There are many reasons to love and admire Barbara Stanwyck, not least of which is her versatility as an actress – in a film career that stretched beyond five decades she appeared in screwball comedies, melodramas, noir thrillers, musicals and westerns. Whatever the genre, she was at her best when playing a certain type of character – feisty, strong-willed women, who are prepared to think independently and defy convention when required. Megan Davis, the heroine of The Bitter Tea of General Yen, is such a person.

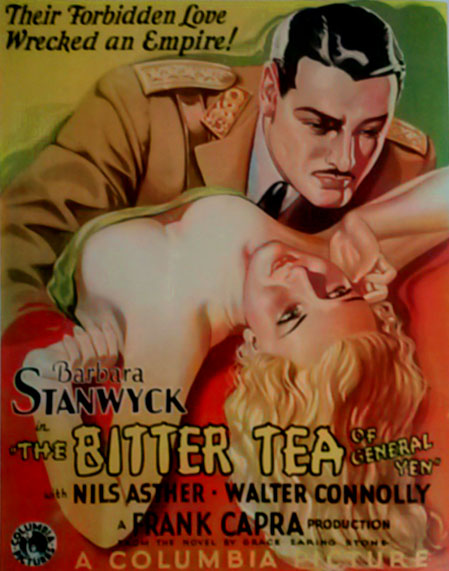

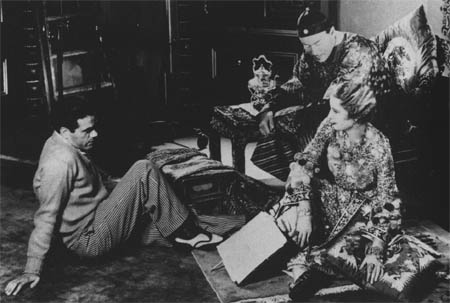

This was her fourth film with Frank Capra, who had already directed her in Ladies of Leisure (1930), Miracle Woman (1931) and Forbidden (1932.) (Their fifth and final film together, Meet John Doe, followed in 1941.) It is clear that Capra had a deep affection for the young actress, but how much she reciprocated his feelings in less certain. By the time Bitter Tea was made they were both married to other people, and it is tempting to read a poignant subtext into the film’s central theme of forbidden love. Reducing the film to this would do it a great disservice however. Capra, hoping to obtain his first Oscar, strove for high artistic standards and created a world of opulent oriental glamour, with lush sets gorgeously lit and photographed by cinematographer Joseph Walker, whose specially designed patent lenses captured Barbara’s face in radiant close-up:

Set in China during the civil war of the 1920s, the story is simple enough. Childhood sweethearts Megan Davis (Stanwyck) and Dr Robert ‘Bob’ Strike (Gavin Gordon) are engaged to be married, but haven’t seen each other for three years. Megan belongs to the ‘finest oldest Puritan family in New England’ and the film opens in Shanghai as the American mission community await her arrival, which is to be followed immediately by her wedding. They have barely had time to greet one another before news arrives of endangered orphans in nearby Chapei – and gallant Bob declares the wedding postponed as he dashes off to save the children. Megan accompanies him, but after being ‘roughly handled’ in a crowd she is knocked unconscious and wakes up on a moving troop train in the company of the notorious General Yen, played by Swedish actor Nils Asther in heavy oriental make-up.

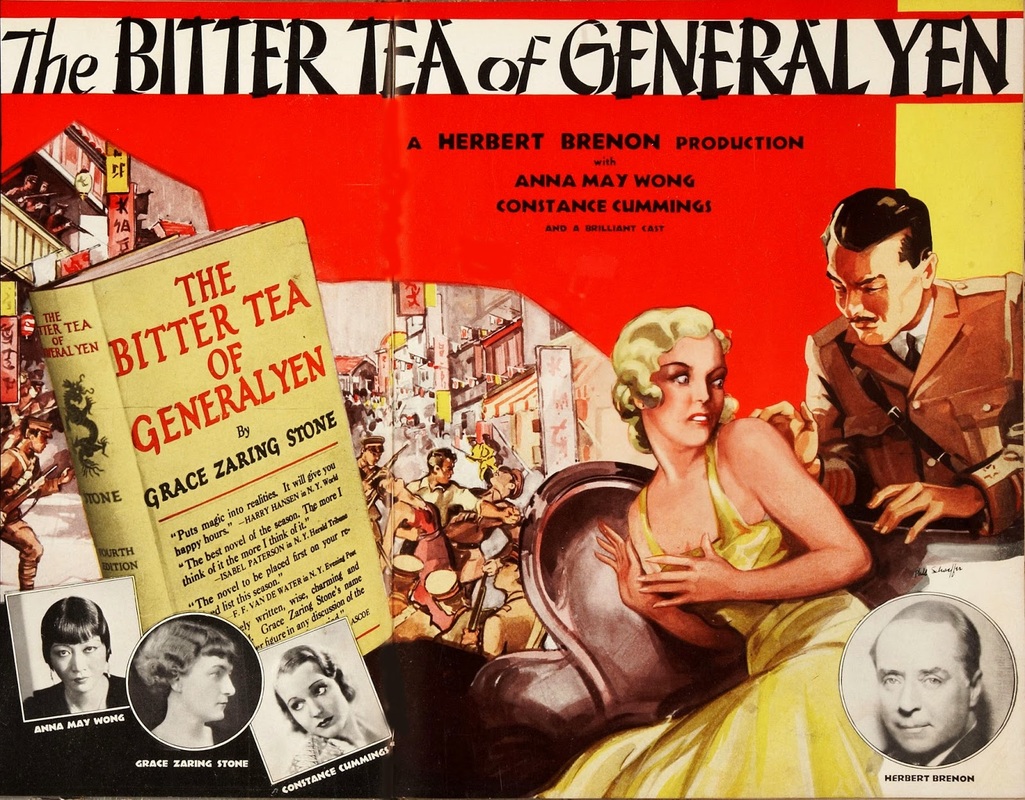

The rest of the film follows events in the general’s sumptuous palace over the next few days, a situation that is further complicated by the actions of the general’s concubine Mah-Li (played by Japanese actress Toshia Mori). Neither of the female leads was the first choice – originally, Constance Cummings played the part of Megan with Anna May Wong in the role of Mah-Li. Capra too was a late arrival: despite the fine reputation enjoyed by Herbert Brenon for silent movies such as Peter Pan (1924) and Beau Geste (1926), he couldn’t work well with Columbia executive Harry Cohn and was dropped from the film in June. The poster below shows the original line-up:

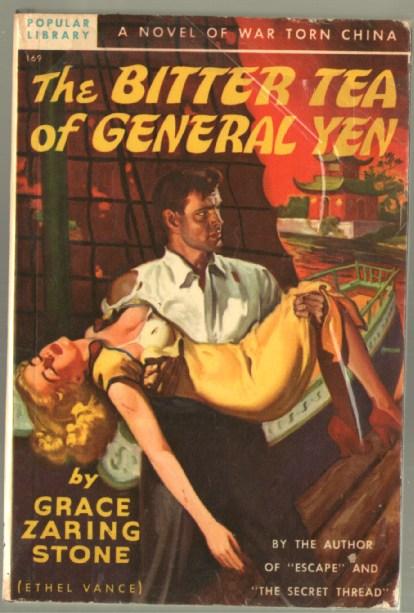

The film was based on Grace Zaring Stone’s recently published novel, which – rather like Edith Hull’s The Sheik (1919) that inspired the 1921 Rudolph Valentino movie – explored what might happen when a morally upright white woman is plunged alone into a dangerously exotic eastern setting. There was no suggestion in the book of any sentimental feelings between Megan and the general, but Hollywood must have romance, and this requirement raised the difficult issue of miscegenation which was then still illegal in many American states; it was also one of the scenarios prohibited by the Motion Picture Production Code. This being the ‘Pre-Code’ era, Capra was able to be more daring – which is not to say that no-one objected, nor that the film (in both content and production) broke free from the inherent racism of the time.

What is intriguing about Bitter Tea is the way in which it puts forward some provocative and subversive ideas at the same time as reinforcing a number of embarrassing racial stereotypes. Both consciously and unwittingly, the film raises a series of fascinating questions about the clash of civilizations, cultural superiority, racial stereotypes, sexual politics, gender and power.

Over the space of the next few days and nights Megan and Yen engage one another in a battle that is both cultural and personal, spiritual and sexual. While Megan seeks to preach the gospel of forgiveness and mercy to the general, he rises to the challenge and announces that he will ‘convert the missionary’ to his own philosophy. Stanwyck captures the gradual shift in Megan’s attitude, as haughty defiance and courageous pleading give way to doubt about her own beliefs and emotions, and – finally – the revelation of her innermost feelings. It might not rank among her very best roles, but her performance here is curiously overlooked and – arguably – underrated. Megan may be a missionary but she’s no angel, and Stanwyck’s reputation as a strong personality gives her character’s inner conflict a believable depth that might not have been portrayed so effectively by the other actresses considered for the part.

The reality of this inner conflict is depicted most memorably in a remarkable dream sequence. Megan dozes off in her chair after enjoying a cigarette out on the balcony, where she has been watching soldiers and girls kissing and flirting in the gardens below. The frame dissolves into a montage of superimposed images – the ‘cherry moon’, rippling water – as she drifts into sleep to the sound of soft pipe music. The mood is shattered as a threatening figure smashes down the door and forces his way into her bedroom – it is a diabolical version of Yen, resembling an oriental Nosferatu with pointed ears, fang-like teeth and nails as long as talons. Just as he forces her down on the bed and runs his hands over her breast, she is rescued by a masked hero in western dress who pulls off his mask to reveal….General Yen. As is the way with dreams, she registers no surprise at the conundrum, but kisses him passionately. It’s an extraordinary sequence, made even more unforgettable by the skewed camera angles and the sight of General Yen floating backwards – an effect achieved by mounting him on a dolly. It’s brilliantly effective, both visually and psychologically, offering a highly expressive insight into Megan’s subconscious desires.

Her wavering between attraction and repulsion hinges, at least partly, on the racial barrier that separates them, and there is no shortage of orientalist stereotypes in the film: China is shown as a place of chaos, sensuality and cruelty, where human life is cheap and everyone conceals their inner selves behind masks of ‘inscrutability.’ Yet western culture is far from idealised. The American missionaries are shown from the outset to have little understanding of, or sympathy with, the Chinese society in which they live. Apart from Megan the most prominent western character is General Yen’s financial adviser Jones (Walter Connolly), a cynical and mercenary individual, a self-confessed ‘renegade’ who is indifferent to killings all around him as long as he makes money for (and from) his employer.

When General Yen asks Megan if she has ever read Chinese poetry, listened to his culture’s music or studied their painting, her silence proves his point. Jones slyly points out to Megan that the treacherous Mah-Li was raised in a mission school, effectively undermining the value of the work done by the likes of Dr Strike. The ruthlessness of General Yen has its own logic too: in response to Megan’s protest about shooting prisoners for whom they have no food, he asks her ‘Isn’t it better to shoot them quickly than to let them starve slowly?’ Sunday School has not prepared her for this. She has no answer. Inch by inch, all certainties about the superiority of her culture and religion are taken away.

Despite her education and social status, Megan is clearly no match for Yen in theological debate, and indeed the film seems to support his accusation that her fine-sounding words are false. When she urges him to change his mind about Mah-Li she ends with a heartfelt appeal: ‘I promise you, for the first time in your life you’ll know what real happiness is.’ His decision to do what she asks leads instead to his downfall – a result that he accepts with Stoic equanimity. Megan, by contrast, is shown to be totally out of her depth, in a complex world she does not understand; her well-meaning but misguided actions will result in the deaths of those she sought to save.

As a final indictment of Megan’s Christianity, the document that betrays Yen is disguised as a prayer for forgiveness – her ignorance of Chinese script means that she is blind to the true meaning of the words.

