With her imperious personality and feisty nature, one might argue that no actress was more suited to playing a monarch than Bette Davis. It’s therefore unsurprising that she played Queen Elizabeth (the First) not once but twice – a distinction shared only with Glenda Jackson, who reprised the role twice in 1971. Sixteen years, however, had passed between The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (Michael Curtiz, 1939) and The Virgin Queen (Henry Koster, 1955), and the superiority of her performance in the latter film surely owe more than a little to the difficulties endured by Bette during this period.

The two films were very different anyway. The 1939 movie was based on the

play by Maxwell Anderson and focused on the queen’s relationship with Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex – the character played by Anton Walbrook in

Elisabeth von England and discussed

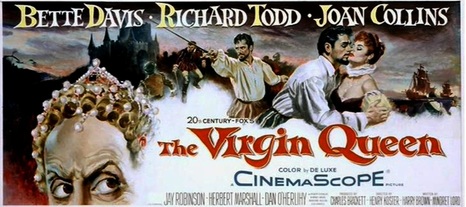

here. This time her romantic interest is Devon-born Sir Walter Raleigh, played by Richard Todd. Beginning in 1581 after Raleigh’s return from fighting in Ireland, the film follows his arrival at the queen’s court – achieved through an old family connection with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester (played by Herbert Marshall, who had starred opposite Bette in

The Letter (1940) and

The Little Foxes (1941) both directed by William Wyler.) Standing apart from the obsequious etiquette of other courtiers and royal confidantes with his direct speech and soldier’s boldness, Raleigh quickly attracts the queen’s attention. A distinguished career at the court seems assured, but Raleigh’s only wish is to sail Her Majesty’s ships on an expedition to the New World, and for this he needs her support. For Raleigh, serving the queen loyally is a means to this end. But for her? – the rest of the film explores the question of what Elizabeth sees in him, and how their conflicting interests and desires affect their relationship.

As this outline suggests, this story is really about Raleigh, not Elizabeth. In fact, the original treatment for the film was entitled Sir Walter Raleigh and was intended as a vehicle for Richard Todd. It had been over two years since Bette Davis last made a film, and Darryl Zanuck knew he could only lure her over to his studio, 20th Century Fox, with a juicy part. The Raleigh script was therefore substantially revised by screenwriters Harry Brown and Mindret Lord to give Queen Elizabeth a much more prominent role. This was almost the reverse of what happened in 1939, when the star status of Errol Flynn forced the insertion of his character’s name in the title. Todd was no Flynn, however, and both his character and his performance were totally eclipsed by Davis’s portrayal of the queen. Although Todd’s character is more aggressive than the Earl of Essex, no-one could buckle a swash like Errol Flynn, and Raleigh never really captures the same level of charismatic charm.

The Virgin Queen was filmed in CinemaScope, a relatively new widescreen technology that was well-suited to sumptuous costume dramas. It was directed by Henry Koster, who had shot the first CinemaScope film – The Robe – in 1953, and has also just finished working with Richard Todd in A Man Called Peter (1954.) As the pictures (above and below) demonstrate, the CinemaScope format captures a wide panoramic sweep of detail, which in turn placed particular demands on the actors: they had to enter and exit scenes neatly, and remain in character even at the edges of the action.

The queen’s rival in love: Lady Beth Throgmorton (Joan Collins)

There was at least one point that made the role easier for Bette. The Private Lives had followed the queen right to the end of her reign, meaning that the 31-year-old actress had to play a woman almost twice her age. When filming for The Virgin Queen began in February 1955, she was 47, much closer in age to the real queen during this period – the film ends almost a decade earlier with Raleigh’s departure for South America. Not only was Bette freed from the temptation to make strained efforts to capture the physical effects of old age, but her experiences during the last sixteen years meant that she was able to bring greater empathy to the role of the ageing monarch. This is a more subdued Elizabeth than that of The Private Lives – even the most ferocious outbursts are underscored by a vulnerability that brings poignancy and depth to her character. This is particularly evident in her dealings with one of her ladies-in-waiting – Lady Beth Throgmorton (played by a young Joan Collins), whose romance with Raleigh causes the queen pangs of jealousy. When she reveals her feelings about age, beauty and fertility, the audience realises that her harsh reactions may not be quite as superficial and petulant as first appear.

The costume designer, Mary Wills, was nominated for an Academy Award.

