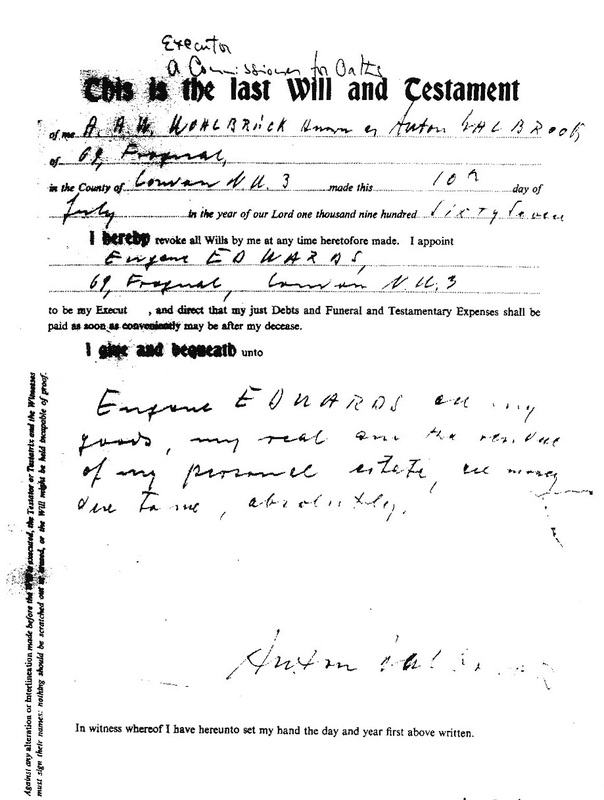

Category Archives: Anton Walbrook

Walbrook’s Leading Ladies: Part Four – Lil Dagover

Starred with AW in Eine Frau die Weiss Was Sie Will (Victor Janson, 1934)

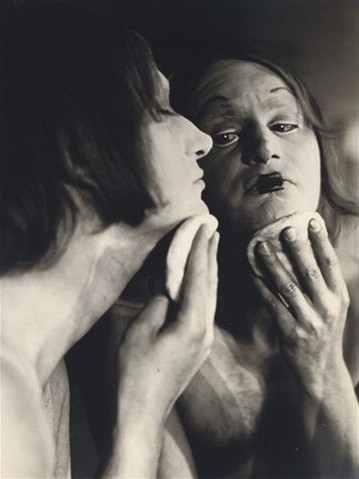

Her striking looks inspired Max Reinhardt to have her personify ‘Beauty’ at his new festival in Salzburg in 1925, a role she reprised for the next six years. Unlike many other silent actresses, she survived the transition to sound, and her acting skill probably benefited from her brief visit to Hollywood in 1931 to star in The Woman from Monte Carlo. She certainly appears more lively and natural in her performances after she returned to Germany, and this too is noticeable in her co-starring role with AW.

As it’s based on an operetta by Oscar Strauss, Eine Frau die weiss was sie will (Viktor Janson, 1934) has both a musical plot and plenty of musical numbers. Lil Dagover plays Mona Cavallini, an opera star who is much admired by the men, especially the debonair Axel Basse (AW, of course.) Unfortunately, he also has an admirer – the lovely young Karin (Maria Beling), daughter of stern industrialist Erik Mattisson (Anton Edthofer.) Entirely smitten with Anton (well, who wouldn’t be?), and frustrated at his infatuation with the opera singer, Karin asks her father to arrange for a meeting with Cavallini so that she can explain about her feelings. Her plan is successful – Cavallini spurns Axel’s advances and instead sends him in Karin’s direction, resulting in their marriage.

What Karin doesn’t know is that Cavallini is actually her mother, who left her husband and infant child many years earlier for a career in showbusiness and has been prevented by Mattisson from ever having contact with her daughter as a result. Matters become complicated when Karin learns that her husband has met Cavallini behind her back. Upset at the thought that he’s having an affair, she decides to get her revenge by having a fling with another man. Cavallini learns of her plan – but can she stop her daughter destroying her marriage? Will she reveal her identity to Karin? Things are resolved, as one would expect, with a great deal of light-hearted melodrama and singing.

