Hansi Knotek (1914-2014)

Starred with AW in Die Zigeunerbaron (1935)

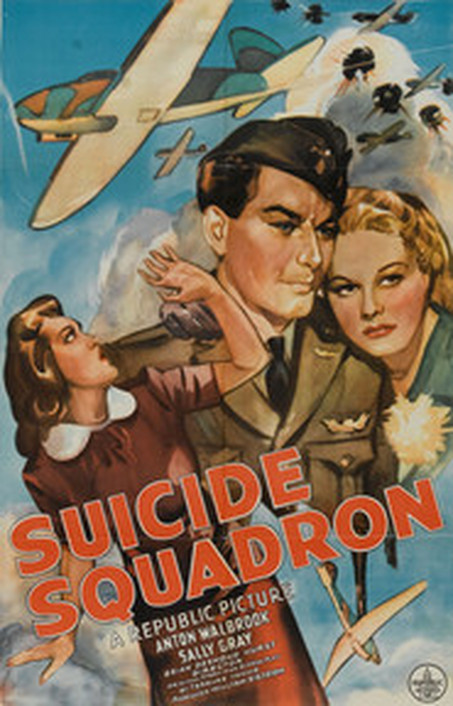

Hansi as Helga Christmann in ‘Das Mädchen vom Moorhof’ (1935), directed by Douglas Sirk and released a few months after ‘Zigeunerbaron.’

It is rather remarkable to think that we lost Hansi only a few months ago: she died on 23 February this year, just days before her 100th birthday. Born Johanna Knoteck in Vienna on 2 March 1914, like Ullrich and Wessely in my last blog post, she studied at the Vienna Academy of Music and the Performing Arts. Her great aunt Katharina Schratt was a well-known actress in Vienna, although her fame was due to her intimate relationship with Emperor Francis Joseph I rather than her stagework.After making her stage debut in Marienbad, Knotek appeared in provincial theatres around Austria before going before the cameras for Schloß Hubertus (1934) in which she played the daughter of a Bavarian count. The film was a typical ‘Heimatfilm’ – a genre of family drama set in homely, rural locations, usually the mountains. Despite her abilities as an actress, Knotek was cast in similar roles throughout her career and thus denied the opportunity to really distinguish herself.

Hansi and AW in ‘Zigeunerbaron’ – her third film

The part of Saffi is typical of these roles – that of a sweet-natured and simple girl, who relies on traditional values to see her through a series of mild tribulations. Based on Strauss’s operetta, Zigeunerbaron is a lively story full of singing gypsies and exuberant dancing, along with the usual comic twists involving disguises and mistaken identities.

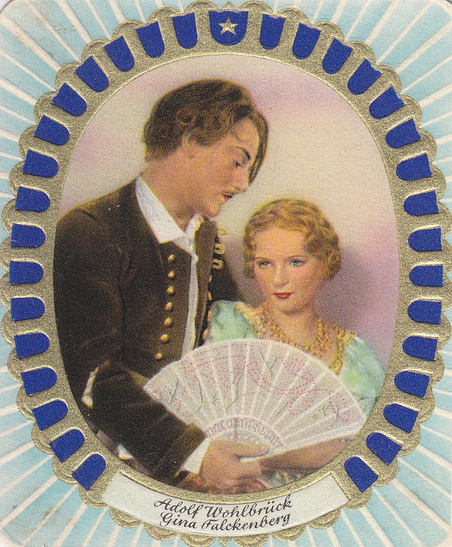

Hansi played gypsy girl Saffi, who falls in love with Sandor Barinkay (AW) after he defends her from arrogant farmer Zsupan, but then becomes worried that Barinkay is more attracted to Zsupan’s beautiful daughter Arsena (Gina Falckenburg – below)

Hansi played gypsy girl Saffi, who falls in love with Sandor Barinkay (AW) after he defends her from arrogant farmer Zsupan, but then becomes worried that Barinkay is more attracted to Zsupan’s beautiful daughter Arsena (Gina Falckenburg – below)