Despite this sense of inner empathy between actress and character, Davis in no way shrank from physically portraying the queen’s age. Ten years earlier in The Corn is Green (Rapper, 1945) she went against advice and insisted on making herself look older and dowdier than was required for the part. For The Virgin Queen, she went even further. Although many other distinguished actresses have played Elizabeth I – it’s a role that has attracted those of the calibre of Sarah Bernhardt, Glenda Jackson, Vanessa Redgrave, Judi Dench and Cate Blanchett – only Bette Davis went to the lengths of having her hair shaved. Although this might have deterred lesser souls from appearing in public – far less acting as a presenter at the Academy Award ceremonies – Bette dressed in a pseudo-Elizabethan costume and headpiece to present Marlon Brando with the Best Actor award at the Oscars on 30 March 1955.

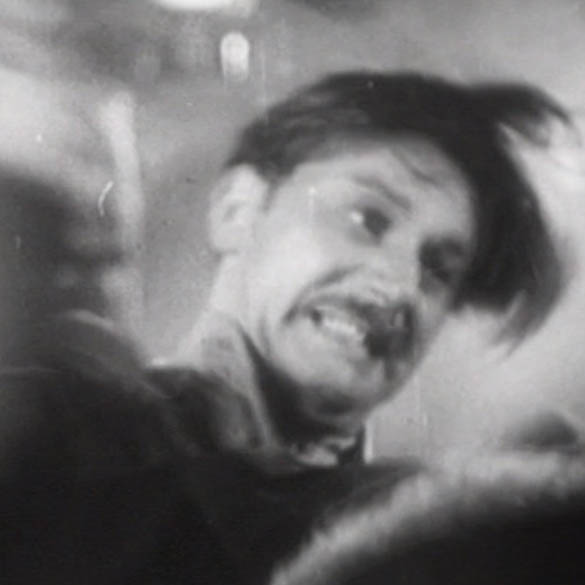

Bette Davis after presenting Marlon Brando with his Academy Award for ‘On the Waterfront’, alongside Grace Kelly with her Oscar for ‘The Country Girl.’

She may have once referred to herself as ‘the Marlon Brando of my generation’ but Bette certainly did not share the actor’s reputation for mumbling, and her acerbic delivery of some of the film’s witty rejoinders still zing and sparkle, even if her accent is a curious blend of mock-Cockney and her natural clipped New England tones. There are numerous other historical oddities and anachronisms in the film, from the jumbled chronology to the presence of telescopes and the name of Raleigh’s ship. The underlying negativity about powerful women could also be classed as a ‘historical oddity’, reflecting as it does more than a little of the gender stereotypes of the 1950s – which is not to say that some contemporary opinions expressed on women’s roles seem even less enlightened than those of the Elizabethan era.

Bette Davis eyes….

At Bette’s request The Virgin Queen received its premiere in Maine, preceded by a cocktail party at her home, Witchway. Thousands of people crowded the streets outside the Strand Theatre in Portland, Maine, for the screening on 22 July 1955. It was not the huge success that Zanuck had hoped for, however, and less than overwhelming box office returns were not helped by the studio’s overly-pessimistic approach to publicity. Although colourful and adorned with magnificent costumes, audiences found parts of the film too stagey and dialogue-heavy. Overall, it is perhaps fair to say that it lacks the sparkle and visual spectacle possessed by The Private Lives, but the fearless and regal performance of Bette Davis is essential viewing: in the hands of a lesser actress, this version of Elizabeth could have been a comic monstrosity.

The film’s legacy has also proved enduring. Discernible borrowings can be traced back to The Virgin Queen from most subsequent Elizabethan biopics, whether in the films themselves or the promotional imagery. Joan Collins revealed that much of the imperious bitchiness she brought to her role thirty years later as Alexis in Dynasty had been learned from Davis during the filming of The Virgin Queen, while Bette’s striking make-up provided the template for Helena Bonham Carter’s appearance as the Red Queen in Alice in Wonderland (Burton, 2010.) This royal performance continues to cast a long shadow.

For those interested in reading more about this and other film portrayals of royalty, I can recommend the newly-published collection edited by Mandy Merck, The British Monarchy on Screen (Manchester University Press, 2016) which includes no less than three essays on Elizabeth I as well as my own contribution on Anton Walbrook’s portrayal of Prince Albert.

This was written as part of The Bette Davis Blogathon and there are a whole host of wonderful posts available to check out there.