A talented singer as well as actress, she did her own dubbing in foreign languages for multi-lingual releases, and worked with many of AW’s peers, such as Reinhold Schunzel for whom she played London fashion queen Jennifer Lawrence in Das Mädchen Irene (1936.) She was honoured as a Staatscchauspielerein (State Actress) by Goebbels for her role as the adultress Yelaina in Die Kreutzersonate (1937). and enjoyed a successful film career that continued throughout the post-war era and – like AW – led her onto German television in the 1960s.

Shakespeare 400

Bear essentials

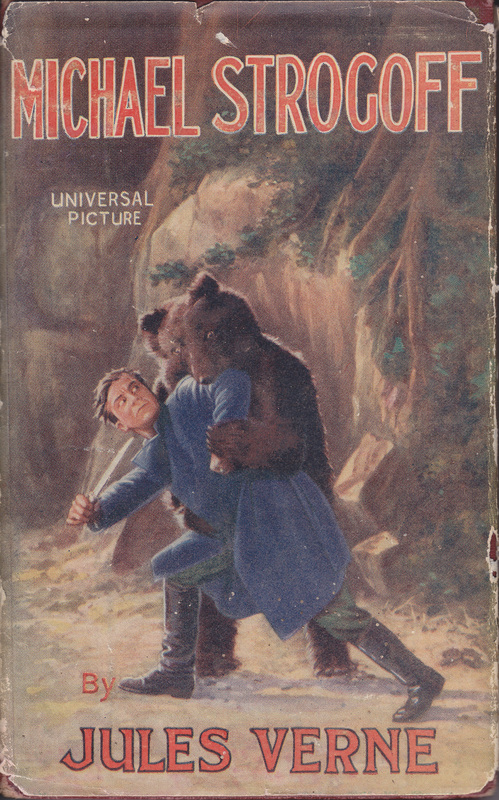

Jules Verne’s novel Michael Strogoff: the Courier of the Csar was first published in 1876 and is regarded as one of his finest works. It is a stirring tale, concerning the adventures of Michael Strogoff, who acts as courier for Tsar Alexander II and has to dash across Siberia to warn the Tsar’s brother – governor of Irkutsk – of planned treachery by a local Tartar warlord named Ivan Ogareff. Strogoff encounters various characters on his journey – Nadia, daughter of a political exile, two journalists reporting the war – as well as his mother in Omsk, where he is captured while visiting. Nadia and Strogoff’s mother are forced to watch as Michael is (apparently) blinded with a hot blade by the cruel Tartars, but he later escapes and reaches Irkutsk where Nadia’s father helps defeat the rebellion, before giving Strogoff his daughter’s hand in marriage.

The novel was adapted for the silent screen in 1926, with Ivan Mozzhukhin in the title role – the same actor also played Hermann in an early silent version of The Queen of Spades (Protazanov, 1916), endowing him with the rare distinction of prefiguring AW’s roles in two films. In 1935, although less than ten years had passed since Tourjansky’s movie, it was decided that the time was ripe for a remake (as I said above, nothing is new in the movies!), taking advantage of the advent of sound and improved technology.