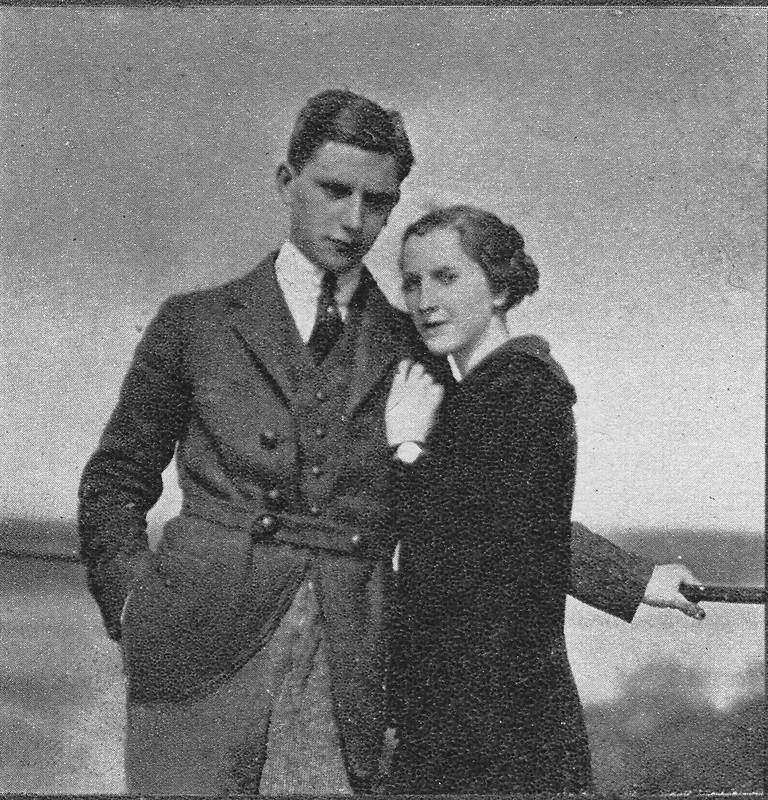

AW and Hansi Knotek on their way to Dalmatia, in the former Yugoslavia, where much of Zigeunerbaron was filmed.

Like AW, Hansi Knoteck continued to work in the theatre while pursuing a screen career. Karl Hartl directed her in other films following Zigeunerbaron, including the popular Der Mann, der Sherlock Holmes war (1937) in which two conmen – played by Hans Albers and Heinz Rühmann – impersonate Holmes and Watson, leading them into a real-life crime mystery as well as romance with two English sisters, Jane (Knoteck) and Mary Berry (Marieluise Claudius.)

In 1940 she married Victor Staal, with whom she had co-starred in eight films, and they remained together until his death in 1982. She made several films during the 1950s before her final screen appearance in Der Jäger von Fall (1974) – like her first film, Schloß Hubertus, and no less than five of her other ‘Heimat’ movies, this was adapted from a novel by Ludwig Ganghofer, Given her long association with these ‘mountain and home’ films – with titles such as Winter in the Woods, Forest Fever, Silence of the Forest, The Laughing Mountain and In the Shadow of the Mountains – it was fitting that she spent her final years in a retirement home in Eggstätt, a thickly-forested area of lakes at the foot of the Chiemgau Alps on the border between Bavaria and Austria. It was here that she died seven months ago. Hansi is buried in the Nordfriedhof (North Cemetery) in Munich.

