey in Erdington, to give the annual retreat to the monks at Fort Augustus, and at the end of the retreat a unanimous petition was sent to the Holy See by all the professed monks asking that he be appointed their Superior. Dom Jerome was deposed by the EBC and left shortly afterwards, to be replaced as Prior by Fr Kentigern Milne. Although the community’s request was not granted at this time, Linse was installed as Prior on 4th April 1886 and finally blessed as the first Abbot of Fort Augustus on 15th July 1888.

Meanwhile Dom Oswald was ordained deacon on March 25th, the same day that his Rule of St Benedict was published. This edition was printed at Fort Augustus by the Abbey Press and contained the Latin text of the Rule accompanied by Fr Oswald’s English translation and notes. It proved popular: a second edition came out in 1906, reprinted the following year, with a third edition in 1914. His ordination to the priesthood took place a few months later, on the 11th July; he was ordained with Dom Adrian Weld-Blundell, a brother of Lady Lovat. It is intriguing to note that the name of another celebrated Magdalen graduate, Lord Alfred Bruce Douglas (1870-1945), was entered in the Abbey Visitor’s Book just a few weeks earlier. By this time Fr Oswald was engaged in translating Geschichte der Katholiken Kirche in Schottland (2vols, 1883) by Alfons Bellesheim, Canon of Cologne Cathedral. The result was a History of the Catholic Church of Scotland, from the introduction of Christianity to the present day published by William Blackwood & Sons in four volumes between 1887 and 1890. It is much more than a straight translation. Fr Oswald added copious notes, expanding and explaining Bellesheim’s text. Few of these are mere glosses; many are highly instructive and extremely useful to historians. He showed himself a gifted translator, turning Bellesheim’s German into easy-flowing harmonious English prose. The book was well-received by critics and remains the most outstanding scholarly achievement of all his literary work. It was an important step in establishing the abbey’s reputation for intellectual and spiritual vitality. Over the next decades this was consolidated by other publications and works of art produced by the community.

During that summer of 1886 he came into contact with the enigmatic Baron Corvo, about whom I have written in A Carnal Medium. Hunter-Blair’s old friend Lord Bute was then engaged in setting up a cathedral choir on the west Highland coast at Oban, but finding it as difficult to locate suitable boy choristers as it was to employ a reliable choirmaster. Four youngsters were eventually chosen and sent to the abbey school at Fort Augustus to learn the rudiments of Gregorian plainchant from the monks. For a choirmaster Lord Bute obtained the services of Frederick Rolfe, ‘Baron Corvo’, who had just been dismissed from the Scots College in Rome – a fact unknown to His Lordship. Rolfe called at Fort Augustus to collect the boys on his way to Oban and met Fr Oswald, who subsequently came to stay in Oban on 13th September. The three months had not been happy ones and Rolfe poured out a litany of bitterness and complaints about his treatment from other Catholics and locals. He abandoned the post in October and left for Aberdeen where he set up as a photographer. Between then and 1898 Rolfe moved through a number of jobs and as many friends. That autumn the Daily Free Press published a series of three anonymous articles on Rolfe – 8th, 12th and 26th November – containing both intimate accurate details as well as stinging accusations. Who was the author? Hunter-Blair was one of those suspected, but it is doubtful if this will ever be confirmed. Another shady character who visited the abbey around this time was Ada Goodrich-Freer. She mentioned her intended visit to Fr Oswald in two letters written on 15th August 1894; one to Lord Bute, the other to Frederick Myers who had put her into contact with the monk. He describes this month on page 203 of A Medley of Memories without reference to her.

He was headmaster of the school until 1888 when Abbot Leo appointed him master of scholastics i.e. newly professed monks studying for the priesthood. By the autumn of 1894 several of them were within a few months of ordination, emphasising the problem of providing studies. At one point it seemed that a hall might be opened at St Andrews University: the 3rd Marquess of Bute was then Lord Rector and was eager – for patriotic and romantic reasons – to open a Scottish seminary there. Fr Oswald met Lord Bute several times to discuss the plan, even reaching the stage of opening negotiations with the Dean of Faculty there, but it came to nothing. In the autumn of 1896 he returned to Oxford again as guest of Hartwell Grisell and found the university community full of interest over the new hall for Jesuit students about to be opened with Fr Richard Clarke SJ as its Master. An 1882 statute allowed any individual with an Oxford MA to open a Private Hall in his own name, and the Jesuit house of studies was opened as Clarke Hall. This development would turn out to be of direct relevance to Fr Oswald’s future career, but for the time being his eyes turned elsewhere, for in (April) 1896 he embarked on a steamer for South America.