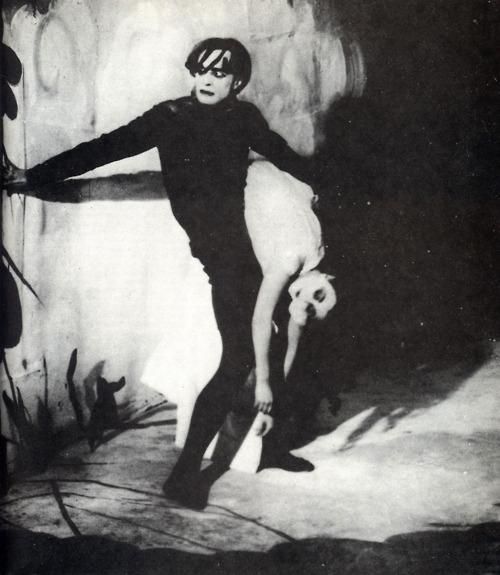

I’ve written elsewhere about certain scenes in the film where AW’s posture evokes the iconography of Saint Sebastian but here I want to focus on his fight with the bear. As readers of this blog are probably aware, the actor was actually a great animal lover, and I’ve collected together a number of postcards and images celebrating this here. The scene perhaps jars less with the actor’s personal attitude when it is understood that Strogoff kills the animal while defending a helpless woman who has fainted in fright at the bear’s feet.

In the novel, the incident occurs in Part I, Chapter XI (pp.76-77 in my copy of the film tie-in shown above) and differs considerably from the screen versions. Here, Strogoff and Nadia are travelling through the forest in the company of the two journalists when ‘a monstrous bears’ bursts out the trees and attacks their horses. Nadia tries to defend the horses with her gun, but Strogoff leaps between her and the animal, knife in hand, and swiftly despatches the bear, executing ‘in splendid style the famous blow of the Siberian hunters.’

In the film Der Kurier des Zaren (Eichberg, 1935), the bear attack takes place on board a ship. Strogoff and Nadia (Maria Andergast) are among many passengers watching a group of gypsies on deck, one of whom is goading a ‘tame’ bear to perform tricks for their entertainment. The animal is startled by the magnesium flash on the journalists’ camera, attacks its trainer and breaks free. Strogoff runs forward to save an elegantly-dressed lady (Hilde Hildebrand) who has collapsed in fright, little knowing that she is in fact Zangara, the lover of Ogareff, who will later betray him.

The British Monarchy on Screen (2)