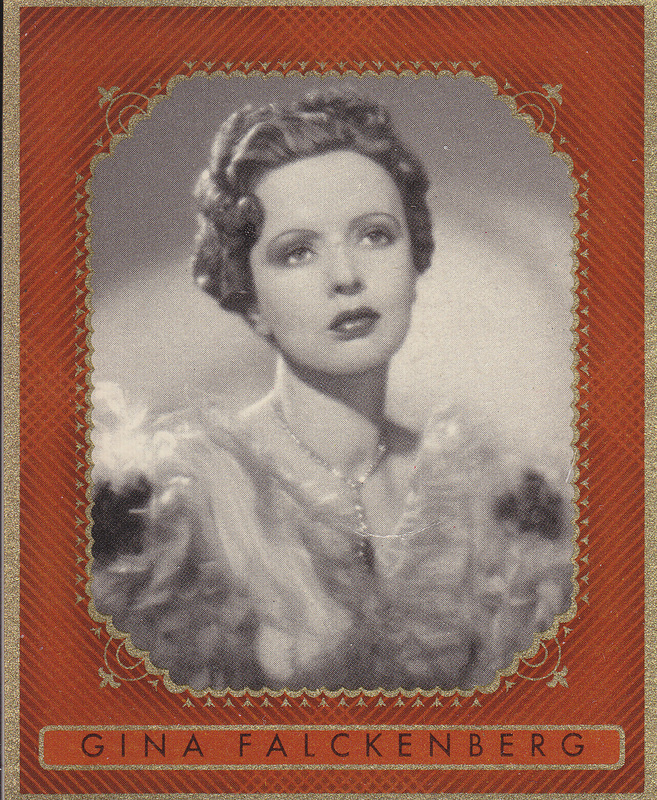

Gina Falkenberg (1907-96)

Starred with AW in Die Zigeunerbaron (1935)

