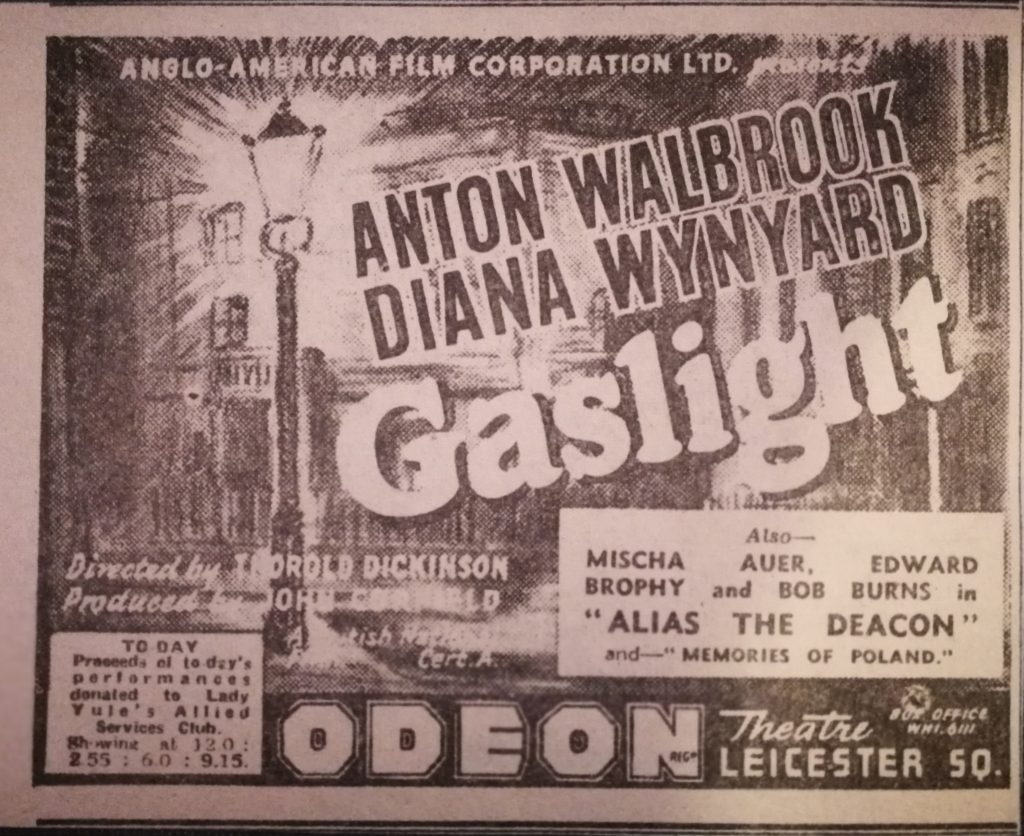

Part of the value of looking at historical artefacts is that they often reveal things about how an artwork or event fitted into its contemporary surroundings. The cutting below was snipped out of a British newspaper in 1940 – the rest of the paper has gone, so I don’t have a precise date, but we know that Gaslight received its general release on 31 August 1940, following the trade and press shows at the end of May and beginning of June.

As many of you will be aware, cinema-going habits in the 1930s and 1940s were very different from ours. Cinema tickets cost only a shilling or two at most, often less, and it was quite common to go to the movies two or three times a week. Films were shown several times a day, but not in isolation as is the case now – they were part of a longer and varied programme which ran almost continuously throughout the day, and would include newsreels, short films, serial episodes, documentary features and cartoons.

It can be seen here that there were four daily screenings – Midday, 2.55, 6.00 and 9.15 pm. Showing alongside Gaslight were two other films – Memories of Poland, which was presumably a short documentary relating to the country’s past prior to the Nazi invasion the previous year, and Alias the Deacon (Cabanne, 1940), a wild west comedy about a card sharp named Deke Caswell who is mistaken for a clergyman. The lead role was played by Bob Burns, a musical comedian famed for playing a home-made instrument which he called his ‘Bazooka’ – a name that was later applied by American soldiers to their anti-tank weapon, due to its similar shape.