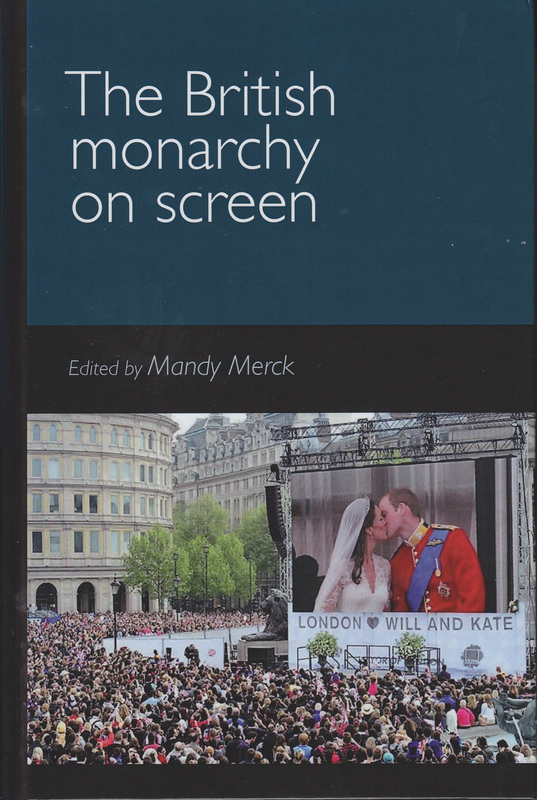

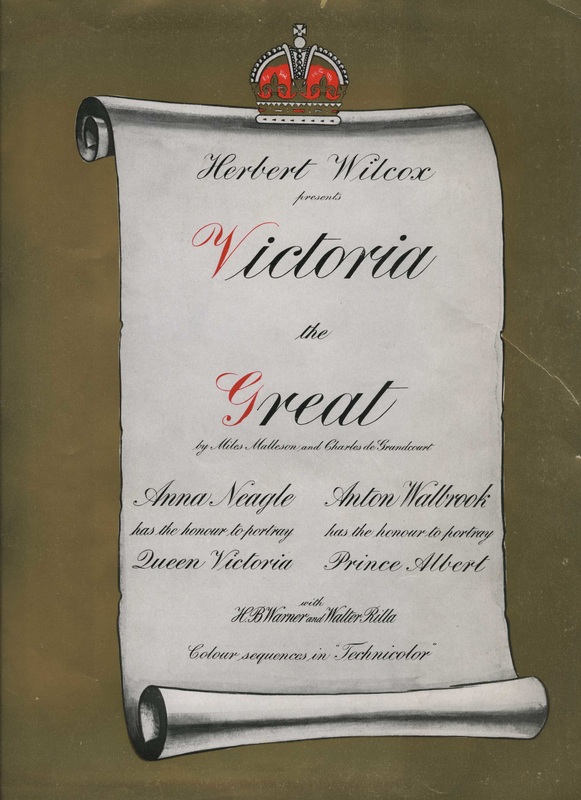

The first thing to strike the eye is, of course, the change of cover picture, and I must confess to feeling a stab of disappointment in seeing that Anton was no longer on the cover, unlike in the the original proposed version (right.) This photograph of AW and Anna Neagle together in Victoria the Great does however appear within my chapter along with another still from that film showing AW seated at the piano surrounded by young ladies of the royal court. Mine was not the only paper to look at Wilcox’s films, and Professor Steven Fielding’s ‘Heart of a Heartless World: Screening Victoria’ discusses the political aspects of the films in comparison with other screen portrayals of the queen.

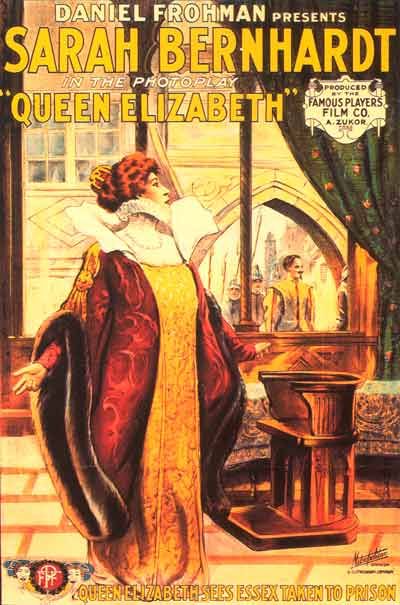

Despite inevitable overlaps like the above, an impressively diverse range of films and television programmes come under scrutiny, beginning with Victoria’s early involvement with photography and her depiction in silent cinema – such as the lost Sixty Years a Queen (Barker & Samuelson, 1913) and Queen Elisabeth (Desfontaines & Mercanton, 1912) starring Sarah Bernhardt (below.)

Moving beyond Sarah Bernhardt’s performance, cinematic portrayals of Elizabeth I proved a popular subject for examination. One paper was devoted to Quentin Crisp’s casting in the role in Orlando (Sally Potter, 1993) while another cast a critical eye over a series of film interpretations – Flora Robson in Fire Over England (Korda,1937), Bette Davis in The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (Curtiz, 1939) and The Virgin Queen (Koster, 1955), Jean Simmons in Young Bess (Sidney, 1953), Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth (Kapur, 1998) and its sequel Elizabeth: the Golden Age (Kapur, 2007) as well as Judi Dench in Shakespeare in Love (Madden, 1998) – for which she won an Oscar, despite only being onscreen for about eight minutes.

Her award reflects something of the iconic prestige that is attached to screen portrayals of royalty – an association that received extensive, and sometimes critical, attention during the conference. One key theme was the way in which both the monarchy and film-makers exploit each other to further their own interests- The Queen (Frears, 2006), for example, was described by David Thomson as ‘the most sophisticated public relations boost HRH had had in twenty years’, while directors such as Herbert Wilcox were equally adept at endowing their promotional materials with symbols of regal status: