On Sunday 23 October 1938 an ‘eighteen-year-old girl’ named Maude Courtney announced to the press that she and Walbrook – whom she had known for three months – were engaged to be married. She then withdrew the statement, issuing a denial of their engagement, before announcing it again a few hours later. It was stated that official notice of their intention to marry had been submitted to St Pancras Registry Office, but within 48 hours the engagement was called off again, this time for good. What on earth was going on? And why did Maude’s mother take such a prominent role in the story? As both mother and daughter belonged to Charles B Cochran’s famous company of ‘Young Ladies’, some background may help.

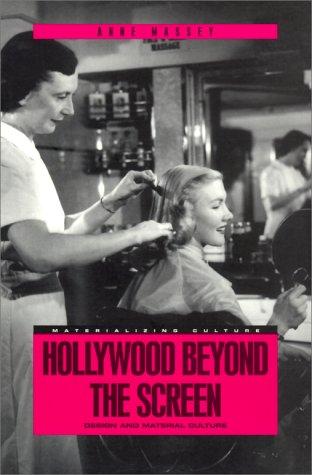

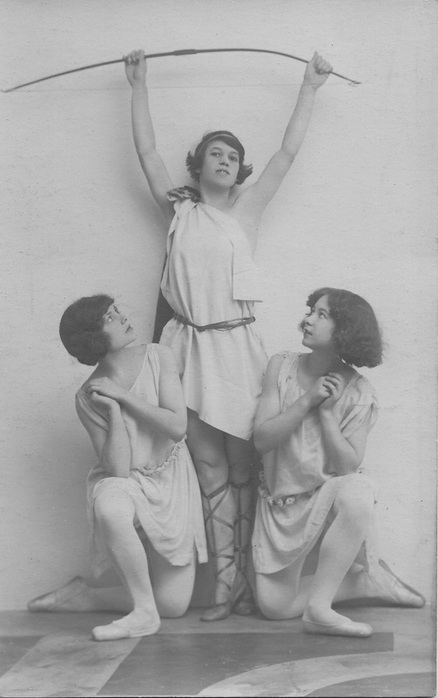

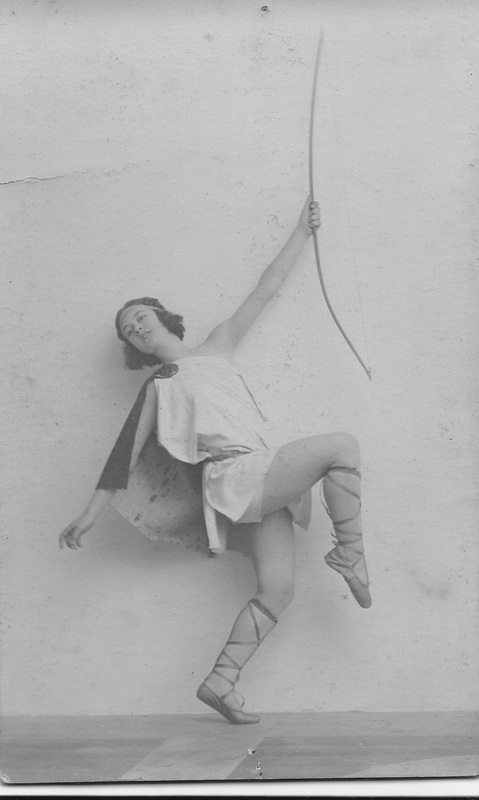

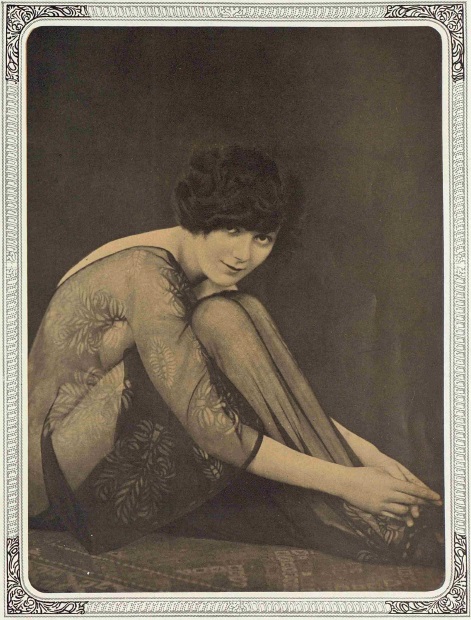

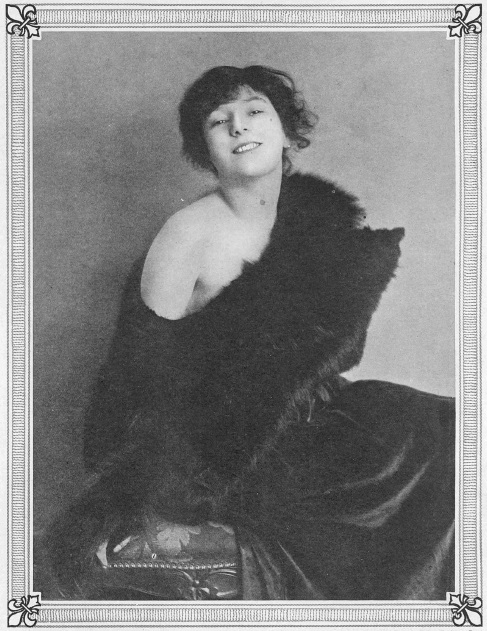

