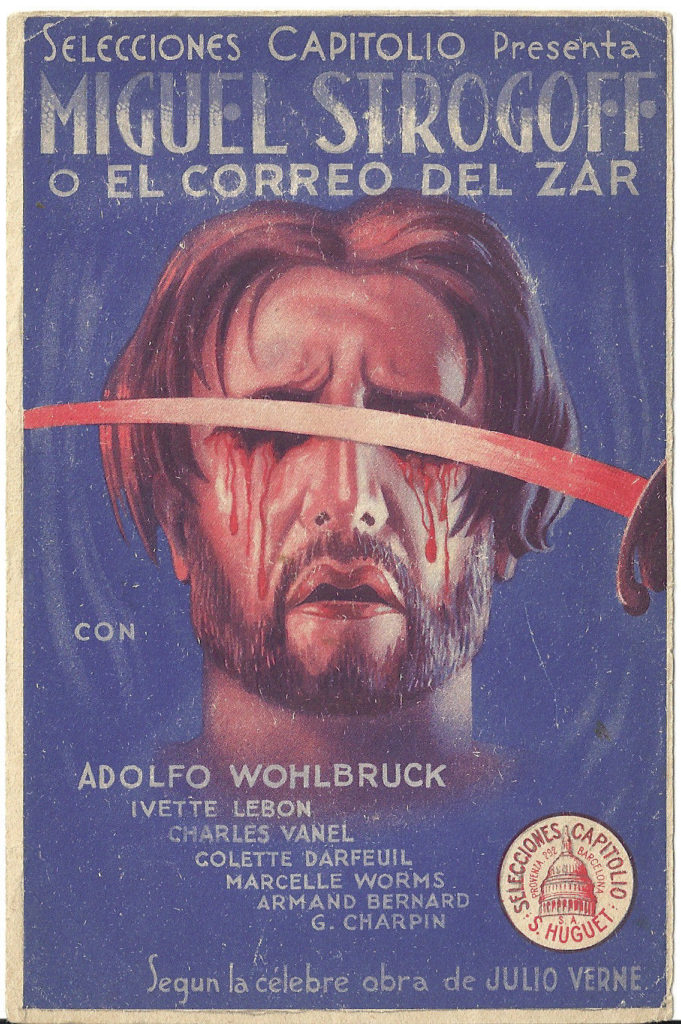

Having been rather pressed for time of late, I’ve fallen behind with various blog posts I’d planned about my AW research, as well as the ever-popular series on the actor and his ‘Leading Ladies.’ Another post on that topic should follow in the very near future, but in the meantime I am starting a new weekly series of short posts which will go up each Friday, showcasing a single item from my collection. This could be a photograph, document, lobby card, poster, vinyl record, rare book…whatever appeals to me at that moment, and these won’t appear in chronological order. This series gives me the opportunity to show some interesting images accompanied by a brief description, without the requirement to prepare much text in advance. So, to start things off, here’s a Spanish handbill advertising the French language film Michel Strogoff (Baroncelli/Eichberg, 1936) that pays grisly homage to the movie’s most notorious scene:

Birthday Note: Anton and his directors

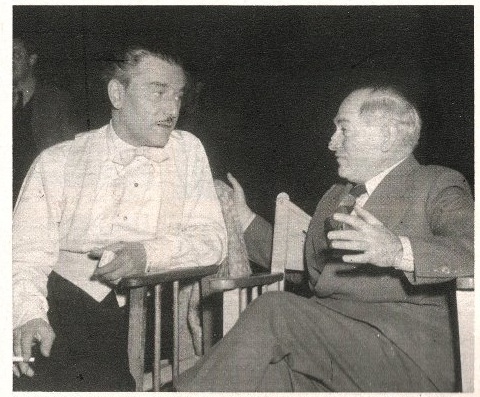

Today marks the 120th anniversary of the birth of Anton Walbrook, and to celebrate the occasion I am posting a selection of photographs that show the actor at work. During his long career, AW was privileged to collaborate with some of the most distinguished film-makers of the time, and so here are some photographs showing them together.