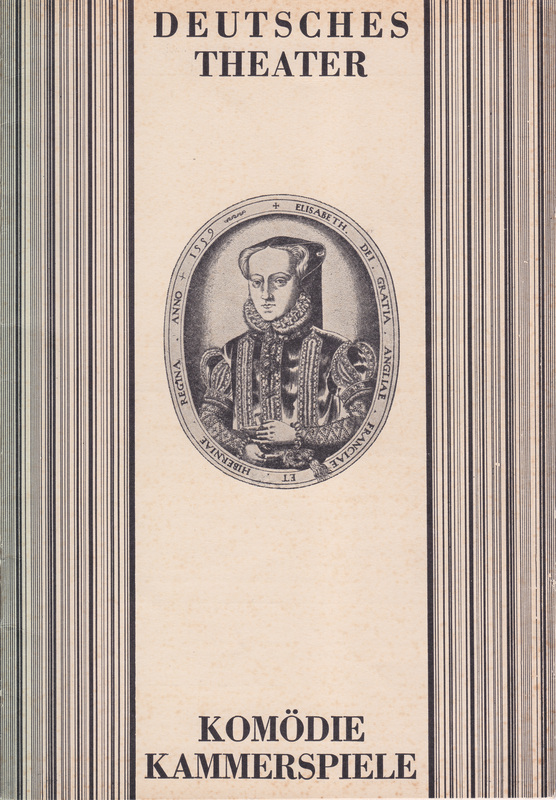

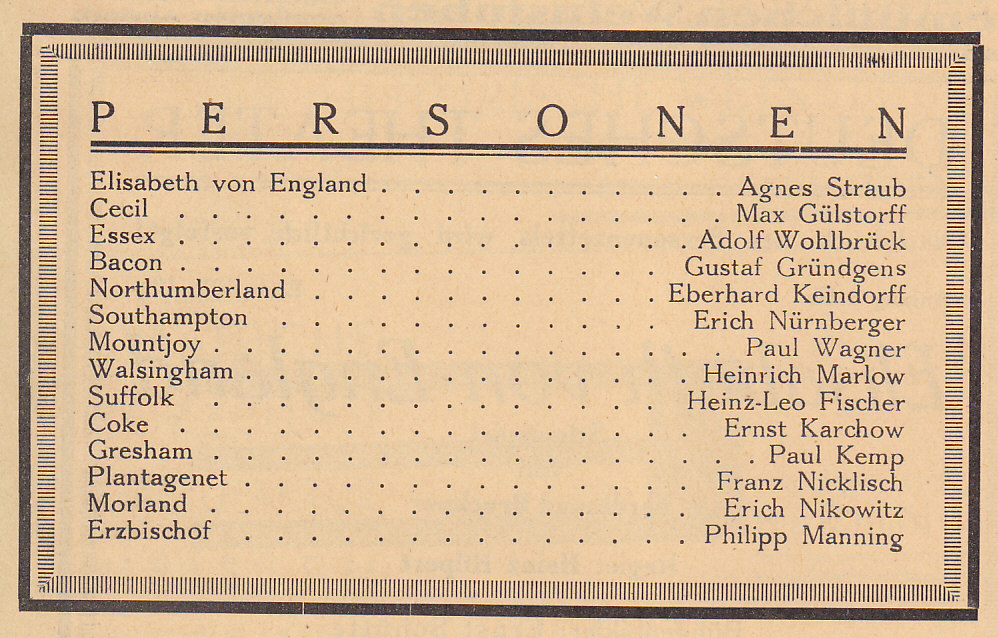

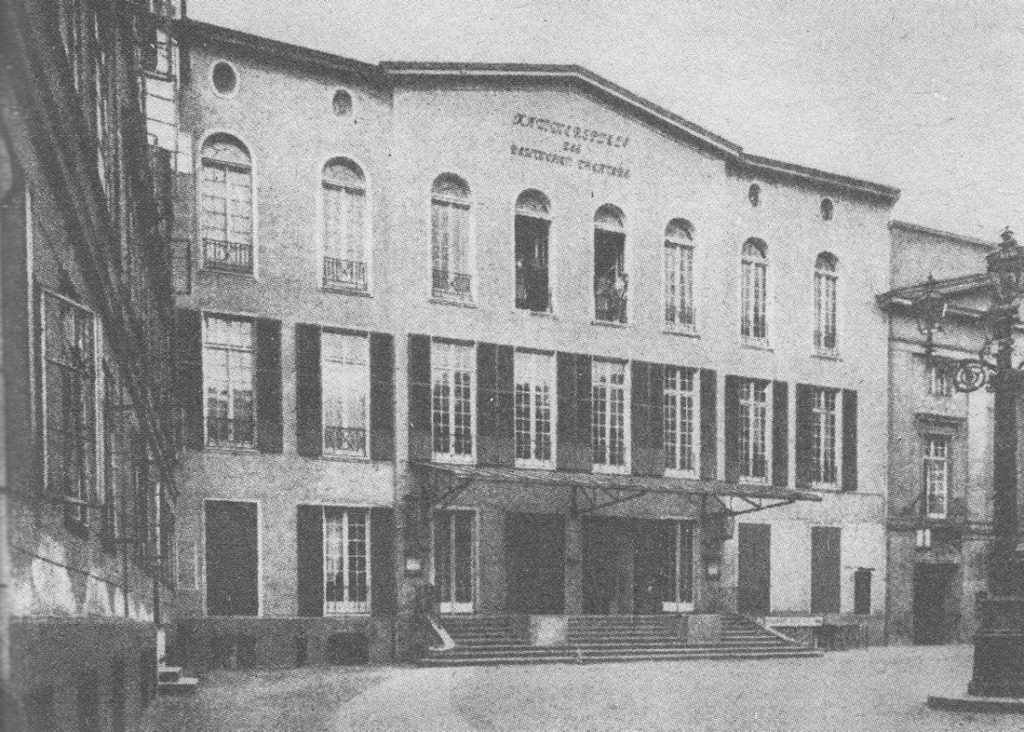

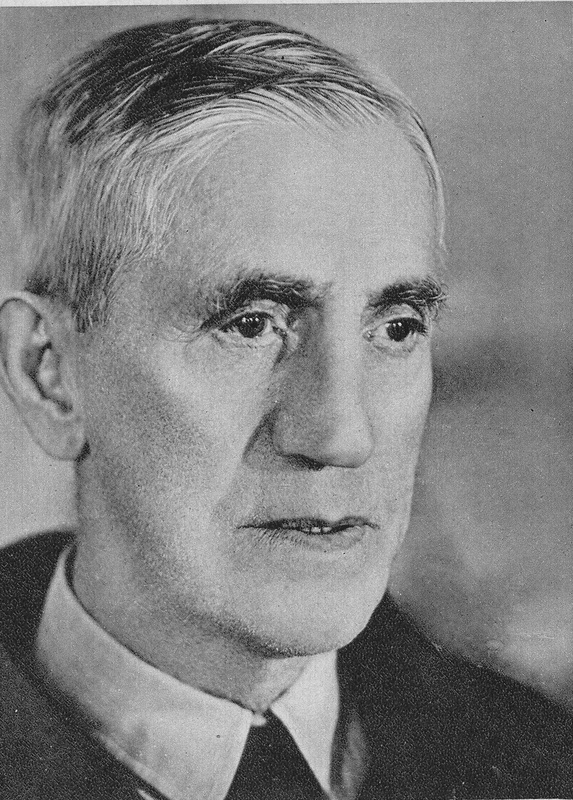

After AW returned to acting at the end of World War One, he spent four years working at the Schauspielhaus in Munich before switching to the Kammerspiele, a smaller theatre in the north Munich district of Schwabing. Since 1917 this theatre had been under the direction of Otto Falckenberg (1873-1947), a former journalist and writer. Gina was his daughter, and she had been born Anna Regina Falkenberg on 12 September 1907 in Emmering, to the west of Munich. Her mother, Wanda Kick, was Otto’s first wife.

Falckenberg had a major impact on Munich’s theatre life, earning a reputation as one of the country’s leading exponents of Expressionism. He built up a talented ensemble that included AW, Elisabeth Bergner and Heinz Rühmann. In addition to several important Shakespearean productions – including King Lear, with AW as Edmund – Falckenberg was responsible for the first staged play of Bertolt Brecht, Drums in the Night (1922) and also promoting the work of other modern writers such as August Strindberg and Frank Wedekind, in whose Spring Awakening Gina appeared following her stage debut at the Kammerspiele in 1927.

Although AW left Munich for Dresden in 1927, Gina was in her late teens when he began working for her father and it seems likely that they were acquainted. Otto Falckenburg had by this time remarried, not once but twice. In 1920 he married his second wife, actress Sybille Binder (1895-1962), but the marriage only lasted a couple of years. She moved to England in 1938 and was given supporting roles in British films, including that of Fascist agent Erna in AW’s The Man from Morocco (1945) plus another favourite of mine, Blanche Fury (1948.) Falckenburg married his third wife, Gerda Mädler, in 1924.