The Beuronese congregation, to which Fort Augustus was affiliated from 1883 to 1911, had accepted a request for help from moribund Benedictine communities in Brazil by sending out a small party of monks in April 18957. Fr Oswald had been asked to assist in the restoration by Dom Gerard van Caloen who had been Rector of the school at Maredsous when he visited the Belgian monastery in 1883. Brazil had been a Belgian colony until the collapse of the Empire in 1889, by which time the entire Brazilian Congregation comprised barely a dozen monks. Fr Oswald was sent to the oldest Benedictine monastery in the country, St Benedict’s, Olinda. The Anglican chaplain here, curiously enough, had been a chorister at Magdalen while Hunter-Blair was an undergraduate. He married in 1895 and returned to Scotland for a three-month honeymoon on Loch Tay. His chapel at Pernambuco was a barn-like structure of corrugated iron. Macray died of yellow fever soon after Fr Oswald returned to England in time for Easter 1897.

That summer saw the purchase by his old friend Lord Bute of Pluscarden Priory, a partially-ruined monastery near Elgin. The Marquess acquired the property for his youngest son but hoped that the buildings could be restored and possibly returned to their original purpose. He invited Fr Oswald to celebrate Mass in the prior’s chapel at Pluscarden, and this took place on 5th May 1898. The scene was later painted by an artist, Horatio Walter Lonsdale, with whom Lord Bute was then working closely.

Return to Oxford Later in the year Fr Oswald returned to his old college to attend the Magdalen ‘gaudy’. In June he was back at Fort Augustus after an absence of almost eighteen months, but his sojourn there was to last barely a year, for in at the end of August he left the Highlands to return to Oxford.

The Benedictine hall in Oxford owed its origin to the Prior of Ampleforth, Fr Anselm Burge. The decision was made at a meeting of the Prior’s Council on 22nd July 1897 and twenty-six-year old Fr Edmund Matthews OSB was appointed superior. Along with three young postulants Fr Edmund arrived in Oxford early in October 1897, moving into premises at 103 Woodstock Road opposite St Philip and James Church. The foundation foundered however in that Fr Edmund was not a Master of Arts, and this degree was required by the university for anyone wishing to maintain a private lodging hall of undergraduates. As no-one at Ampleforth had an MA the future of the hall looked uncertain until Fr Oswald offered his services. He was not just a Master of Arts but also a graduate of Oxford; furthermore, his social skills provided a means of gaining acceptance for the monks within the Oxford community. To satisfy the university rules he had to reside for a short period before he could be granted a license, and he moved in accordingly on 1st September 1898. License to open a Private Hall was obtained on the 29th May and Hunter-Blair Hall opened in October 1899 with himself as Master; Fr Edmund took care of general management until his recall to Ampleforth in 1903. In these early years the hall received much help from Hartwell Grissell.

Frederick Rolfe contacted him in 1901, hoping to enlist his help in finding a publisher for Chronicles of the House of Borgia. For some reason Rolfe turned on Hunter-Blair and directed a furious onslaught of invective against him. In 1904 Hunter-Blair moved the Benedictine house to new premises in Beaumont Street in the former Grindle’s Hall. Students included Justin McCann, who was the first monk from the Hall to obtain a First. Fr Oswald became a well-known and popular figure around Oxford, but by 1908 his health was causing concern and it was revealed that he would need a major operation. This effectively ended his term as Master. He returned to Oxford to spend a year as assistant Catholic chaplain and then embarked for Brazil to help at the monastery of San Bento in Sao Paolo.

Back at Fort Augustus Abbot Leo’s health had also deteriorated, so much so that he returned to Germany to be treated for diabetes: he did not return until the autumn of 1909. In his absence Prior Kentigern Milne had been in charge of the monastery, but the Abbot’s condition was so poor that it was evident he could not resume responsibility. He moved to the monastery’s “holiday home” St James’, at Letterfourie near Buckie, where he died on the Feast of St Benedict, 21st March 1910. The monastery ceased to be an independent abbey affiliated to the Beuronese Congregation and instead rejoined the EBC. Prior Hilary Wilson of Ampleforth was appointed claustral Prior during the inter-regnum which ended with the election of Fr Oswald as the second Abbot of Fort Augustus.