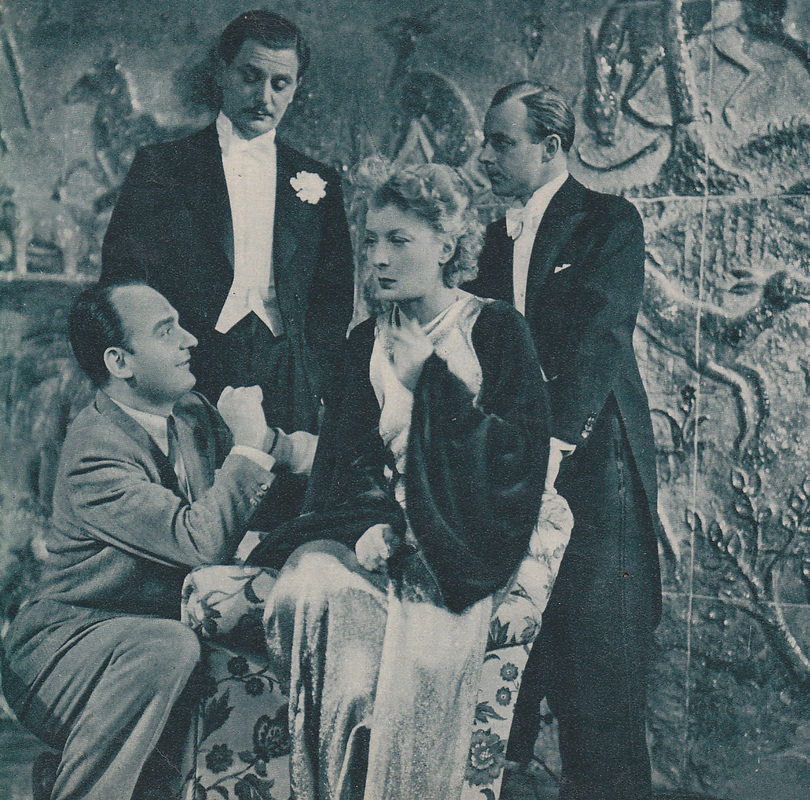

This photo shows AW, Hilde Hildebrand and Heinz Ruhmann being directed by Willi Forst, with whom AW had previously worked in Maskerade (1934.)

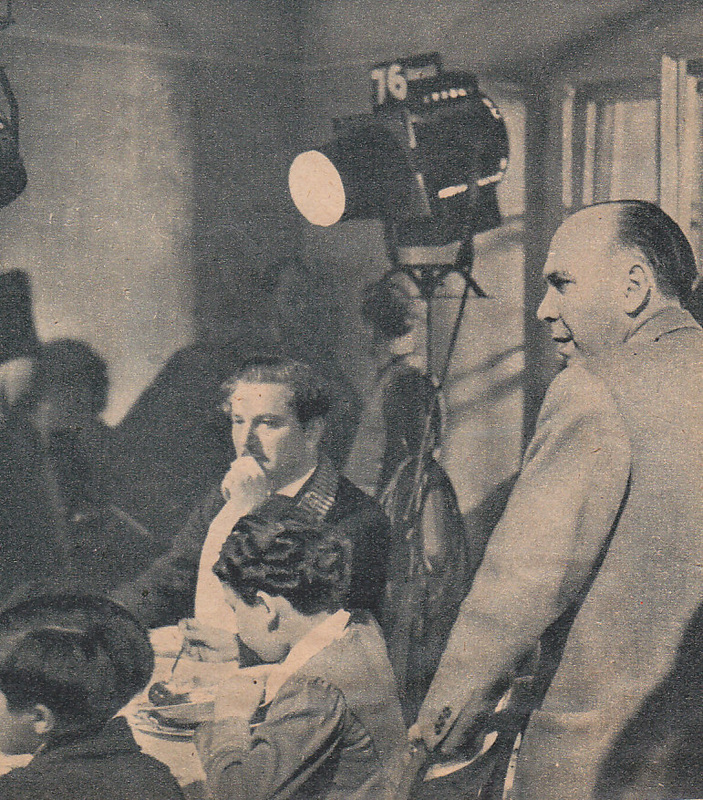

AW worked twice with Dickinson, who drew brilliant performances from him in both Gaslight (1940) and The Queen of Spades (1949). This photo also shows cinematographer Otto Heller (1896-1970) who filmed AW no less than four times. Born in Prague, he worked with fellow Czech Carl Lamac on Baby (1932) and Die vertauschte Braut (1934), in both of which AW co-starred with Lamac’s wife Anny Ondra. Port Arthur (Farkas, 1936) was filmed in Prague and was AW’s last film before leaving Nazi Germany. Heller followed him to the UK in 1940.

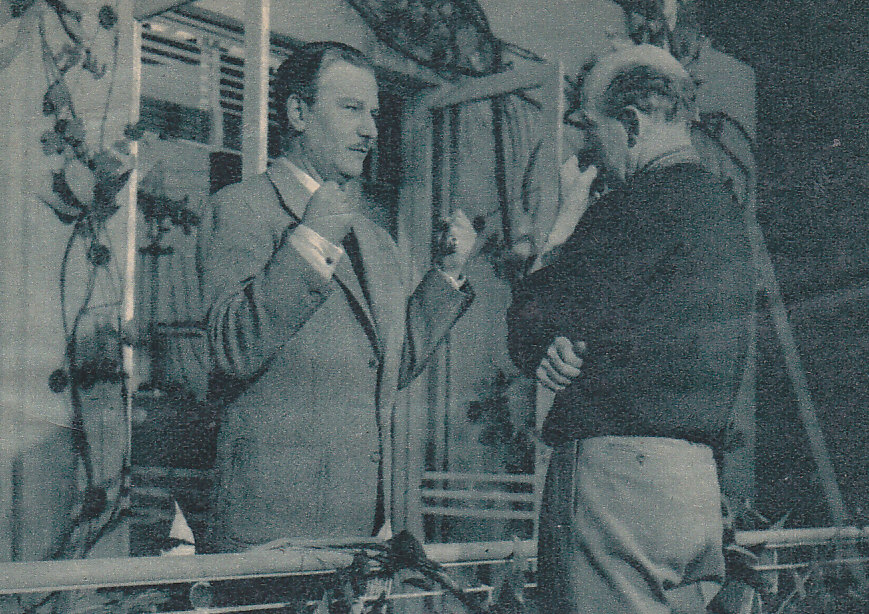

Oh, Rosalinda!! was the fourth and final of AW’s films with Powell and Pressburger, after 49th Parallel (1941), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) and The Red Shoes (1948). Many of these films shared the same cast and crew members – a reflection of the close-knit collaborative nature of Powell and Pressburger’s own creative partnership.

Heavitree’s Hispanic Corner: Richard Ford, calotypes and ‘the annals of the artists of spain’

Tucked away under a tree in the churchyard of St Michael’s, Heavitreee, by the edge of a path I once walked on a near-daily basis, lies the resting place of Richard Ford (1796-1858), Hispanicist, writer, art collector and historian. After spending several long sojourns in Spain in the early 1830s he moved to Exeter to be near his brother James Ford (1797-1877), later a Canon of Exeter Cathedral. After Richard bought Heavitree House in the summer of 1834, he filled it with books, antiques and artwork that he had brought back from Spain, and laid the gardens out using Moorish designs and artefacts.