For those of us who have only watched old AW films in the comfort of our homes on DVD or video, or at special screenings attended largely by nostalgic fans, film historians and others who may have travelled large distances at some expense to attend these rare events, it is worth thinking about the differences in our cinema-going experience. How would it feel watching Gaslight straight after a cowboy film with a comedian playing his bazooka? Would the contrast make the film seem darker, or would there be a light-hearted atmosphere in the auditorium that might mitigate its sinister psychological undercurrents? What if the audience contained large numbers of casual viewers who had just popped in for something to do, to watch the latest newsreels or catch some cartoons while avoiding the rain? Admission times were not enforced in the same way, and it was not unusual for people to wander in halfway through a film and continue to watch through the entire programme until the first half of the film came round again. There may well have been differences between smaller provincial cinemas and more prestigious venues like the Leicester Square Odeon, to which this advert refers.

Another interesting feature of the advert is he reference to Lady Anne Henrietta Yule (1874-1950), a wealthy widow who became involved in the British film industry following the death of her husband, businessman Sir Andrew Yule. She cofounded the British National film company with Gaslight producer John Corfield and J. Arthur Rank, with whom she shared strong religious views, and went on to invest in the company’s acquisition of Pinewood Studios. She also helped finance The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. Eccentric and patriotic, she was a keen supporter of various charitable and wartime causes, such as the Allied Services Club for which the day’s cinema takings were being collected. How might awareness of this collection have influenced cinemagoers’ attendance?

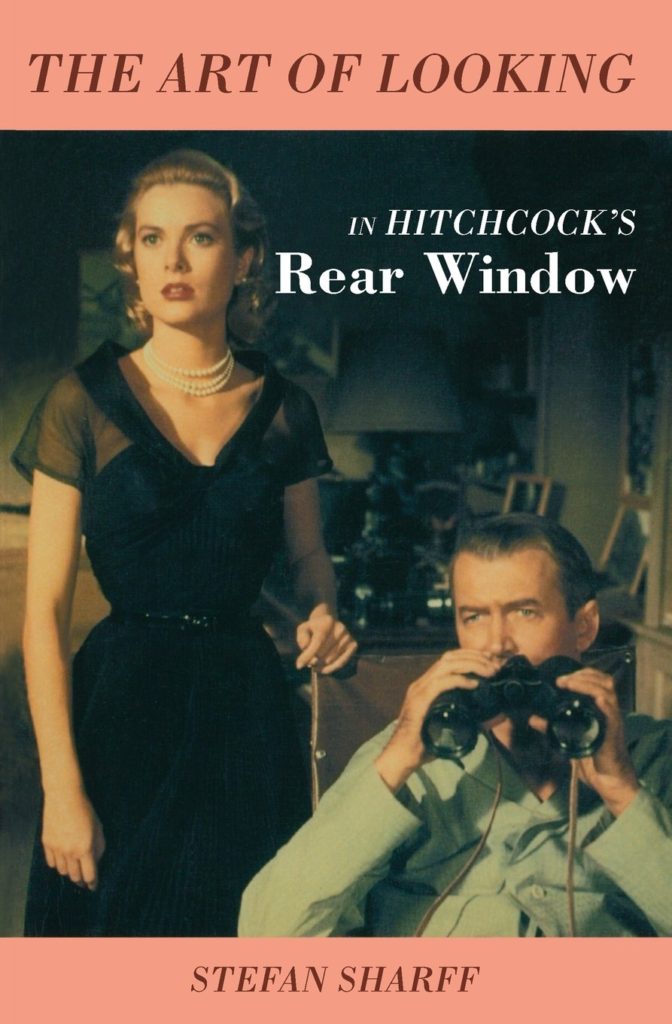

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window

James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a scene from Rear Window