He announced his determination to complete the abbey church, which still lacked a choir, and made this one of the priorities as abbot. The community then numbered about forty with some of the monks serving parishes outside the monastery. The school had been closed in Christmas 1894 as part of the Beuronese reform, continuing in a much-reduced scale as a junior seminary for around twenty boys considering a vocation to the priesthood or monastic life. He had been abbot for just over a year when the First World War erupted. Although it was not yet apparent, the society that he had known had ceased to exist. The college buildings were handed over for use as a military hospital and occupied by wounded Belgian soldiers. Several monks left to serve as chaplains in the army or navy; some, like Frs Odo Blundell and John Lane-Fox, distinguished themselves. It was a challenging time to be abbot. Many local families lost fathers, husbands and sons in the war. Resources were scant and his own health poor. The horrors of modern warfare ended the confident carefree Edwardian era, confronting mankind with proof of its own inhumanity. The introduction of airplanes and tanks was frightening enough, but submarine warfare was the most sinister development in the eyes of many – including Pope Benedict XV who considered their attacks on shipping as beyond even the laws of war. In 1911 Abbot Oswald had noted the arrival of two naval submarines – ‘weird, wicked-looking brown things’ – in Loch Ness. The modern world was breaking in. After the war even the grandest celebrations were more sober. The vast social balls at country mansions that he had known in his youth, with processions of carriages and footmen in livery, were not to be repeated. His memoirs contain much that seems redolent of the 18th and early 19th century, belonging to an era that ended with the coming of the railway rather than the submarines.

He resigned as abbot in November 1917 just after the solemn blessing of the Blessed Sacrament chapel by Bishop Aeneas Chisholm of Aberdeen. The choir had just been finished, although the entire church was not to be complete for another half-century. The retired Abbot followed the usual practice of moving away from his abbey for a while in order to give breathing space to his successor. As it happened there was another two-year interregnum during which Fr Hilary Wilson was again claustral prior. The EBC have a tradition of granting retired abbots the titular abbacy of an old pre-Reformation monastery and Abbot Oswald became – for the time being – titular Abbot of Abingdon. The suggestion of spending his retirement at the Benedictine House of Studies in Oxford was quashed by his former pupil Dom Justin McCann, appointed Master in 1920. He therefore moved at the age of 66 to Caldey Island off the coast of South Wales, the home of a Benedictine community of former Anglicans who had joined the Catholic Church in 1913. Their journal PAX carried his Rome Forty Years Ago: some rambling recollections in their autumn 1917 issue, with the second part of the article appearing in the winter number.

The community was in fact struggling with financial and personal difficulties, and the Superior – Dom Aelred Carlyle – left in December for a fund-raising tour in America. As he had still not returned by Easter 1918 Abbot Oswald officiated at the Holy Week services and preached on Easter Sunday. His presence was a welcome one. His gifts as a raconteur were appreciated by most (but not all!) of the community, which he also served as acting librarian. Much of the time was spent on literary work, a biography of Lord Bute as well as his forthcoming memoirs. Chapters from the latter were read to Br Richard Anson who provided the illustrations. Extracts were published in PAX. Abbot Oswald remained on Caldey Island for two and a half years, albeit with occasional journeys for important functions. He returned to the Highlands for the blessing of his successor, Abbot Joseph McDonald on 27th August 1919. While at Harrogate on the way home he heard that his titular abbacy was to be moved from Abingdon to Dunfermline – the only old Scottish abbey associated with the English Benedictines.

A Medley of Memories, the first of three entertaining volumes of memoirs, was published in 1919. (The other two came out in 1922 and 1936). Amongst all the thousands of books and articles written by Benedictine monks over the last 1,500 years there is nothing quite like Hunter-Blair’s trilogy. His gifts as a raconteur were obvious, but the never-ending litany of country houses, famous names and exotic locations presented an extraordinary picture of monastic life. Publication coincided with Abbot Cuthbert Butler’s Christian Monachism, an erudite, convincing and influential work that quickly became a classic. Comparing the two, one critic commented that Butler wrote about monastic life as it should be, while Hunter-Blair’s book showed it as it is. His trilogy of Medleys says little about mysticism but a great deal about high society. The abbot’s human failings may have included excessive concern with worldly affairs, yet this should neither obscure his achievements as a monk nor be presumed to imply lack of religious devotion or disregard for prayer. Most of a monk’s life is hidden, known only to God. While some monks may have worn silk-lined hair shirts Abbot Oswald could not be accused of hypocrisy, for he was extremely candid about his extra-mural activities; so much so, in fact, that it appears almost as a smokescreen. He was an intelligent man. Few abbots are fools.