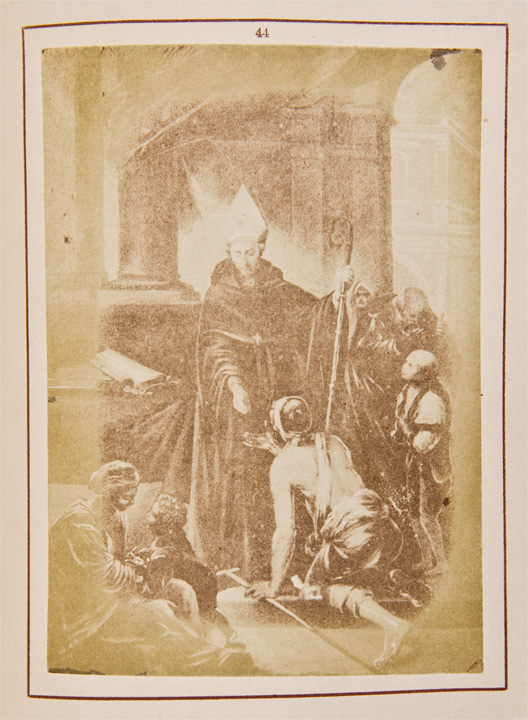

In 1840 Richard Ford met the Scottish writer and art historian Sir William Stirling (later Stirling-Maxwell, and 9th Baronet of Pollok (1818-78), who had also travelled in Spain and shared Ford’s deep interest in Spanish art and artists. The two men began corresponding on the topic. Ford’s Handbook for Travellers in Spain (1845) proved highly popular, and was reprinted in 1847, the year before Sir William’s four volume Annals of the Artists of Spain was published. This was the first scholarly history of Spanish art in English, and was chiefly responsible for making known the works of El Greco, Goya, Velazquez, Ribera and Murillo. It was, moreover, the first book on art to be illustrated with photographs. The first three volumes featured texts by Stirling Maxwell, whilst the fourth was a supplement of illustrations printed in a limited edition of 50 copies for his circle of friends and family. Sir William had taken a camera lucida on his first trip to Spain and used this as a drawing aid, but it is possible that his inspiration for using the calotype process to illustrate his book came from seeing Talbot’s Sun Pictures of Scotland (1845) or the earlier Pencil of Nature (1844.) Hill & Adamson were also commissioned to produce calotype images for the volume, but – for various reasons – their work was not included.

There were 68 photographs in all, taken by Nicholas Henneman using Talbot’s calotype process. Henneman had entered Talbot’s service in 1826 but was later trained by him as a photographer and placed in charge of the printing establishment at Reading. Many of the Spanish photographs were made from the original paintings, which had to be photographed outdoors in the sunshine due to the long exposure times required. When this was impossible, existing engravings were used. Several artworks were borrowed from Richard Ford, who died of Bright’s Disease ten years later at Heavitree House on 31 August 1858.

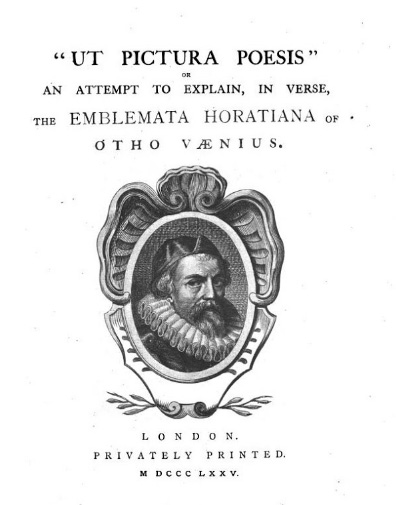

A set of the Annals of the Artists of Spain was retained at Pollok House, Sir William’s mansion in Glasgow, and a place very familiar from my childhood: in addition to regular visits to the parkland surrounding the house, my parents often went to dinner dances there, and I got to see inside the house from time to time. I still have distinct memories of seeing prints by Goya and Piranesi around the walls. When I began working in the Special Collections Department of Glasgow University Library, the Stirling Maxwell collection of emblem books became a favourite haunt, second only to the early photographic collections. Sir William’s fascination with emblem literature led him to collaborate with Richard’s brother, Canon James Ford, on the book ‘Ut Pictura poesis,’ or An attempt to explain, in verse, the Emblemata Horatiana of Otho Vaenius (London, 1875.) The preface and epigrams were written by Ford, while Stirling-Maxwell provided bibliographical notes.

The Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid is currently running an exhibition about Sir William’s volume – but Copied by the Sun/Copiado por el sol: Talbotype Illustrations to the Annals of the Artists of Spain closes tomorrow, so you’ll need to hurry if you want to catch it! Otherwise, there’s a massive catalogue published to accompany the exhibition, and the following are also well worth reading if anyone wishes to learn more:

Hilary Macartney, ‘William Stirling and the Talbotype volume of the Annals of the Artists of Spain.‘

History of Photography 30:4 (2006) pp.291-308‘The Reproduction of Spanish Art: Hill and Adamson’s calotypes and Sir William Stirling-Maxwell’s Annals of the Artists of Spain.’