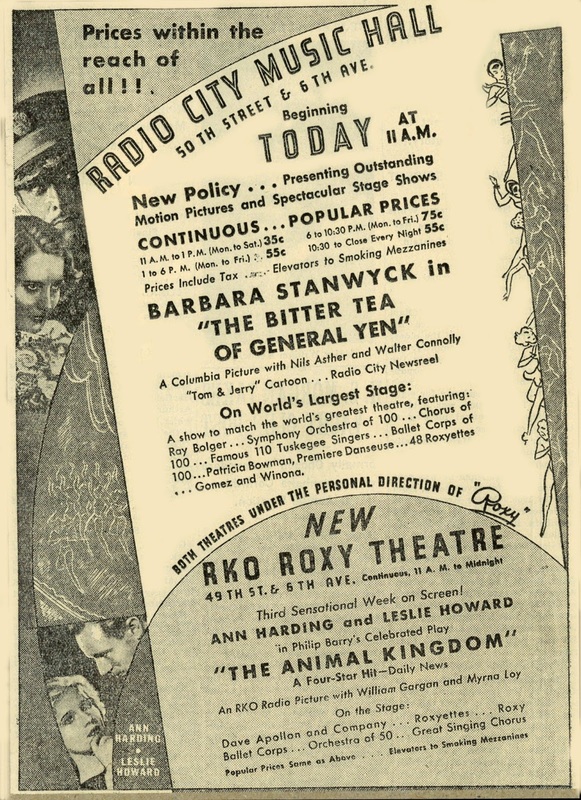

This incident mirrors an earlier one when Bob Strike’s inability to read the same script meant that he believed General Yen’s mocking message was actually a pass guaranteeing safe conduct for him and Megan. There are several such recurring motifs in this carefully-crafted movie, which was filmed in the summer of 1932 and cost around $1 million to make. The Bitter Tea of General Yen was Columbia’s most expensive film to date. The studio was uneasy about its prospects, however, sensing that the taboo subject matter could prove problematic. Its planned opening date of 20 December was postponed until 11 January 1933, when it was screened at the revamped Radio City Music Hall in New York:

This was the first ever movie to play at the vast hall, which had opened as a high class venue for vaudeville entertainment two weeks earlier. Unfortunately this was the at the height (or rather low point) of the Depression, and few could afford the $2.50 tickets. Poor attendances forced the owners to hastily reconstitute the building as a movie picture palace, and for their prestigious re-opening they paid $100,000 to rent Capra’s new film. It was scheduled to run for two weeks, but disappointing box office returns led the owners to pull the picture after only eight days, leaving them with a loss of over $20,000. Both Stanwyck and Capra later expressed their belief that the film’s poor reception was due to racist attitudes, not just in America but in Britain and other Commonwealth countries. A cursory skim through contemporary reviews suggests they were correct.

What can the film offer to modern audiences? To be fair, the use of ‘yellowface’ make-up and negative Chinese stereotypes is bound to jar with many contemporary viewers, but hopefully this should not distract from the sincere efforts made to challenge prejudices about the taboo of interracial romance. Despite its mixed messages, there is no denying the visual pleasure to be found in watching The Bitter Tea of General Yen: thanks to the designs of art director Steven Goosson, Joe Walker’s camera work and the costumes of Edward Stevenson and Robert Kalloch, the film looks stunning. Few things in Capra’s later work compare with the beautifully-lit, opulent interiors of General Yen’s palace, the carefully-orchestrated crowd scenes and the feverish expressionism of that erotic dream. Capra succeeded in making the arty-looking film he wanted, even if it failed to bring him his much-coveted Academy Award. He’d have to wait another two years for that.

As for Stanwyck, well she could make any film worth watching, raising even the most humdrum storyline up by the sheer vitality of her performance, and The Bitter Tea of General Yen gives her a great deal of material to work with. Her opening scenes are rather weak, perhaps because she couldn’t quite square with the notion of Megan as the girlishly eager young saint the script desired. Once Yen appears onscreen, she grows into character, responding powerfully both to the general’s words and to her own conflicting feelings. Watching her face after she awakes from that dream, it is possible to see her expressions capture successively the subtle, intoxicating ripples of shock, guilt, pleasure and confusion as she remembers what has passed through her mind. Although not as provocative as Babyface, the daring sensuality of Bitter Tea would be impossible to screen after strict enforcement of the Code began the following year. In more ways than one, the film is a prisoner of its age; but no imprisoned missionary ever looked more radiant or alluring than Barbara Stanwyck does here.