He left Caldey on March 23rd 1920, having accepted another invitation to assist in Brazil. On his way to Southampton he stopped over at Bristol with Dr Tetley, the Archdeacon of Bristol and an old Magdalen man whose daughter had become a Catholic. At a Magdalen gaudy Hunter-Blair had met a previous Archdeacon of Bristol (and chaplain to Bishop Samuel Wilberforce) Alfred Pott. From Southampton he sailed for Brazil, arriving back at San Bento on April 19th 1920. He left in August and by the autumn was back in Fort Augustus where he completed the final pages of Life of the Third Marquess of Bute. Early in 1921 he sailed back to Brazil and reached San Bento on February 10th 1921. He left in November and reached England mid-December. The Beuronese encouraged artistic work and the abbey had its own Arts & Crafts school which made a rosewood screen for the Blessed Sacrament chapel at Fort Augustus.

|

From then on he was never able to settle. He travelled about, acting as chaplain to noble families, writing prolifically for books and magazines, and residing for some years at the New Club in Edinburgh’s Princes Street. He was constantly in demand as a speaker for church events, jubilees, weddings, radio broadcasts, dinners, and social functions, at which he was always the life and soul of the gathering. Hunter-Blair took part in the abbatial blessing of Dom Edmund Matthews, his former Oxford colleague, on 12th March 1925. In 1927 he was on the BBC broadcasting on the subject of ‘Scottish Monasticism’ before leaving for Brazil again in the winter months. On December 8th 1928 he kept his Golden Jubilee, marking fifty years since he began his novitiate. |

In noting the occasion the Benedictine Almanac and Guide for 1930 acknowledged that ‘English Benedictines are especially indebted to him as the first Master of the Benedictine Oxford House of Studies, for whose help in an acute emergency, and in many years of service, we can never be sufficiently grateful.’ (p.15. Photograph above.)

On 7th January 1935 he took part in the inaugural meeting of the Fort Augustus Old Boys’ Association at the Caledonian Hotel in Edinburgh, presiding over their London dinner at the Rembrandt Hotel in London the following month. He told the gathering that he was shortly travelling to Rome to see Pope Pius XI and would ask the Pope for a special blessing for them all, at which point the audience burst into singing ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow.’ A few weeks later he was back in Oxford, for the Scottish Catholic Observer reported on 9th March 1935: ‘The Lord Abbot of Dunfermline, Abbot Hunter Blair, gave a lecture last week in the Society’s rooms at the Old Palace (now the residence of Fr Ronald Knox) on the famous Monster of Loch Ness. Many distinguished members of the University attended.’ He was off to Rome next where he stayed with the Abbot Primate on the Aventine and had a private audience with Pius XI on March 27th. The two men seemed to have got on well together. Eschewing the formality of his predecessors, the Pope asked Abbot Oswald to sit next to him. The monk showed him a picture of the monastery’s setting by Loch Ness and Pius XI cried out in delight ‘Enfin, nous l’avons – l’habitat du Monstre! It turned out that the Pope had long been fascinated by the Loch Ness monster and had been unsuccessfully quizzing Scottish bishops and priests for details. Once Hunter-Blair admitted that he had in fact seen the creature, it proved impossible to steer the conversation onto any other subject.

By his early eighties his health – never strong – had begun to deteriorate and he suffered much from rheumatism, gout and failing sight. Despite this he remained active, with neither his brain nor his pen lying idle for long. Even if his “unwillingness to let the monastic life interfere with his social engagements”11 had led him to spend most of his time outwith the cloister, his heart remained in the monastery where he made profession. Lying ill in St Mary’s Hospital, London, he knew that death was drawing near and asked to return to St Benedict’s Abbey. He was taken on train back to Fort Augustus where he died on September 12th 1939, and buried in the abbey cemetery.

To monks today he cuts a rather comical figure, seeming to belong more to the pages of a novel by Trollope or Dickens than to the Vitae Patrum. Since the beginnings of Christianity monks have made their dwelling in deserts, mountain caves, on remote islands and even atop pillars, none of which seems as incongruous as Edinburgh’s New Club – but this image he himself presented, and it is easy to be fooled by the impression. His aristocratic connections and evident enjoyment of them may seem out of keeping with the renunciation of his monastic vows, but these were deliberately employed for higher ends. In an era when the establishment tended to identify Catholicism with Irish navvies and foreign Jesuits, the charms of this literary baronet were a revelation. The fact that he was a monk – and a highly capable one – added to his effectiveness in making Catholic religious life acceptable. There were still violent attacks being made on the presence of a Roman Catholic monastery in Scotland in newspapers in 1888. The ease with which he glided through the upper classes enabled him to advance Catholic causes that might otherwise have been obstructed: his success in gaining a foothold for the Benedictines in Oxford is just one instance. Abbot Oswald may sometimes have acted the clown, but his mind was more shrewd than he let on. Despite the huge amount this colourful and flamboyant figure wrote about himself, one suspects that it was always less than the full story. This monk of Magdalen continues to fascinate, to entertain and to confound; in being a sign of contradiction, even to himself, he stands firmly in the monastic tradition.