Studies in Photography (2005), pp. 16-23.Gilbert, E.W. ‘

Hilary Macartney, ‘William Stirling and the Talbotype volume of the Annals of the Artists of Spain.‘

History of Photography 30:4 (2006) pp.291-308‘The Reproduction of Spanish Art: Hill and Adamson’s calotypes and Sir William Stirling-Maxwell’s Annals of the Artists of Spain.’

Studies in Photography (2005), pp. 16-23.Gilbert, E.W. ‘

Richard Ford and His Hand-Book for Travellers in Spain‘

The Geographical Journal Vol. 106, No. 3/4 (Sep-Oct 1945), pp. 144-15Radford, Cecily. ‘Richard Ford (1796-1858) and his Handbook for Travellers in Spain.’

Transactions of the Devonshire Association, Vol. 90, (1958) pp.146-166

Anton Walbrook died 49 years ago today

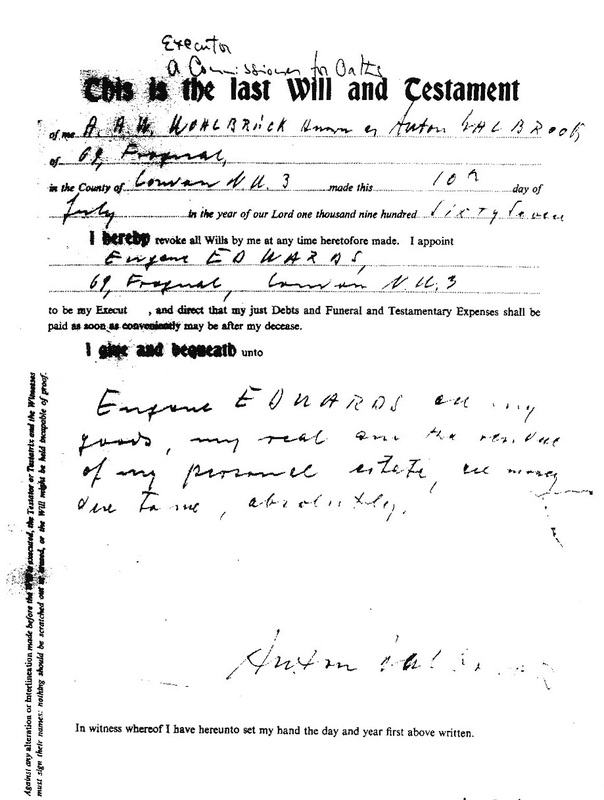

It is 49 years now since the death of Anton Walbrook, which took place at Garatshausen on this day in 1967. I have written more about his death here and here, but this year I am sharing an image of his will, which was written just four weeks earlier, on the 10th July 1967:

It was my intention that my biography – which explains more about his relationship with Eugene Edwards – would be published next August to mark the 50th anniversary of Anton’s death, but this is looking increasingly unlikely now. Hopefully the delay won’t be too long. In the meantime, may he rest in peace.

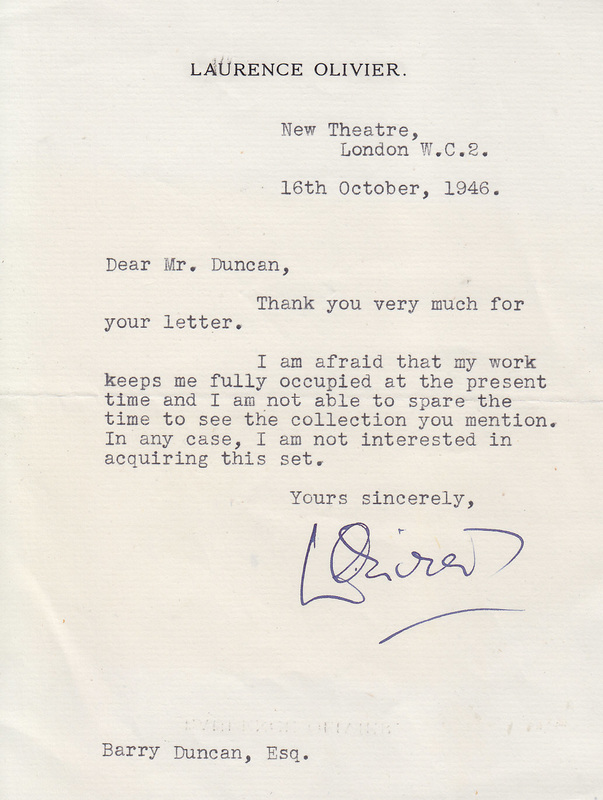

Laurence Olivier Letter

Readers of this blog may be interested to see this short and somewhat terse letter from Laurence Olivier to theatrical bookseller Barry Duncan. which recently came into my possession.

