Continuing on the Scottish theme, this week’s cdv comes from the Edinburgh studios of James Ross (1815-95) and Thomas Pringle (died 1895), who were in partnership from 1867 until 1883.

Pringle – an assistant in the firm for many years – became Ross’s business partner following the retiral of John Thomson (born 1808/9) – not to be confused with another Edinburgh photographer named John Thomson (1837-1921) who became famous for his views of China and London street life.

James Ross was working with the calotype process when he went into partnership in 1848 with Thomson, a skilled daguerreotypist. They were appointed photographers to Queen Victoria in 1849, and later switched to using glass negatives following the introduction of collodion in the early 1850s.

James Ross has been in the news recently because of the hypothesis – advanced by American researcher Patrick Feaster – that he may have been the first photographer to produce a sequence of moving images, preceding the man usually accorded that honour – Eadweard Muybridge – by two years. Feaster’s theory is based on a reference in The British Journal of Photography, 14 July 1876, which describes a sequence of three photographs taken:

by Mr. Ross, of Edinburgh, in one of which a girl on a swing is caught just at the instant when the rope had reached the highest elevation; in another a girl is skipping, the picture showing the rope passing under her feet; while a third is that of a boy jumping over a large stone. The last is peculiarly interesting, as it was stated to be taken with a camera fitted with a number of medallion lenses, placed in threes, one above another. The exposures were made by causing a sheet of metal with a hole in it to fall so that the aperture was for an instant brought successively in front of each lens. To the lower end of the sheet was attached a heavy weight, and it was held up in such a position that the three lenses were all covered. At the proper moment the suspending thread was severed, and, although the time between the passing of the opening in the sheet from one lens to another must have been almost inappreciable, the plate showed the three pictures in very different positions.

It would appear from this passage that Ross used a single camera, but one that was specially-constructed with three lenses, allowing him to take three photographs of a moving person, animal or object in rapid succession. Muybridge used a line-up of twelve cameras to photograph a running horse in California in June 1878, with each camera activated by a trip wire as the horse passed by. His experiment was carried out to settle debate over whether a galloping horse ever had all four hooves in the air at the same time. He was able to carry out a series of trials using an array of equipment thanks to the financial support of Leland Stanford, a wealthy horse-owner and businessman. James Ross appears to have funded his own, more modest, experiments himself. For a fuller version of Feaster’s theory, see his article here.

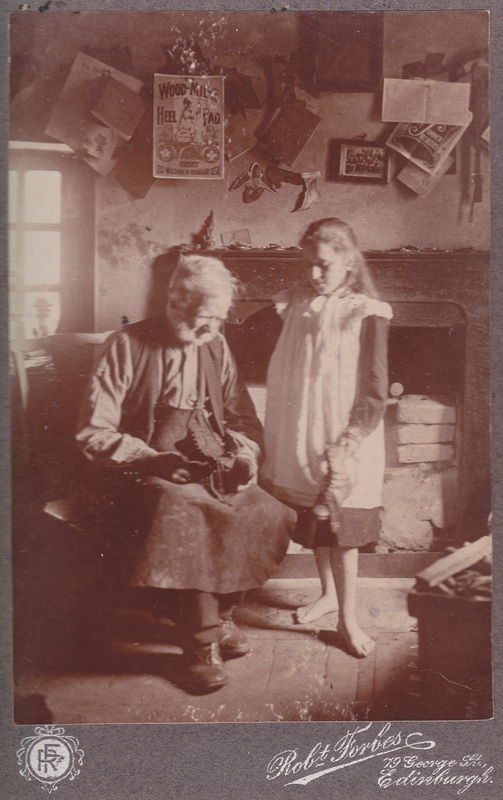

This attractive little family group sat for their portrait around the time that Ross was working on his motion photographs, as a handwritten note on the back gives the date as July 1875 – shortly before Ross and Pringle moved from 114 George Street to 103 Princes Street. The studio was at the west end of George Street, close to Charlotte Square. The mother and her young children may have lived in the west end, but studios with a good reputation such as Ross and Pringle could attract clients from quite a distance. The only clue to their identity lies in the scribbled names and initials at the foot of the card.