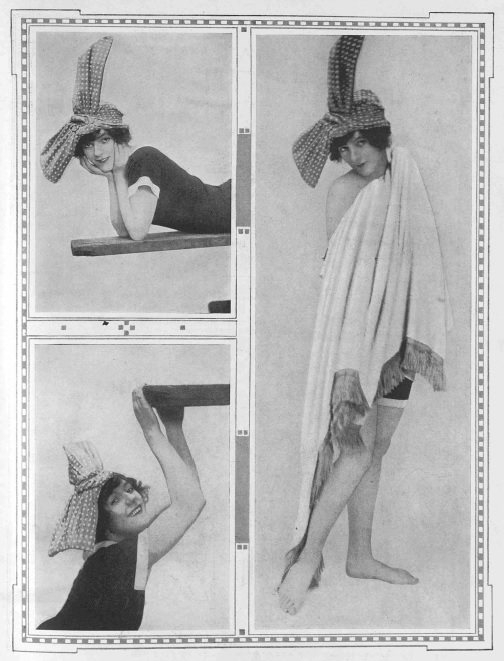

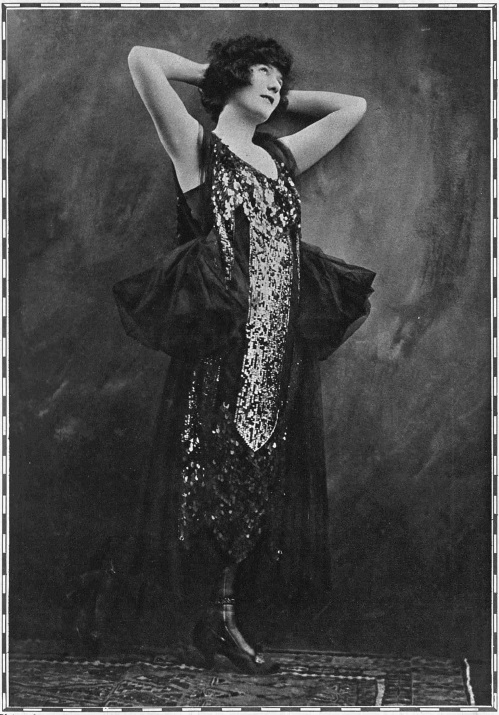

Fannie Barbara Birdie Coplans was born in Canterbury in 1891, the daughter of Russian emigres from Poland named Koplanski. No occupation was given in the 1911 census and she seems to have made her debut under the stage name of Birdie Courtney in Charles B. Cochran’s revue More at the Ambassadors Theatre in June 1915, from which the photograph at the top was taken. She caught the eye of both critics and audiences, and was soon featuring prominently in the press, as well as having her portrait taken by notable society photographers such as E.O. Hoppé

Having been singled out from a large line-up of chorus girls for attention, it was natural that Birdie would be offered a more prominent role, and she moved from the Ambassador to the Comedy Theatre to play a number of colourful parts in Half Past Eight.