Gina Falckenburg followed AW to Berlin, where she began appearing on stage in 1930. She played Manuela in Christa Winsloe’s play Gestern und Heute, about the relationship between a pupil and her teacher in a Prussian girls’ school. When it was adapted for film in 1931 with the more sensational title of Mädchen in Uniform, director Leontine Sagan – another Reinhardt protege – wanted Gina to play the part of Manuela on screen as she had on stage, but was persuaded to cast Hertha Thiele instead. The teacher was played by Dorothea Wieck, the focus of AW’s desire in Der Student von Prag four years later.

Gina made her screen debut the following year, playing a prostitute in Razzia in St Pauli (1932), set in Hamburg’s red light district. By 1933 she was playing an American gangster moll – Mabel Wellington – in Der Page vom Dalmasse-Hotel, progressing to a senator’s daughter in Der Herr Senator. Die fliegende Ahnfrau (1934.) Although the part of a pig farmer’s daughter in Zigeunerbaron might appear to be a retrograde step, Arsena Zsupan cuts an elegant, almost aristocratic figure.

AW and the two Arsenas. A French language version of Zigeunerbaron was filmed simultaneously with the German one, with AW taking the lead in both films. As Falckenburg (left) spoke insufficient French, the part of Arsena in ‘Le baron tzigane’ was played by Daniela Parola (right)

Despite her initial fury at Sandor’s behaviour, Arsena soon finds herself attracted to the charismatic ‘gypsy baron’, and after she learns his real identity both she and her father realise the potential value of a marriage match…

Although Arsena can be haughty and vindictive, her character – who wears an array of fashionable costumes, jumps on horseback over pub tables, has a cat fight with Saffi and wields a whip almost as well as she fires a rifle – had more colour and liveliness than some of the other parts Falckenburg was given in the 1930s.

She married Italian film director Giulio del Torre in 1939 and moved to Italy, where she had a modest career on both stage and screen. Uniquely among AW’s leading ladies, she also found succes as a novelist and screenwriter, beginning shortly after Zigeunerbaron with Das unendliche Abenteuer (Berlin: Ullstein, 1937) and following this up with another dozen novels, plus screenplays and short stories. She died in Lucca on 12 February 1996.