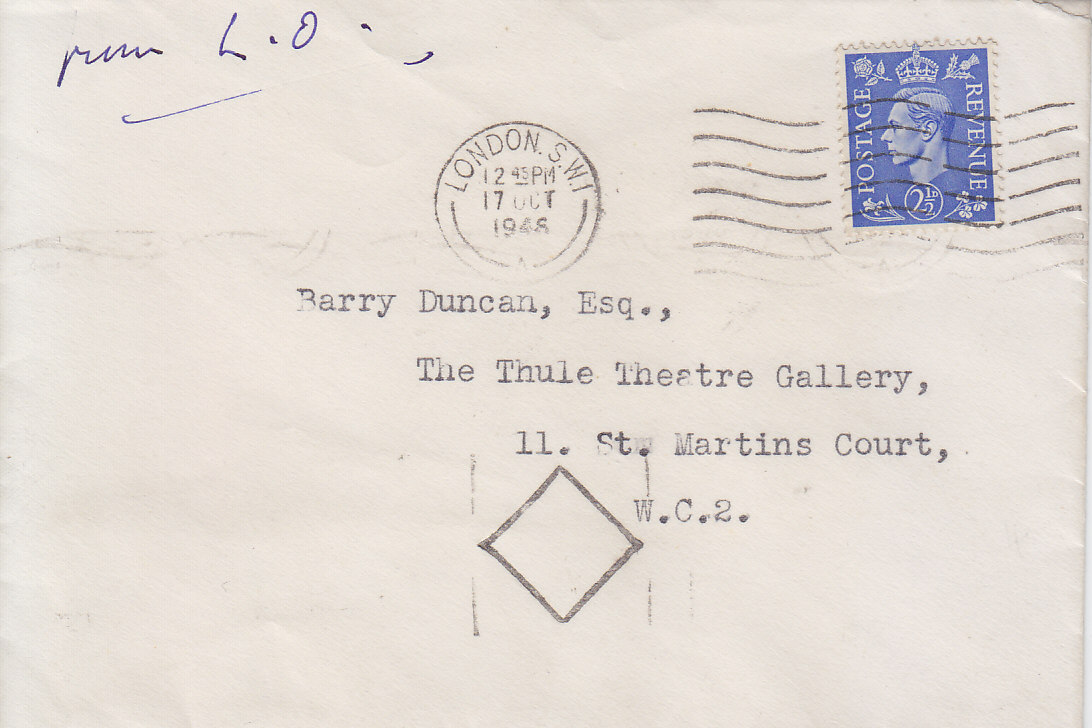

Olivier was indeed ‘fully occupied’, as he was then playing the lead role in the Old Vic production of King Lear, which he was also directing. The play was being performed at the New Theatre because the Old Vic had been damaged by bombs during the Blitz and did not reopen until 1950. The New Theatre (now renamed the Noel Coward Theatre) was almost next door to Duncan’s bookshop, although the SW1 postcode on the envelope (below) indicates that the letter was posted from elsewhere – although not the home he shared with Vivien Leigh, as Durham Cottage is situated in Chelsea’s Christchurch Street, SW3.

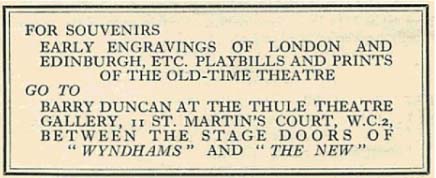

Duncan is best known now as the author of The St. James’s Theatre: its Strange & Complete History 1835–1957 (London: Barrie & Rockliff, 1964) but at this time he ran a bookselling business specialising in theatrical material and old prints.

The actor would be knighted a few months later, in May 1947. I have written about Olivier, Vivien Leigh and Anton Walbrook here, but for those wishing to read more I can strongly recommend this website.