Evidently the press were interested in Birdie in more ways than one, for on 22 July 1916 she married Mr Randal Charlton, a novelist member of the Daily Mirror‘s editorial staff, at the church of Our Lady and St Edward, Chiswick. His best man was Horatio Bottomley MP and it was quite a society wedding, with MPs and show-business personalities among the guests. Charlton (whose real name was Lister) was the author of novels such as Mave (1906) and The Virgin Widow (1908) and had been a devoted fan of music hall star Marie Lloyd. Their daughter Maude was born eight months later, on 24 March 1917. Two sons followed, Warwick in 1918 and Frederick in 1928. The latter was only three years old when Randal Charlton died in 1931, by which time Birdie had established a reputation as a writer of short stories.

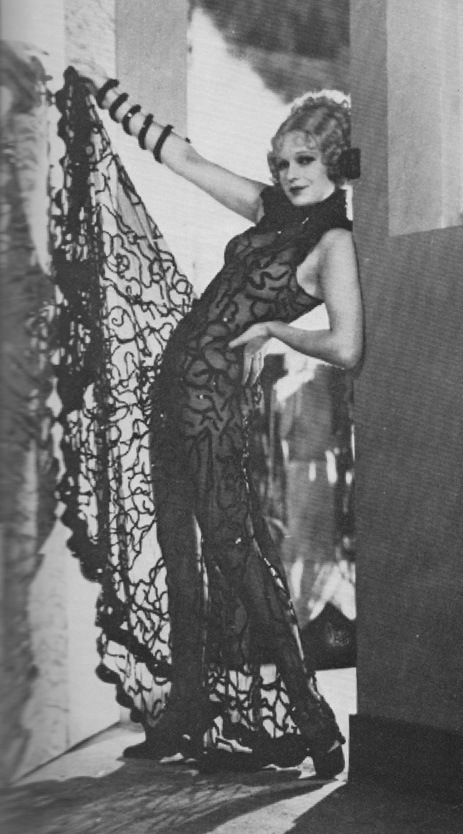

At some point Maude followed her mother onto the stage: although newspapers described her as a ‘London dancer’ and ‘one of Charles B. Cochran’s “Young Ladies”’, she seems to have worked under a stage name, doubtless to avoid confusion with the well-known American vaudeville performer Maude Courtney (1884-1959), who was a regular feature in London music halls during this period, often appearing alongside her husband ‘Mr. C’ – Finlay Currie, who later co-starred with AW in 49th Parallel and Saint Joan. It is therefore not easy to trace details of any of her stage appearance, or work out where she might have met AW. He was, however, just about to launch his theatrical career in Britain with Design for Living and had been meeting with actors, producers, theatre managers and performers since his arrival in the UK the previous January. Although Cochran’s association with dancing girls and variety shows might be taken as implying a certain frivolity, he was a brilliant showman and took his work seriously. He had gone to see Max Reinhardt’s Oedipus Rex at the Circus Schumann in Berlin, and – impressed by his imaginative use of the vast space – persuaded Reinhardt to collaborate in a staging of The Miracle in London in 1912, at which the huge Olympia hall was transformed into a medieval cathedral. Cochran had a shrewd eye for picking out stars, and worked with the likes of Evelyn Laye, Jessie Matthews, Diana Manners, Gertrude Lawrence, Noel Coward and Leonard Massine during the interwar period, as well as collaborating with Diaghilev and Oliver Messel while producing the Ballet Russes. Making no distinction between high culture and popular entertainment, Cochran staged everything from Faust to Houdini, wild west rodeos to Eugene O’Neill.

Anna Neagle, with whom AW had co-starred in Victoria the Great (1937) and Sixty Glorious Years (1938), started her theatrical career as one of Cochran’s chorus girls. Known then as Marjorie Robertson, she had worked her way up from being a dancer and understudy for Jessie Matthews to a leading role in Stand Up and Sing (1931). Perhaps AW’s meeting with Cochran’s company came through Neagle?

Reporters seeking a statement from Walbrook about the surprise engagement were to be disappointed, as inquirers who called at his house in Holne Chase were turned away at the door by one of the servants, who told them he was ‘out of town’. Another member of the Courtney family was willing to talk, however, and told reporters that the couple were going into the country until their marriage, later this month, after which a friend was lending them a yacht on which to take a four-week honeymoon. Maude regarded Walbrook as ‘quite the most romantic person in the world and quite the shyest.’

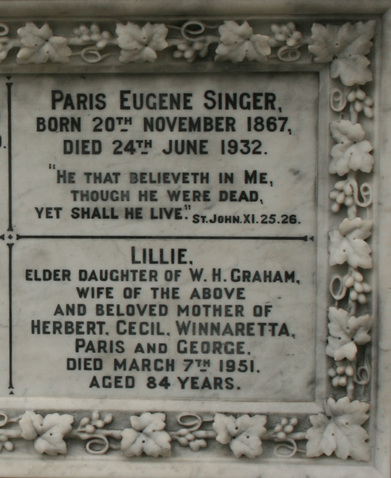

Walbrook: ‘A Man without a Country’

Two days later, the story had taken a dramatic twist, as a large article appeared in the same newspaper headed ‘Film Star’s Wedding Vetoed. Girl’s Mother Objects. Miss Maude Courtney as ‘subject of Hitler.’ Nationality bar. Mr Anton Walbrook ‘a man without a country.’ The story went on to explain that as of yesterday, (Wednesday 26 October) the wedding was officially ‘off’. Legal advice had been taken and a formal statement issued by Messrs Henry Solomon & Co., solicitors, dated Tuesday, following a meeting between Walbrook and Maude’s family. Although aware of their close relationship, Mrs Charlton had been ignorant of their intent to marry, and made her views clear: ‘In the present state of European turmoil, I dare not think of my daughter becoming an alien, being married to a man without a country, and a subject of Herr Hitler. Maudie is of course terribly disappointed – broken-hearted. They are still friends, and if there is anyway of surmounting the barrier, the wedding will take place as soon as ever the difficulties can be straightened out. Mr Walbrook is a refugee – he had a Jewish grandmother – and Maudie is a Catholic. Her family is descended from the Plantagenets and is mentioned in the Domesday Book. It is one of the oldest families in England. How could she sacrifice this heritage to become an outcast?’ Mrs Charlton made it clear that Walbrook’s nationality was her sole objection to his marriage to her daughter, and told reporters ‘Personally, I think he is a very charming man.’

Much of this whole affair makes little sense, and carries with it more than a hint of a publicity stunt. Many of Birdie Courtney’s statements about Maude’s age and ancestry do not tally with public records: Maude’s birth certificate makes clear that she was already twenty one – not eighteen – at the time of the engagement, rendering the entire legal issue about consent a nonsense. Were the solicitors really unaware of her real age? However, given Walbrook’s longstanding dislike of media attention, the idea of a fake publicity stunt sounds almost as implausible as that of an engagement to a young chorus girl whom he had only just met. Little did he know that within a matter of days he would begin a relationship that – in contrast to the Cochran affair – would last for almost a decade. Maude eventually found a husband in 1948, while her mother remarried in 1941, but neither mother or daughter seem to have made further progress with their theatrical careers. One wonders if they retained an interest in Walbrook: did Maude ever go to see the actor on stage and feel tempted to nudge her neighbour and whisper, ‘We were once engaged to be married?’